The Fields of Death (36 page)

Read The Fields of Death Online

Authors: Simon Scarrow

Napoleon shook his head. ‘No. I want the matter settled as soon as possible. I’ve spoken my mind; now let the ambassador carry the message back to his master.’

‘Sire,’Talleyrand turned in his chair so that he could face his Emperor more directly, ‘it would be wiser to confer with your advisors before agreeing on the form of any message to be sent to the Tsar. That would reduce the impact of any . . . inflammatory language, before it does any harm.’

‘Damn your diplomatic niceties!’ Napoleon snapped. ‘This has gone on long enough. Either the Tsar is a friend and ally, or he isn’t. I demand to know which path Alexander chooses.’

‘I am sure the Tsar wants peace,’ Talleyrand continued calmly. ‘Isn’t that so, Kurakin?’

The ambassador nodded, keeping a wary eye on Napoleon’s darkening expression as he did so. ‘Sire, with your permission, may I try to explain the Russian view of the situation?’

Napoleon took a calming breath and folded his arms. ‘By all means.’

‘Very well. When Russia looks towards Europe she sees an unbroken line of nations under the sway of France. She sees French troops in towns and fortresses along much of the frontier. We are not blind to the aspirations of the Poles towards becoming a fully fledged nation, with French encouragement. The antipathy between the Poles and Russia is as old as history and you would place a bitter enemy on our doorstep, sire.’

Kurakin paused and gently pushed his unfinished soup away from him. A servant nimbly reached round to remove the bowl as he continued, ‘Then there is the matter of the damage the Continental Blockade is causing to our economy. Every day the Tsar is deluged with petitions from merchants who are suffering because of France’s efforts to strangle trade with England. Even if the Tsar turns a blind eye to those who flout the blockade, our trade still suffers as French officials intervene further down the chain. Sire, it seems that you would beggar the whole of Europe to defeat the English. While I am confident that your imperial majesty will succeed in humbling England, we in Russia are looking to the future. With England reduced, what then will France aspire to? There are Bonapartes and Bonapartists on thrones across Europe. Your majesty is a man of ambition. We ask ourselves if such a man can ever be satisfied with what he already holds.’ Kurakin leaned back in his chair, his explanation concluded.

Talleyrand and Metternich glanced from the Russian to Napoleon, nervously trying to read his reaction.

Napoleon felt the blood drain from his face, and a cold rage seized his body, making his hands tremble. How dare the Russian accuse him so boldly? How could the Tsar betray the amity that Napoleon had so carefully contrived between the two of them? It was clear that every concession made to Russia had been taken as a matter of right. This was no alliance of mutual interest. It was the Tsar whose ambition was unbridled. He took everything and gave nothing. Why, when France had last faced Austria the campaign was over and peace declared long before the Tsar’s army had marched to assist his ally. Even then, the Tsar had taken the opportunity to snap up some of the Austrian lands bordering Russia. The fruits of a victory paid for by French blood, Napoleon concluded bitterly. He glared at Kurakin, tempted almost beyond endurance to explode and expose the duplicity of the Tsar, and those who lied on his behalf . . .

With a great effort, Napoleon held back his anger. This was not the time. His tirades were a weapon to be deployed with care. More often than not they were calculated to have a specific effect. Uncontained rage could be as dangerous to himself as it was frightening to others, if it then caused advisors to be restrained, and provoked enemies to revenge.

Napoleon glanced outside. Dusk was falling over the city and soon it would be dark enough for the fireworks. They were scheduled to begin after the dinner was over, but Napoleon’s suppression of his anger had left him feeling brittle and impatient. Abruptly, he waved to the chamberlain in charge of the entertainments and the man came hurrying over.

‘The dinner is over,’ Napoleon announced.

‘Over?’ The chamberlain raised his eyebrows. ‘What of the other courses, sire?’

‘They will not be needed. Pass the word to the officer in charge of the fireworks. I want the display to begin in thirty minutes.’

‘Yes, sire, but—’

‘But?’ Napoleon frowned at him and the chamberlain lowered his gaze nervously.

‘Yes, sire. As you command.’

The man bowed and backed away the regulation number of steps before turning to issue the orders to the staff waiting the tables. As soon as the Emperor’s guests had finished their soup the bowls were whisked away, and when the last of the waiters had filed out of the room the footmen stepped up behind the chairs. The chamberlain rapped his rod on the tiled floor and the conversation quickly died away.

