The Hidden Gifts of the Introverted Child (5 page)

Read The Hidden Gifts of the Introverted Child Online

Authors: Marti Olsen Laney Psy.d.

A child’s genes encode the formulas that make up his or her brain chemicals and neurotransmitters. These formulas are biologically 99.9 percent the same in all humans—that’s why humans have common clusters of traits that produce certain patterns of behavior. But it’s that 0.1 percent difference in our inherited genetic chemical recipes that accounts for our individual differences, from height to hair color to who becomes a concert pianist.

So the first piece of this puzzle is that your genes, with millions of years of DNA coiled within (as Emily Dickinson presciently wrote in her poem), determine which neurotransmitters will govern your child’s brain.

Brain cells, or neurons, must communicate with one another to make the mind and body work. Picture the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, where God is reaching out to Adam. Their fingers a-l-m-o-s-t touch. Brain cells are like that: They almost touch. It’s in that slight space between the cells, called

synapses

, where all the action takes place. This is where messages can be shuttled from one cell to inform another cell.

These synapses, or “gaps of possibilities,” are the second piece of the puzzle. They allow neurotransmitters to travel over literally billions of routes to link cells together. But neurons have locks that admit only one neurotransmitter key. The key fits the cell’s lock and signals the cell to either “fire” or “stop firing.” If the cell fires, then that area of the brain goes to work and the child shows certain behaviors. If it doesn’t fire, it stays dormant and the behavior isn’t activated.

Brain Routes

The third piece of the puzzle is that each child’s brain creates different pathways as her or his main neurotransmitters consistently switch on or off specific cells. Neurons that fire together are wired together into chains of cells that become well-traveled pathways, forming networks in the brain. Scientists have been able to map these neurotransmitter pathways and networks and have determined what functions they affect. Traveling certain pathways more often than others, linking cells according to their own unique design, creates a child’s temperament.

Innies’ and Outies’ Favorite Neurotransmitters

“

The ultimate medical definition of life is brain activity

.…

It’s the first step toward achieving a more abundant life.” —Eric Braverman, M.D

.

J. Allan Hobson, a professor of psychiatry at Harvard, has written at length about the next piece of the puzzle: the influence of two specific neurotransmitters,

acetylcholine

and

dopamine

. According to Hobson, these two main chemical “jolt juices” significantly influence vital brain functions and therefore have a huge impact on behavior. They are two major circuits connecting all levels of the brain. Acetylcholine governs vital functions in the brain, including concentrating, consciousness, alert states, shifts between waking and sleeping, voluntary movement, and memory storage. The dopamine pathways represent the most powerful reward systems in the brain. They turn off certain types of complex brain functions and turn on involuntary movement, so they prompt children to act now and think later.

Bridging Mind and Body

The next puzzle piece is explained by leading brain researchers Stephen Kosslyn and Oliver Koenig in their book

Wet Mind

. They agree that acetylcholine and dopamine trigger the nervous system; indeed, they say these are the main links between the brain and the body. However, they note that they function on opposite sides of the autonomic nervous system: Dopamine activates in the

sympathetic

nervous system and acetylcholine operates in the

parasympathetic

nervous system. The sympathetic nervous system is the “fight, fright, or flight” system; the parasympathetic nervous system is the “rest and digest” system. Sure enough, studies show that introverts are dominant on the parasympathetic side of the nervous system, which uses acetylcholine as its main neurotransmitter. I have termed this the “Put on the Brakes” system. Extroverts are dominant on the sympathetic side of the nervous system, which uses dopamine as its main neurotransmitter. I call this the “Give It the Gas” system. I’ll get back to these two systems shortly.

Balancing Act

The final piece of the temperament puzzle are your child’s innate “set points.” Our genes create set points in our bodies to keep us alive. Set points are analogous to a home’s heating and cooling system with its built-in thermostat. You set it at the optimal point for you—say, sixty-eight degrees. When it dips too far below that temperature, your heater kicks in and warms up the house. If the house gets too hot, the air conditioning brings it back to the set point. Your child’s body is the same; it maintains homeostasis by staying within certain ranges. There are set points for vital bodily functions such as temperature, blood pressure, glucose, heart rate, and many others. Set points signal when they are getting out of range so that the body can take action to maintain

balance. For example, when your child’s temperature shoots up, her body attempts to cool her off by sweating, becoming less active, giving her the urge to throw off the covers, and sending blood to the skin to cool her interior.

