The Body Hunters

Authors: Sonia Shah

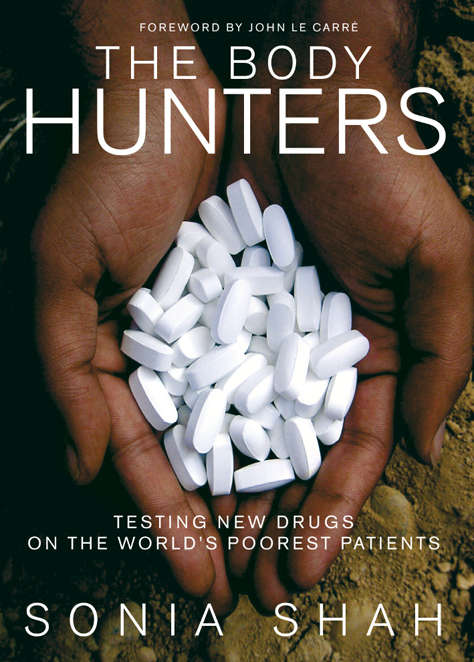

THE BODY HUNTERS

Â

Also by Sonia Shah

Crude: The Story of Oil

THE BODY HUNTERS

Testing New Drugs on the World's

Poorest Patients

SONIA SHAH

Â

Â

NEW YORK

LONDON

Foreword © 2006 by David Cornwell

© 2006 by Sonia Shah

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced, in any form, without written permission from the publisher.

Requests for permission to reproduce selections from this book should be mailed to: Permissions Department, The New Press, 38 Greene Street, New York, NY 10013.

Published in the United States by The New Press, New York, 2006

Distributed by W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., New York

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Shah, Sonia.

The body hunters : testing new drugs on the world's poorest patients / Sonia Shah.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN-13: 978-1-59558-831-9

1. Pharmaceutical policyâDeveloping countries. 2. Pharmaceutical industryâCorrupt practicesâDeveloping countries. 3. DrugsâPrescribingâDeveloping countries. 4. Drug utilizationâDeveloping countries. 5. Medical ethics. I. Title.

RA401.D44S53

2006

362.17'82âdc22 | 2005058394 |

The New Press was established in 1990 as a not-for-profit alternative to the large, commercial publishing houses currently dominating the book publishing industry. The New Press operates in the public interest rather than for private gain, and is committed to publishing, in innovative ways, works of educational, cultural, and community value that are often deemed insufficiently profitable.

Composition by Westchester Book Composition

This book was set in Palatino

10

9

8

7

6

5

4

3

2

1

Â

1

Clinical Trials Go Global

Â

3

Growing the Pharma Monolith

Â

5

HIV and the Second-rate Solution

Â

6

South Africa: Drug Trials and AIDS Denialism

Â

7

Outsourcing to India: The One Billion Body Politic

Â

8

Calibrating Ethical Codes

Â

9

The Emperor Has No Clothes: The Vagaries of Informed Consent

JOHN LE CARRÃ

This book is an act of courage on the part of its author and its publishers. Ever since I wrote

The Constant Gardener

, I have received approaches, and sometimes complete typescripts, from investigative writers determined to lift the veil on the darker side of the world's most profitable trade: the pharmaceutical industry. Where a proposed book seemed to have merit, and was not weighed down with mountains of medical jargon, I passed the word to literary agents and publishers' readers. Yet not one of the authors, so far as I was ever aware, saw his project realized. And if, months later, I delicately inquired why not, the answer, however wrapped up, was always the same: too risky.

And you might find it comic or outrageous or, if you are of my mind-set, illustrative of the stranglehold of unrestricted corporate power that the topic that is closest to all our lives, and closest to the concerns and responsibilities that we feel for one another, should be deemed too risky for public debate.

You might also find it outrageous that our treasured legal system, originally designed to protect our freedoms, should be the instrument of their suppression. Yet such is the reputation of the gunslinging lawyers of Big Pharma, so unlimited the industry's wealth, so vast its reach into politics, the media, and the very heart of the medical profession and the bureaucracy that sustains

it, that publishers have good reason to believe that, in picking a fight with Big Pharma, they are committing their company to a five-star lawsuit, countless hours of office time, disenchanted stockholders, and copies pulped before they reach the stores.

Yet, little by little, the veil is indeed being lifted. The outsourcing of clinical trials to countries where sick people are so poor they are ready to sign up to anything, whether or not they can read what's on the consent form, is now public knowledge. The tendency of Big Pharma to promote phantom, or at best speculative, maladies and then supply the cure for them, is now public knowledge.

The corrupt recruitment of large numbers of doctors in general practice and teaching hospitals to prescribe a particular medical project is now public knowledge

The corrupt recruitment of large numbers of doctors in general practice and teaching hospitals to prescribe a particular medical product is now public knowledge.

The ever-growing list of dangerously under-tested products that have been wished upon the public by supposedly impartial government bodies is public knowledge, as are the links between members of such bodies and the pharmaceutical companies that manufactured them.

