The Collected Works of Chögyam Trungpa: Volume Five (13 page)

Read The Collected Works of Chögyam Trungpa: Volume Five Online

Authors: Chögyam Trungpa

As Dorje Trolö’s crazy wisdom expanded, he developed an approach for communicating with future generations. In relation to a lot of his writings, he thought, “These words may not be important at this point, but I am going to write them down and bury them in the mountains of Tibet.” And he did so. He thought, “Someone will discover them later and find them extraordinarily mind-blowing. Let them have a good time then.” This was a unique approach. Gurus nowadays think purely in terms of the effect they might have now. They do not consider trying to have a powerful effect on the future. But Dorje Trolö thought, “If I leave an example of my teaching behind, even if people of future generations do not experience my example, just hearing my words alone could cause a spiritual atomic bomb to explode in a future time.” Such an idea was unheard-of It is a very powerful thing.

The spiritual force of Padmasambhava as expressed in his manifestation as Dorje Trolö is a direct message that no longer knows any question. It just happens. There is no room for interpretations. There is no room for making a home out of this. There is just spiritual energy going on that is real dynamite. If you distort it, you are destroyed on the spot. If you are actually able to see it, then you are right there with it. It is ruthless. At the same time, it is compassionate, because it has all this energy in it. The pride of being in the state of crazy wisdom is tremendous. But there is a loving quality in it as well.

Can you imagine being hit by love and hate at the same time? In crazy wisdom, we are hit with compassion and wisdom at the same time, without a chance of analyzing them. There’s no time to think; there’s no time to work things out at all. It is

there

—but at the same time, it isn’t there. And at the same time also, it is a big joke.

Student:

Does crazy wisdom require raising your energy level?

Trungpa Rinpoche:

I don’t think so, because energy comes along with the situation itself. In other words, the highway is the energy, not your driving fast. The highway suggests your driving fast. The self-existing energy is there.

S:

You’re not worried about the car?

TR:

No.

Student:

Has the crazy-wisdom teaching developed in any lineages other than the Nyingma lineage?

Trungpa Rinpoche:

I don’t think so. There is also the mahamudra lineage, which is based on a sense of precision and accuracy. But the crazy-wisdom lineage that I received from my guru seems to have much more potency. It is somewhat illogical—some people might find the sense of not knowing how to relate with it quite threatening. It seems to be connected with the Nyingma tradition and the maha ati lineage exclusively.

Student:

What was the name of the Padmasambhava aspect before Dorje Trolö?

Trungpa Rinpoche:

Nyima Öser, “Holding the Sun.”

S:

Was that when he was with Mandarava?

TR:

No. Then he was known as Loden Choksi. In the iconography, he is wearing a white turban.

Student:

Are there any controls or precepts connected with crazy wisdom?

Trungpa Rinpoche:

Other than itself, there doesn’t seem to be anything. Just being itself.

S:

There are no guidelines?

TR:

There is no textbook for becoming a crazy-wisdom person. It doesn’t hurt to read books, but unless you are able to have some experience of crazy wisdom yourself through contact with the crazy-wisdom lineage—with somebody who is crazy and wise at the same time—you won’t get much out of books alone. A lot really depends on the lineage message, on the fact that somebody has already inherited something. Without that, the whole thing becomes purely mythical. But if you see that somebody does possess some element of crazy wisdom, that will provide a certain reassurance, which is worthwhile at this point.

Student:

Could you mention one of the spiritual time bombs, other than the lineage itself, that was left behind by Padmasambhava as a legacy and as a teaching that is relevant today?

Trungpa Rinpoche:

We might say this seminar is one of them. If we weren’t interested in Padmasambhava, we wouldn’t be here. He left his legacy, his personality, behind, and that is why we are here.

Student:

You mentioned some of the difficulties Padmasambhava faced in presenting the dharma to the Tibetans, principally that the Tibetans’ mental outlook was theistic while Buddhism is nontheistic. What are the difficulties in presenting the dharma to the Americans?

Trungpa Rinpoche:

I think it is the same thing. The Americans worship the sun and the water gods and the mountain gods—they still do. That is a very primordial approach, and some Americans are rediscovering their heritage. We have people going on an American Indian trip, which is beautiful, but the knowledge we have of it is not all that accurate. Americans regard themselves as sophisticated and scientific, as educated experts on everything. But still we are actually on the level of ape culture. Padmasambhava’s approach of crazy wisdom is further education for us—we could become transcendental apes.

Student:

Could you say something more about vajra pride?

Trungpa Rinpoche:

Vajra pride is the sense that basic sanity does exist in our state of being, so we don’t particularly have to try to work it out logically. We don’t have to prove that something is happening or not happening. The basic dissatisfaction that causes us to look for some spiritual understanding is an expression of vajra pride: we are not willing to submit to the suppression of our confusion. We are willing to stick our necks out. That seems to be a first expression of the vajra-pride instinct—and we can go on from there!

Student:

Two of the aspects of Padmasambhava seem to be contradictory. Padmasambhava allowed the confusion of the king to manifest and then turn back on itself, yet he didn’t allow the confusion of the five hundred pandits to manifest (if you want to call dualism confusion). He just destroyed them with a landslide. Could you comment on this?

