The Almond Blossom Appreciation Society (25 page)

Read The Almond Blossom Appreciation Society Online

Authors: Chris Stewart

T

EN SACKS OF SHEEP MIX,

one of barley and one of wheat for the chickens, some horse mix, and a bag each of biscuits for the dogs and cats. I looked at the great weight groaning in the back of the car and, satisfied with my agricultural credentials, slammed the back door in a cloud of dust. A big white van had drawn up opposite the feed centre. The driver was leaning on his elbow and looking at me. ‘Cristóbal –

por dónde andas?’

growled a deep, well-modulated voice.

‘Paco… it’s you!’ I responded, recognising the figure at the wheel. ‘You’re looking good, and I see you’ve joined the bearded men.’

Por dónde andas?

– literally ‘Where do you walk?’ – is a hard one to answer, though I suspect it’s a rhetorical greeting, and I have always responded to it as

such. I crossed the street and took Paco’s hand. His face burst into a great smile beneath the new beard.

‘Qué dice el hombre?’

he said.

Now,

Qué dice el hombre?

– ‘What does the man say?’ – is an even more abstruse sort of a greeting in my opinion than

por dónde andas?

I mean, what is the man supposed to say in reply to that? I’m always a little flummoxed by these formulaic Spanish greetings, fearing that despite years of residence I still don’t quite pass muster in this most basic communication.

‘Great to see you, Paco,’ I offered. ‘It’s been a long time, and apart from the fungal growth you look well. And how about Consuelo and Paz?’

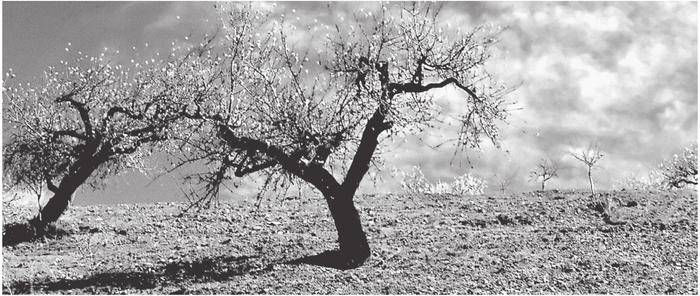

‘We’re all well, by the grace of God. But I’ve had a thought, Cristóbal, and here is my thought: do you not think it a good idea that we should go again to the hills of the Contraviesa and enjoy the beauty of the almond blossom?’

‘Hell yes, Paco. I was thinking of ringing you to suggest it, because it’s already fading on the lower hills…’

‘There’s still time: if we go higher we’ve still got a couple of weeks.’

Paco is my only country Spanish friend who would suggest such a thing. Other country people I know are not unaware of the beauty of nature and the countryside around them; they just live and work amongst it, rather than taking active steps to seek it out. The idea of walking into the hills to find the most spectacular grove of

blossoming

almonds would no more occur to them than it would occur to a commuter to hop off a train a stop early simply to admire the station. ‘I’ll give you a ring next week, then, and we’ll make a date,’ I said, and Paco slipped the van into gear and rolled round the corner.

Paco Sanchez is remarkable in lots of ways. He was born into a farming family in Torvizcón, where he lives to this day. His father made his living from growing vegetables, and as a child Paco would always be with him in the

huerto,

watching and learning. At eighteen he pulled together enough money to buy a team of mules, with which he scraped a desperately hard living ploughing the steep hills around the village.

There was some wild gene in his make-up, though, that made Paco a Communist, a seeker and a traveller, and with Consuelo, his bride from the village, he left home to seek his fortune in Switzerland. They worked as farm

labourers

, wherever they could find a job, and saved pretty much every Swiss franc they earned. The scheme was conceived to return to Spain with enough money to buy a patch of land – for Paco’s father had been a

jornalero,

a day worker with little land of his own. After several years the couple came back to Torvizcón with the funds to buy a house in the village, a fertile plot of alluvial silt down in the river, a small grove of olives and a whole hillside of almond trees up on the Contraviesa. In those days nobody wanted to buy property in the countryside, let alone farm it, so it was cheap.

They lost no time in making the land pay, and within a very few years were running a thriving business. Paco had been fired up with new notions from his time in Switzerland and was probably the first man in the Alpujarras to espouse the cause of organic agriculture, which contributed even more to his neighbours’ conviction that he was a dangerous radical. At the time this was flying

in the face of the wind, as all his contemporaries were embracing the racy modern chemical way of farming. Paco told me that he was doing nothing new; he was simply putting into practice all that he had learned from his father. In those days, everybody had farmed organically – nobody could afford the new chemicals and artificial fertilisers – so results were achieved by dint of skill, observation and a grinding round of work.

Paco and Consuelo were good at what they did, and had the imagination and confidence to look beyond the local market to sell their produce. They discovered an organic food outlet in Germany and started gearing their output to its tastes. They produced

pan de higo

(fig bread), almonds and jams and conserves of every sort of fruit; they pickled peppers and capers and dried tomatoes in the sun, as well as apricots, persimmons and loquats. Preserved olives they sold by the bucket, and olive oil and even the odd crate of Paco’s home-made wine – which, if the truth be told, was a bit of a hit-and-miss affair. Every month or so a van would come down from the organic co-operative in Germany and return laden with the delicious products of Paco and Consuelo’s industry. On the proceeds, they bought a big white van of their own and, not without misgivings, exchanged the team of mules for a small bulldozer.