THE BALANCING ACT

Innies and outies maintain balance when they are functioning around their “set point.” They can function outside their natural range for a short time. But they will be stressed if they have to stay out of range for too long

.

Brain researcher Allan Schore believes that temperament is molded by where a child’s set point lies along the natural introvert-extrovert continuum. This genetically determined set point is where this person’s brain and body function best with the least effort. The continuum is like a teeter-totter. A child can make small adjustments around his set-point range without losing too much energy or becoming too stressed. It is stressful and takes extra energy to function outside one’s range for any length of time.

Whether a child is an introvert or an extrovert is determined by where her set point falls on the systems that manage energy. Energy can be confusing because it’s constantly in flux. An innie might be well rested and lively one day and, then, if she hasn’t had sufficient recharging time, dragging her wagon the next. This lack of consistency can be really confusing to outies, who are almost always energetic. Introverts are conservers, and they recharge their energy in peace and quiet or by reducing external stimulation. Extroverts are energy spenders; they restore their energy by being out and about, being active, and being around other people.

This energy disparity has a tremendous impact on innies. Everything an innie does in the outside world requires an expenditure of energy. Everything an outie does in the outside world

gives

him

energy. This one detail makes a gigantic difference in how innies experience going out into the world. It also has a huge impact on how others perceive them.

Introversion and extroversion are not black and white. No one is completely one way or another—we all must function at times on either side of the continuum. But we do have dominant sides established by set points, so, just as all children are either right-or left-handed, right-or left-brained, and right-or left-eyed, we are all introverted or extroverted.

Try the following exercise to make this concept more tangible. Write a paragraph with your nondominant hand. Notice the energy it takes to write this, compared to writing with your dominant hand. Using your dominant hand is effortless; you don’t even have to consciously think about doing it. It’s where you function best and feel the most comfortable. But when you write with your nondominant hand, your penmanship deteriorates. It may even be harder to think. Likewise, using your nondominant foot won’t give you your most accurate kick on the soccer field.

Innie and Outie Reward Routes

“

To find for each person his true character, to differentiate him from all others, means to know him

.” —

Hermann Hesse

Let’s take a closer look at acetylcholine, the neurotransmitter that dominates for introverts. Acetylcholine triggers the brain’s ability to focus and concentrate deeply for long periods. It slows down the body when it is awake so the brain can concentrate. It can also signal the voluntary muscles to get up and go. Paradoxically, acetylcholine also paralyzes the body when you are asleep and fires up the brain during rapid eye movement (REM) dream sleep. During REM sleep, the brain is even more active than during the day.

“Jolt” and “No Jolt” Juices

Lots of neurotransmitters and other chemicals flow like a river of Jamba Juice through the brain. Each variety of neurotransmitter has a dedicated mission, resulting in different behaviors, thoughts, and emotions.

Neurotransmitters either excite or inhibit a brain cell. When they excite a chain of brain cells, it looks like a row of tumbling dominoes. When they inhibit, they tell the dominoes not to tumble.

These are the most important neurotransmitters and their main assignments:

Acetylcholine says, “Let’s think about it.”

This is the superstar of thought, concentration, and voluntary movement. It controls vital activities that govern arousal, attention, awareness, perceptual learning, sleep, and waking. It’s the main neurotransmitter used by innies’ “Put on the Brakes” nervous system. A deficiency of acetylcholine disrupts learning and cognitive function and causes memory loss. Acetylcholine neurons are the first to degenerate in Alzheimer’s disease.

Dopamine says, “If it feels good, do it.”

This is one of our most rewarding neurotransmitters. Dopamine regulates movement, pleasure, and action. It is essential for alert awareness, especially the feeling of excitement about something

new

. It’s the main neurotransmitter for outies, built by the building blocks released by the “Give It the Gas” nervous system. It is also the most addictive of all neurotransmitters.