Trungpa Rinpoche:

The pandits seem to have been very simple-minded people, because they had no connection with the kitchen-sink-level problems of life. They were purely thriving on their projection of who they were. So, according to the story, the only way to relate with them was to provide them with the experience of the landslide—a sudden jerk or shock. Anything else they could have reinterpreted into something else. If the pandits had been in the king’s situation, they would have been much more hardened, much less enlightened, than he was. They had no willingness to relate with anything at all, because they were so hardened in their dogmatism. Moreover, it was necessary for them to realize the nonexistence of themselves and Brahma. So they were provided with the experience of a catastrophe that was caused not by Brahma but by themselves. This left them in a nontheistic situation: they themselves were all that there was; there was no possibility of reproaching God or Brahma or whatever.

SIX

Cynicism and Devotion

H

OPEFULLY, YOU HAVE HAD

at least a glimpse of Padmasambhava and his aspects. According to tradition, there are three ways in which the life of Padmasambhava can be told: the external, factual way; the internal, psychological way; and the higher, secret way, which is the approach of crazy wisdom. We have concentrated on the secret way, with some elements of the other two.

By way of conclusion, it would be good to discuss how we can relate with Padmasambhava. Here, we are considering Padmasambhava as a cosmic principle rather than as a historical person, an Indian saint. Different manifestations of this principle appear constantly: Padmasambhava is Shakya Senge, the yogi Nyima Öser, the prince Pema Gyalpo, the mad yogi Dorje Trolö, and so forth. The Padmasambhava principle contains every element that is part of the enlightened world.

Among my students, a particular approach to the teachings seems to have developed. By way of beginning, we have adopted an attitude of distrust: distrust toward ourselves and also toward the teachings and the teacher—toward the whole situation in fact. We feel that everything should be taken with a grain of salt, that we should examine and test everything thoroughly to make sure it is good gold. In taking this approach, we have had to develop our sense of honesty—we have to cut through our own self-deceptions, which play an important part. We cannot establish spirituality without cutting through spiritual materialism.

Having already prepared the basic ground with the help of this distrust, it may be time to change gears, so to speak, and try almost the opposite approach. Having developed accurate and vajra-like cynicism and having cultivated vajra nature, we could begin to realize what spirituality is. And we find that spirituality is completely ordinary. It is completely ordinary ordinariness. Though we might speak of it as extraordinary, in fact it is the most ordinary thing of all.

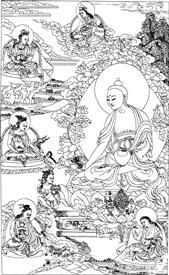

Shakya Senge.

To relate with this, we might have to change our pattern. The next step is to develop devotion and faith. We cannot relate to the Padmasambhava principle unless there is some kind of warmth. If we cut through deception completely and honestly, then a positive situation begins to develop. We gain a positive understanding of ourselves as well as of the teachings and the teacher. In order to work with the grace, or adhishthana, of Padmasambhava, with this cosmic principle of basic sanity, we have to develop a kind of romanticism. This is equally important as the cynical approach we have been taking up till now.

There are two types of this romantic, or bhakti, approach. One is based on a sense of poverty. You feel you don’t have it, but the others do. You admire the richness of “that”: the goal, the guru, the teachings. This is a poverty approach—you feel that these other things are so beautiful because you don’t have what they have. It is a materialistic approach—that of spiritual materialism—and it is based on there not being enough sanity in the first place, not enough sense of confidence and richness.

The other type of romantic approach is based on the sense that you do have it; it is there already. You do not admire it because it is somebody else’s, because it is somewhere far away, distant from you, but because it is right near—in your heart. It is a sense of appreciation of what you are. You have as much as the teacher has, and you are on the path of dharma yourself, so you do not have to look at the dharma from outside. This is a sane approach; it is fundamentally rich; there is no sense of poverty at all.

This type of romanticism is important. It is the most powerful thing of all. It cuts through cynicism, which exists purely for its own sake, for the sake of its own protection. It cuts through cynicism’s ego game and develops further and greater pride—vajra pride, as it is called. There is a sense of beauty and even of love and light. Without this, relating with the Padmasambhava principle is purely a matter of seeing how deep and profound you can get in your psychological experience. It remains a myth, something that you do not have; therefore it sounds interesting but never becomes personal. Devotion or compassion is the only way of relating with the grace—the adhishthana, or blessing—of Padmasambhava.

It seems that many people find this cynical and skeptical style that we have developed so far too irritatingly cold. Particularly, people who are having their first encounter with our scene say this. There is no sense of invitation; people are constantly being scrutinized and looked down upon. Maybe that is a very honest way for you to relate with the “other,” which is also you. But at some point, some warmth has to develop in addition to the coldness. You do not exactly have to change the temperature—intense coldness

is

warmth—but there is a certain twist we could accomplish. It lies only in our conceptual mind and logic. In reality, there is no twist at all, but we have to have some way of putting this into words. What we are talking about is irritatingly warm and so powerful, so magnetizing.

So our discussion of Padmasambhava seems to be a landmark in the geography of our journey together. It is time to begin with that romantic approach, if we may call it that: the sane romantic approach, not the materialistic romantic approach.

Our seminar here happened purely by accident, even though it involved a lot of organizing, working a lot of things out. But still it was worked out accidentally. It is a very precious accident that we were able to discuss such a topic as the life of Padmasambhava. The opportunity to discuss such a subject is very rare, unique, very precious. But such a rare and precious situation goes on constantly; our life as part of the teachings is extremely precious. Each person came here purely by accident, and since it was an accident, it cannot be repeated. That is why it is precious. That is why the dharma is precious. Everything becomes precious; human life becomes precious.