But one of the effects of Paco’s wild gene, and avid

reading

on ecological matters, was to make him a little radical and even puritanical in his aims. The business of shipping the delights of the Alpujarras all the way to Hamburg for the benefit of its well-heeled denizens didn’t seem quite right to him. So he decided to set up a local co-operative in order to bring together the increasing number of organic growers and consumers in the Alpujarras.

I don’t know how Paco had the energy, after long hot days spent labouring amongst his fruit and vegetables and then driving around the Alpujarras to distribute boxes of produce, but somehow he managed to convene a meeting of interested parties. As I had written a book, it was felt I would ‘lend weight’ to the proceedings, so I was nominated to be

vocal,

or spokesperson, with special responsibility for co-ordinating the livestock sector. I was, in fact, the only member with any livestock, beyond the odd chicken, which meant that I had to co-ordinate myself. This was not as easy as you’d think, due to my tendency to fall asleep once the first item on the agenda was called and to doze quietly all the way through to ‘any other business’ – the inevitable result of a combination of hot night air, alcohol and the drone of voices arguing interminably over fine procedural points. At the first meeting I jerked awake to discover my vote was required to establish the name of the group. Paco had suggested ‘Alcaparra’, meaning ‘caper’, which struck me as a fine name for an agricultural co-operative. There wasn’t much competition so

Alcaparra

it was, and I was able to return to my slumbers.

The co-operative leased a small shop in town, which soon became a gathering point for the local alternative community. On sale were honeys and tofu and natural cosmetics made from avocado pears and other unlikely ingredients, but mostly mountains of rather

unprepossessing

vegetables. When it was

habas

(broad beans) season the shop would be crammed from floor to ceiling with

habas.

But of course everybody had their own habas, so nobody wanted to buy them. It was the same with

artichokes

– there’s only so many things you can do with an artichoke – and not much more promising for tomatoes,

peppers, aubergines and beans. As for oranges or lemons, they were a complete waste of time, as everybody had trees of their own.

In order to breathe some life into the livestock sector, I stuck up in the shop what I considered to be humorous posters, advertising succulent locally produced lamb. The response was, to say the least, poor, because ninety-nine per cent of the membership was vegetarian – and if they weren’t that, then they were vegan, or were fasting.

Unsurprisingly I began to feel redundant at meetings and little by little my attendance dropped off. Paco, who had been voted president by unanimous consent, was so efficient and seemed so good at maintaining order among the co-op’s more anarchic elements that I felt sure I wouldn’t be missed. But before long, I heard of bitter disputes erupting about what constituted organic produce – did you have to grow it yourself or could you do things like import herbs and spices from India? Paco thought the group shouldn’t be too puritanical, but he was out-voted by the organo-fundamentalists and eventually expelled. And the co-operative he had so painstakingly set up slid down the tubes.

A revival of the Almond Blossom Appreciation Society, as Paco had dubbed our previous year’s outing, would be just the thing to rise above such setbacks. I consulted Ana about the possibility of being given a free day to go walking in the mountains with my friend. There was an element of

suspicion

in the look she gave me. I fear that women in general are unable to rid themselves of the notion that, when men

go off on a jaunt together, they inevitably descend to

boozing

and licentiousness. I reminded her of how the previous year Paco and I had returned from our Almond Blossom Appreciation having imbibed nothing but water all day. I don’t think we even had anything to eat. Such was the purity of our motives.

‘Hmm?’ mused Ana sceptically. ‘Then why are you making such a point of asking me? It smacks of a guilty conscience.’ Which just goes to show how undervalued consideration and transparency can be.

Undeterred, I drove Chloë to school the next day, which gave me an early start. An Almond Blossom Appreciation expedition is a thing to be taken seriously, not an excuse to linger in bed till the middle hours of the morning. As I headed over the Seven-Eye Bridge and turned east towards Torvizcón, I gazed up at the three great snow-cloaked peaks of the Sierra Nevada. The early morning sun, just rising over the bulk of the Contraviesa, illuminated the high

eastfacing

slopes with a pale tinge of rose. Before long I swung round the bend into the Rambla de Torvizcón and saw the village lurking in its cleft down by the dry river. When the slopes above it are arrayed in almond blossom and the blue smoke from the village fires curls upwards into the bright winter sky, that’s the time to see Torvizcón. In the heat of summer, with the life and the colour baked out of the hills around, you’d best stay on the road and keep on going towards the Eastern Alpujarras.

I parked in the square and headed up the hill towards Paco’s house. It’s a stiff climb because Torvizcón is a steep village and Paco and Consuelo live at the top. I was panting hard by the time I got to the steep alley with its diagonal ridges to give a purchase to passing mules.

‘

Hola

, Paco!’ I called as I rounded the corner.