Enkephalins and endorphins say, “I’m feeling no pain.”

Like pain medication, they dull pain, reduce stress, and promote a floaty, tranquil calm. They are activated to counteract stress. They, too, can be addicting. They are released during pain, relaxation practices, vigorous exercise, and eating red hot chili peppers.

Serotonin says, “Not too much and not too little.”

This “juice” helps to trigger sleep and affects mood, peace, and tranquillity. Yet it’s a puzzling neurotransmitter. You can’t be awake or concentrate without it, but too much and you feel tired and unfocused and may nod off. It’s the master impulse modulator. It inhibits aggression, depression, anxiety, and impulsivity while promoting calm. It is one of the main neurotransmitters used in antidepressants.

GABA says, “Chill out.”

This is the most widespread inhibitory neurotransmitter in the brain. Low GABA (gamma-aminobutyric acid) and low serotonin are related to high aggression and violence. Levels of GABA drop when watching violence. It suppresses emotion and is often used to treat anxiety.

Glutamate says, “Let’s party.”

Glutamate is the brain’s major “jolt juice.” Quick and clear thinking are impossible without it. If too much is constantly released, it causes the brain to burn itself out, as we see in users of methamphetamine or cocaine. It is vital for forging links between neurons for learning and long-term memory.

Norepinephrine says, “Better safe than sorry!”

It’s the alarm bell. It recognizes danger and organizes the brain to respond to it by releasing adrenaline. Adrenaline is related to tension, excitement, and energy. It is released by the “Give It the Gas” nervous system. It increases physical and mental arousal, heightens mood and vigilance, and enhances readiness to act.

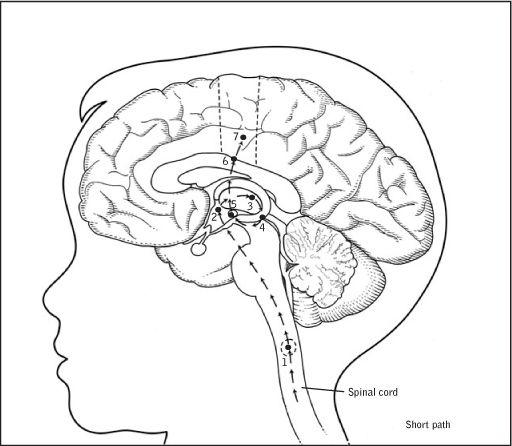

LONGER INTROVERT ACETYLCHOLINE PATHWAY

1. Reticular Activating System

—Activator: Acetylcholine activates the Front Attention System; signals “Something is interesting.”

2. Hypothalamus

—Master Regulator: Regulates basic body functions and turns on the braking side of the nervous system.

3. Front Thalamus

—Relay Station: Receives external stimuli, reduces it, and shuttles it to the front of the brain.

4. Right Front Insular

—Integrator: Combines emotional skills such as empathy and self-reflection; assigns emotional meaning, notices errors and makes decisions. Integrates slower “what” or “why” visual and auditory pathways.

5. Left-Mid Cingulate

—Social Secretary: Prioritizes, grants entry into CEO area; attends to the internal world. Emotions trigger the autonomic nervous system.

6. Broca’s Area

—Left Lobe: Plans speech and activates self-talk.

7. Right and Left Front Lobes

—CEO Processors: Acetylcholine creates beta waves and “hap hits” during high brain activity. Selects, plans, and chooses ideas or actions. Develops expectations. Evaluates outcomes.

8. Left Hippocampus

—Consolidator: Acetylcholine collects, stamps as personal, stores long-term memories.

9. Amygdala

—Threat System: Attends to threats with fear, anxiety, and anger. Signals social panic and triggers storage of negative experiences.

10. Right Front Temporal Lobe

—Processor: Integrates short-term memory, emotions, sensory input, and learning. Triggers voluntary muscles.

SHORTER EXTROVERT DOPAMINE PATHWAY