‘At his majesty’s command, the banquet is over and his majesty is pleased to request that his guests now repair to the river terrace in preparation for the fireworks.’

The guests glanced at each other, surprised that the banquet to celebrate the coronation of the Emperor amounted to no more than a bowl of soup. At the head of the table, Napoleon abruptly rose to his feet, sweeping the napkin from his lap. The footman behind him just caught hold of the chair in time to prevent it from falling back, or scraping in an undignified manner. The Empress rose quickly and then the rest of the guests got to their feet. Napoleon turned to the footman.

‘Bring me my coat and hat.’

‘Yes, sire.’

As soon as he was well wrapped against the cold of the evening Napoleon led the way through the palace to the long wide terrace overlooking the Seine. Guardsmen were spaced at regular intervals overseeing the braziers that provided a little light and warmth for the small crowd filing out on to the terrace. As the crowds packed along the river bank saw the figures emerging from the Tuileries they let out a great cheer and the sound continued along the river, far beyond the range of those who could see the imperial party.

The Emperor and Empress took their seats, and once the other guests were in place he pulled out his pocket watch. Angling the face towards the nearest brazier he read the time, and then he replaced the watch in its fob. There were still ten minutes to go before the half-hour was up.

Napoleon coughed at the sharpness of the night air. ‘Tell them to start.’

The chamberlain opened his mouth slightly, then quickly nodded and hurried away. There was a band just below the terrace and a sudden beating of drums silenced the guests and the crowds. The pounding rhythm echoed off the surrounding buildings as tens of thousands of people waited excitedly for the spectacle to begin. Then the drums stopped, and a moment later the band struck up the

Marseillaise

. Along the river the people joined in and sang with full hearts as they were caught up in the thrill of the occasion. As the last note faded away there was a brief flicker out on one of the barges, then a flare of sparks and a brilliant thread of light as a rocket shot up towards the overcast sky with a harsh hiss. It exploded in a cloud of star-like sparks that briefly illuminated the scene below, and the crowd let out a collective sigh of pleasure. More rockets whooshed into the sky and burst overhead. On the two flanking barges, carefully arranged combinations of fireworks gushed fountains of red and white sparks into the air to accompany the rockets, and all the while the band continued to play patriotic tunes, competing with the crackle and detonations of the fireworks.

Marseillaise

. Along the river the people joined in and sang with full hearts as they were caught up in the thrill of the occasion. As the last note faded away there was a brief flicker out on one of the barges, then a flare of sparks and a brilliant thread of light as a rocket shot up towards the overcast sky with a harsh hiss. It exploded in a cloud of star-like sparks that briefly illuminated the scene below, and the crowd let out a collective sigh of pleasure. More rockets whooshed into the sky and burst overhead. On the two flanking barges, carefully arranged combinations of fireworks gushed fountains of red and white sparks into the air to accompany the rockets, and all the while the band continued to play patriotic tunes, competing with the crackle and detonations of the fireworks.

Napoleon watched the display with little pleasure. His mind was still concentrated on the accusations that the Russian ambassador had made against him. Every now and then, he glanced to his left and saw the profile of Kurakin, lit up by the lurid glare from the display. The Russian had overstepped the mark. In doing so, he was clearly repeating the views of his master back in St Petersburg. If that was the case, then Alexander was spoiling for war, despite any protestations to the contrary. In that light, every slight and snub that Napoleon had received at the hands of the Russians, every breach of the terms of their alliance, every expansion of Russian power over new tracts of land, was all calculated to provoke France into open conflict.

He felt a moment’s sadness at the memory of the friendship he had shared with the Tsar at Tilsit. For a time there he had felt a fondness for the Russian ruler, as an elder brother might feel for a sibling in need of guidance and a good example. Now he had been rejected, and, worse, the Tsar seemed bent on becoming the dominant voice in Europe, brooking no rival.

Across the water on the centre barge, a giant N flared into life and the Emperor’s guests applauded appreciatively. On the opposite side of the river, the letter was reflected in the water of the Seine and the crowd lifted their voices in a vast, deafening cheer.

Napoleon shifted in his chair and turned towards the Russian ambassador. ‘Kurakin!’

The man looked towards him, and Napoleon raised his voice so that as many as possible of his guests would hear. He stabbed his finger towards the ambassador. ‘You have enjoyed the spectacle?’