It is also public knowledge, since they themselves have owned to it, that learned medical journals of supposed integrity have carried glowing accounts of this or that pharmaceutical product, only to discover they were written not by the august Professor of Something who has put his name to them but by their manufacturers.

But perhaps the worst of Big Pharma's many sins is its persistent encroachment, by means of a combination of lavish sponsorship and moral blackmail, on the integrity of biomedical research at every level, with the consequent ever-growing scarcity of unbought medical minds.

Using clear, accessible language and carefully annotated case histories, Sonia Shah has struck a blow for all who dream of harnessing

the huge power for good that is invested in the pharmaceutical industry, of seeing its products made available to those who most need them, and of curtailing the greed that drives its worst practices.

Â

Cornwall, England

February 2006

“The blood of those who will die if biomedical research is not pursued will be upon the hands of those who don't do it.”

âJoshua Lederberg, PhD, Nobel laureate

1

“I mean, shit, we learn by climbing over the bodies of humans.”

âMurray Gardner, MD, University of California

HIV researcher

2

“Field trials are indispensable. . . . If, in major medical dilemmas, the alternative is to pay the cost of perpetual uncertainty, have we really any choice?”

âDonald Frederickson, MD, former National

Institutes of Health (NIH) director

3

My life and the lives of some of my closest relatives continue thanks to the interventions of modern medicine, a scientific art that has marched forward in fits and starts on a bedrock of clinical research. The drugs that enabled me to survive an emergency cesarean section, those that allow my son to breathe despite allergic asthma, the other ones that correct a hormonal deficit in my mother have been administered to us with success and confidence in part because they've been tested in hundreds and perhaps thousands of human subjects in experimental trials. Not only that: these successful

drugs emerge from a slurry of countless other failed drugs, each of which was also tested on scores of warm bodies, some of which may have been harmed by their shortcomings.

There's nothing terrible about the truth that medical research imposes burdens. But generally speaking, we don't like to know it. We don't like to see it. The very notion of experimenting upon humans sounds sinister. And yet, if anything, we only want ever more drugs to help or enhance us, and more data to assure our trembling selves of their safety and effectiveness. The response to these contradictory desires has been the same since the mid-1800s, when scientists hell-bent on dissecting animals skirted the outcries of British antivivisectionists by cloaking their slicing in secrecy. Today, savvy drugmakers loudly publicize new medical products, but conduct the required experimentation quietly. And so, while we exult in, bicker over, and complain about the products of medical researchâhow much do the drugs cost? who pays? what are the side effects?âthe vast business of percolating new drugs burrows underground.

If the history of human experimentation tells us anything, from the bloody vivisections of the first millennium to the Tuskegee Syphilis Study, it is that the potential for abuse will fall heaviest on the poorest and most powerless among us.

The trend within the drug industry to conduct their experimental drug trials in poor countries is, as yet, in its infancy. But it is growing fast. Major drugmakers such as GlaxoSmithKline, Wyeth and Merckâalready conducting between 30 and 50 percent of their experiments outside the United States and Western Europeâplan to step up the number of their foreign trials by up to 67 percent by 2006, according to

USA Today

. And while armies of clinical investigators in the United States shrink, dropping by 11 percent between 2001 and 2003, those abroad fatten, increasing by 8 percent over the same period, according to a 2005 study by the Tufts Center for Drug Development. “The outsourcing of drug research is beginning to accelerate,” reported the

Washington Post

in May 2005.

4

And all the pressures on the profit-driven industry, pushing it toward speed and ever-lower costs; Americans' contradictory love of new drugs and skittishness about participating in the experiments that make them possible; the increasing desperation of hordes of patients in developing countries deprived access to useful medicines; and the immediate financial needs of the cash-strapped public hospitals and clinics meant to serve them suggest the trend will only grow over the coming years. Many leaders in developing countries, faced with crumbling facilities, minuscule budgets, and towering health crises make arrangements for more industry trials, not fewer.

It is a trend that cries out for public review. That's because the consequences of the multinational drug industry's trek into the developing world go far beyond the fates of the patients roped into their trials and then discarded afterward. After all, many will be helped, at least for the brief moments of their participation, and that is not insignificant.

More troubling are the potential implications for health care in poor countries. As clinical trials become an ever-larger cash cow for strapped hospitals and clinics, a larger portion of scarce resources gets diverted away from providing care. In many countries governments have stoked the trend by tightening up patent laws, easing ethics reviews of experiments, and converting medical record keeping into industry-friendly English. Nurses, doctors, and other clinicians already overwhelmed with needy patients find themselves with even less time for healing when institutional priorities shift from treating the ill to experimenting upon them for drug companies. And whether it is a quickie experiment or a well-intentioned study, if ethical oversight is shoddy or patient subjects uncomprehending of its purposes, the mistrust engendered runs deep, contaminating all of Western medicine's offerings, including life-saving vaccines and medicines.