Read The Bell Curve: Intelligence and Class Structure in American Life Online

Authors: Richard J. Herrnstein,Charles A. Murray

Tags: #History, #Science, #General, #Psychology, #Sociology, #Genetics & Genomics, #Life Sciences, #Social Science, #Educational Psychology, #Intelligence Levels - United States, #Nature and Nurture, #United States, #Education, #Political Science, #Intelligence Levels - Social Aspects - United States, #Intellect, #Intelligence Levels

The Bell Curve: Intelligence and Class Structure in American Life (44 page)

Some of the more cynical dismissals of American political life are

similarly answered. Poor and humble workers, it is sometimes argued, are disenfranchised whether they vote or not, because the government does the bidding of the rich and well placed. It is small wonder, then, that they do not vote, this argument continues. But the evidence shows it is not so much the poor and humble who fail to vote; it is the uneducated. It may be easy to believe that the poor are disenfranchised, but it is less obvious why it should be the uneducated (poor or not). What is the cynic to make of the fact that an underpaid but well-educated shop clerk is more likely to vote than a less educated, rich businessman?

The link between education and voting is clear. Does it really signify a link between cognitive ability and voting? There is an indirect argument that says yes, described in the notes,

27

but we have been able to find only two studies that tackle the question directly.

The first did not have an actual measure of IQ, only ratings of intelligence by interviewers, based on their impressions after some training. This is a legitimate procedure—rated intelligence is known to correlate with tested intelligence—but the results must be treated as approximate. With that in mind, a multivariate analysis of a national sample in the American National Election study in 1976 showed that, of all the variables, by far the most significant in determining a person’s political sophistication were rated intelligence and expressed interest. Interest, however, was itself most tellingly affected by intelligence.

28

The more familiar independent variables—education, income, occupational status, exposure to the media, parental interest in politics—had small or no effects, after rated intelligence was taken into account.

The one study of political involvement that included a test of intelligence was conducted in the San Francisco area in the 1970s. The intelligence test was a truncated one, based on a dozen vocabulary items.

29

About 150 people were interviewed in depth and assessed on political sophistication, which is known to correlate with political participation.

30

The usual background variables—income and education, for example—were also obtained. Educational attainment was, as expected, correlated with the test score. But even this rudimentary intelligence test score predicted political sophistication as well as education did. To Russell Neuman, the study’s author, “the evidence supports the

idea of an independent cognitive-ability effect” as part of the proved link between socioeconomic status and political participation.

31

We do not imagine that we have told the entire story of political participation. Age, sex, and ethnic identity are among the individual factors that we have omitted but that political scientists routinely examine against the background of voting laws, regional variations, historical events, and the general political climate of the country. In various periods and to varying degrees, these other factors have been shown to be associated with either the sheer level of political involvement or its character. Older people, for example, are more likely to vote than younger people, up to the age at which the debilities of age intervene; women in the past participated less than men, but the gap has narrowed to the vanishing point (especially for educated men and women); different ethnic groups resonate to different political causes.

32

Our focus on education and intelligence similarly gives insufficient attention to other personal traits that influence political participation.

33

People vary in their sense of civic duty and in the strength of their party affiliations, apart from their educational or intellectual level; their personal values color their political allegiances and how intensely they are felt. Their personalities are expressed not just in personal life but also in their political actions (or inactions).

The bottom line, then, is not that political participation is simple to describe but that, despite its complexity, so narrow a range of individual factors carries so large a burden of explanation. For example, the zero-order correlations between intelligence and the fourteen political dimensions in the study of high school students described above ranged from .01 to .53, with an average of .22; the average correlation with the youngsters’ socioeconomic background was .09.

34

For the sentiment of civic duty—the closest approximation to civility in this particular set of dimensions—the correlation with intelligence was .4. As we cautioned above, this may be an overestimate, but perhaps not by much: The zero-order correlation between scores on a brief vocabulary test and the political sophistication of a sample of adults was .33.

35

The coefficients for rated intelligence in a multivariate analysis of political sophistication were more than twice as large as for any of the other variables examined, which included education, occupation, age, and parental interest in politics.

The coherence of the evidence linking IQ and political participation

as a whole cannot be neglected. The continuity of the relationship over the life span gives it a plausibility that no single study can command. The other chapters in Part II have shown that cognitive ability often accounts for the importance of socioeconomic class and underlies much of the variation that is usually attributed to education. It appears that the same holds for political participation.

The NLSY does not permit us to extend this discussion directly. None of the questions in the study asks about political participation or knowledge. But as we draw to the close of this long sequence of chapters about IQ and social behavior, we may use the NLSY to take another tack.

For many years, “middle-class values” has been a topic of debate in American public life. Many academic intellectuals hold middle-class values in contempt. They have a better reputation among the public at large, however, where they are seen—rightly, in our view—as ways of behaving that produce social cohesion and order. To use the language of this chapter, middle-class values are related to civility.