‘Yes, sire.’

‘Good. I want you to tell your master, the Tsar, that it is clear to me that he wants war with France. That is the only explanation behind all that he has done to undermine our alliance. He has proved himself a false friend. You tell him that if he wants war with France then he will have his war. I swear by all that is holy that I will wage it on a scale beyond anything that Europe has ever seen.’

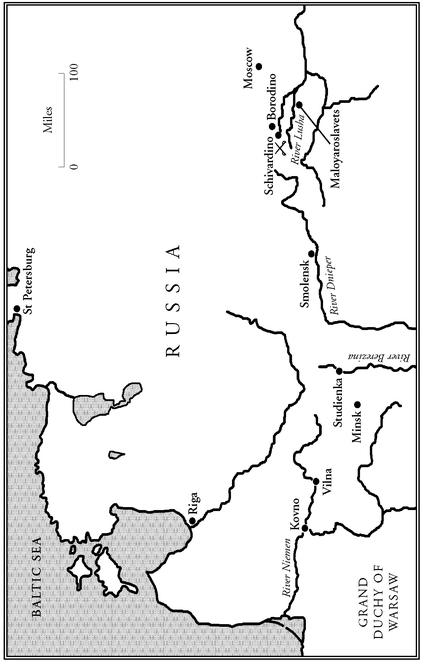

THE RUSSIAN CAMPAIGN 1812

Chapter 23

Paris, January 1812

Talleyrand looked up from the document and gently stroked his chin with the tips of his fingers while he digested the information.

‘Well?’ Napoleon’s voice broke into his thoughts. The Emperor was seated on the other side of the large table in the planning room of the Tuileries palace. A built-up fire blazed in the grate, casting a warm glow about the room, but not enough warmth for Talleyrand, sitting on the far side of the table. Behind him the tall windows overlooked the courtyard. Snow had fallen and blanketed the cobbles with an even layer, broken up now by the ruts of a handful of carriages and the footsteps of sentries. An icy wind was blowing across the city, occasionally rattling the windows and moaning across the chimney, causing the fire to flare and flicker.

‘What do you think?’ Napoleon pressed.

‘This list.’ Talleyrand tapped the document lightly. ‘This list of grievences, sire. What do you hope to achieve by presenting this to the Tsar?’

‘It will serve to remind him of all the agreements he has broken. It will provide the basis for a new agenda when we meet to renew our alliance.’

Talleyrand looked up. ‘A meeting has been arranged, then?’

‘No. Not yet. It is my hope that when the Tsar reads through the list of grievences and realises that the likelihood of war is very real, he will come to his senses and agree to negotiate.’

‘On these terms?’Talleyrand nodded at the document. ‘You say here that you demand that Russia enforces the Continental Blockade to the fullest extent. Our ambassador in St Petersburg says that there is a great deal of anger over the issue. Moreover, there are many in the Tsar’s court, and also officers in his army, who are openly demanding war with France. I suspect that Alexander is living in daily fear that some coterie of malcontents is already plotting his murder and preparing the way for a more belligerent ruler. Either way, war is a distinct possibility.’

‘It is more than possible, Talleyrand. It is inevitable, unless the Tsar bows to my demands.’

‘I see. Then this document is designed to provoke him into declaring war.’

‘I suspect that he will choose war as the lesser of two evils.’

Talleyrand stared at him.‘In my experience war is always the greatest of evils.’

‘You say that because you are not a soldier. There is more to war than death.’

‘Oh, yes, so I have heard. In addition to death, there is the devastation and despoiling that follows in the wake of an army. Hunger, looting, rape, torture and massacre. Not to mention the huge cost in gold that it takes to wage war on the scale that you envisage.’

Napoleon stared back at him. ‘You speak like the consummate civilian you are. If it were left to the likes of you, then every nation would be crawling on its belly, prostrating itself to its neighbours.’

Other books

Cole's Redemption (Love Amongst the Pines) by Curtis, Leigh

The Mystery at Monkey House by David A. Adler

Berserker (Omnibus) by Holdstock, Robert

The Abrupt Physics of Dying by Paul E. Hardisty

The Perfect Ghost by Linda Barnes

Wild Desire by Cassie Edwards

A Dance for Him by Richard, Lara

Crave by Bonnie Bliss

River Deep by Priscilla Masters

Glamour by Melody Carlson