Throughout Part II, we have been examining departures from middle-class values: adolescents’ dropping out of school, babies born out of wedlock, men dropping out of the labor force or ending up in jail, women going on welfare. Let us now look at the glass as half full instead of half empty, concentrating on the people who are doing everything right by conventional standards. And so, to conclude Part II, we present the Middle Class Values (MCV) Index. It has scores of “Yes” and “No.” A man in the NLSY got a “Yes” if by 1990 he had obtained a high school degree (or more), been in the labor force throughout 1989, never been interviewed in jail, and was still married to his first wife. A woman in the NLSY got a “Yes” if she had obtained a high school degree, had never given birth to a baby out of wedlock, had never been interviewed in jail, and was still married to her first husband. People who failed any one of the conditions were scored “No.” Never-married people who met all the other conditions except the marital one were excluded from the analysis. We also excluded men who were not eligible for the labor force in 1989 or 1990 because they were physically unable to work or in school.

Note that the index does not demand economic success. A man can earn a “Yes” despite being unemployed if he stays in the labor force. A woman can be on welfare and still earn a “Yes” if she bore her children

within marriage. Men and women alike can have incomes below the poverty line and still qualify. We do not require that the couple have children or that the wife forgo a career. The purpose of the MCV Index is to identify among the NLSY population, in their young adulthood when the index was scored, those people who are getting on with their lives in ways that fit the middle-class stereotype: They stuck with school, got married, the man is working or trying to work, the woman has confined her childbearing to marriage, and there is no criminal record (as far as we can tell).

What does this have to do with civility? We propose that even though many others in the sample who did not score “Yes” are also fine citizens, it is this population that forms the spine of the typical American community, filling the seats at the PTA meetings and the pews at church, organizing the Rotary Club fund-raiser, coaching the Little League team, or circulating a petition to put a stop light at a dangerous intersection—and shoveling sidewalks and returning lost wallets. What might IQ have to do with qualifying for this group? As the table shows, about half of the sample earned “Yes” scores. They are markedly concentrated among the brighter people, with progressively smaller proportions on down through the cognitive’classes, to an extremely small 16 percent of the Class Vs qualifying.

| Whites and the Middle-Class Values Index | |

|---|---|

| Congnitive Class | Percentage Who Scored “Yes” as of 1990 |

| I Very bright | 74 |

| II Bright | 67 |

| III Normal | 50 |

| IV Dull | 30 |

| V Very Dull | 30 |

| Overall | 51 |

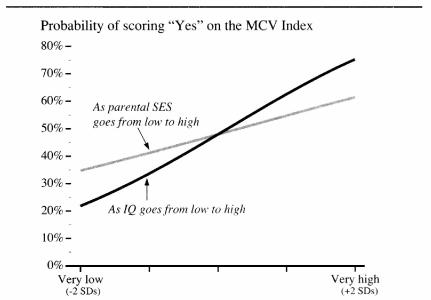

Furthermore, as in so many other analyses throughout Part II, cognitive ability, independent of socioeconomic background, has an important causal role to play. Below is the final version of the graphic you have seen so often.

Cognitive Ability and the Middle Class Values Index

Note: For computing the plot, age and either SES (for the black curve) or IQ (for the gray curve) were set at their mean values.

As intuition might suggest, “upbringing” in the form of socioeconomic background makes a significant difference. But for the NLSY sample, it was not as significant as intelligence. Even when we conduct our usual analyses with the education subsamples—thereby guaranteeing that everyone meets one of the criteria (finishing high school)—a significant independent role for IQ remains. Its magnitude is diminished for the high school sample but not, curiously, for the college sample. The independent role of socioeconomic background becomes insignificant in these analyses and, in the case of the high-school-only sample, goes the “wrong” way after cognitive ability is taken into account.

Much as we have enjoyed preparing the Middle Class Values Index, we do not intend it to become a new social science benchmark. Its modest goals are to provide a vantage point on correlates of civility in a population of young adults and then to serve as a reminder that the old-fashioned virtues represented through the index are associated with intelligence.

Cognitive ability is a raw material for civility, not the thing itself Suppose that the task facing a citizen is to vote on an initiative proposing some environmental policy involving (as environmental issues usually do) complex and subtle trade-offs between costs and benefits. Above-average intelligence means that a person is likely to be better read and better able to think through (in a purely technical sense) those tradeoffs. On the average, smarter people are more able to understand points of view other than their own. But beyond these contributions of intelligence to citizenship, high intelligence also seems to be associated with an interest in issues of civil concern. It is associated, perhaps surprisingly to some, with the behaviors that we identify with middle-class values.

We should emphasize that vast quantities of this raw material called intelligence are not needed for many of the most fundamental forms of civility and moral behavior. All of us might well pause at this point to think of the abundant examples of smart people who have been conspicuously uncivil. Yet these qualifications notwithstanding, the statistical tendencies remain. A smarter population is more likely to be, and more capable of being made into, a civil citizenry. For a nation predicated on a high level of individual autonomy, this is a fact worth knowing.

The National Context

Part II was circumscribed, taking on social behaviors one at a time, focusing on causal roles, with the analysis restricted to whites wherever the data permitted. We now turn to the national scene. This means considering all races and ethnic groups, which leads to the most controversial issues we will discuss: ethnic differences in cognitive ability and social behavior, the effects of fertility patterns on the distribution of intelligence, and the overall relationship of low cognitive ability to what has become known as the underclass. As we begin, perhaps a pact is appropriate. The facts about these topics are not only controversial but exceedingly complex. For our part, we will undertake to confront all the tough questions squarely. We ask that you read carefully.