The Illusion of Conscious Will (32 page)

Read The Illusion of Conscious Will Online

Authors: Daniel M. Wegner

Tags: #General, #Psychology, #Cognitive Psychology, #Philosophy, #Will, #Free Will & Determinism, #Free Will and Determinism

When we see a person perpetrating one or the other of these blatant distortions, it is tempting to assume that the person is motivated by self-aggrandizement. We all know the soul who brags whenever something good comes of his or her action but who looks quickly to excuses or the meddling of others when the action falls short. The overgrown ego we attribute to this person seems to be a grasping, cloying, demanding entity, and the notion that the person is powered by selfish motives is a natural explanation (Miller and Ross 1975; Snyder, Stephan, and Rosenfield 1978). However, when we realize this person is assuming the self to be an ideal conscious agent, the striving seems understandable. The person who views actions as plausibly caused by the conscious will must necessarily complete the puzzle whenever parts are missing. Imagining oneself as a conscious agent means that conscious intention, action, and will must each be in place for every action. Intention and action imply will; intention and will imply action; and action and will imply intention. An ideal agent has all three. Putting these parts in place, it seems, involves constructing all the distortion of reality required to accommodate the birth of an ego.

6

Action Projection

The authorship of one’s own action can be lost, projected away from self to other people or groups or even animals.

Give the automaton a soul which contemplates its movements, which believes itself to be the author of them, which has different volitions on the occasion of the different movements, and you will on this hypothesis construct a man.

Charles Bonnet,

Essai de Psychologie

(1755)

When you do something, how do you know that you are the one who did it? And when someone else does something, how do you know that you

weren’t

the one who did it? These questions seldom arise in everyday conversation because the answer is usually obvious: Everybody

knows

that they are the authors of their own actions and

not

the authors of other people’s actions. If people got this sort of thing mixed up on a regular basis, right now you might think that you are the one who is writing this sentence and I might think that I am reading it. With such a break-down of the notion of personal identity, we might soon be wearing each other’s underclothing as well.

The fact that we seldom discover that we have confused our actions with those of others does not indicate, however, that this is impossible. Perhaps it happens all the time, but mostly we just don’t notice. The theory of apparent mental causation suggests that breakdowns in the sense of authorship do happen and in fact are quite likely under certain conditions. According to the theory, the actions our bodies perform are never self-evidently our own. We are merely guided in interpreting them as consciously willed by our “selves” because of our general human tendency to try to understand behavior in terms of the consciously willed action of specific minds—along with evidence that, in this particular case, the mind driving the action seems to be ours. The causal agent we perceive at our own core—the “I” to which we refer when we say we are acting—is only one of the possible authors to whom we may attribute what we do. We may easily be led into thinking there are others.

This chapter focuses on the inclination we have in certain circumstances to project actions we have caused onto plausible agents outside ourselves. These outside agents can be imaginary, as when people attribute their actions to spirits or other entities, and we turn to this possibility in

chapter 7

. The focus in this chapter is the more observable case of action projection to agents who are real—individual persons, groups of people, or sometimes animals. When we impute our actions to such agents, we engage in a curious charade in which we behave on behalf of others or groups without knowing we are actually causing what we see them doing. It is important to understand how this can happen—how things we have done can escape our accounting efforts and seem to us to be authored by others outside ourselves. If this is possible, our selves too, may, be merely

virtual

authors of action, apparent sources of the things our bodies and minds do.

The Loss of Authorship

How could normal people become convinced that something they are doing is actually being done by someone else? We have seen glimpses of this odd transformation in the case of automatisms; there is a fundamental uncertainty about the authorship of each person’s actions that becomes apparent in exercises such as table turning and Ouija spelling. People who do these things may make contributions to the movement of the table or the planchette that they attribute to others—either to the real people who are cooperating in the activity or to some imaginary agent or spirit invoked to explain the movement. These are not, however, the only circumstances in which action projection has been observed. There are a variety of cases in which errors in perceiving apparent mental causation lead people to misunderstand what it is they have consciously willed.

Perhaps the most elementary case is the

autokinetic effect

. This is the tendency to see an object, such as a point of light in a darkened room, moving when in fact the object is stationary and it is one’s eyes and body that are moving. Muzafer Sherif (1935) took advantage of this phenomenon in his studies of conformity. He told individuals that a light was going to be moved by an assistant in a darkened room, and he asked them judge how far it was moving. In some cases, the individuals were asked to make these judgments after hearing others describe what they saw, and it turned out that these estimates were influenced, often drastically, by what they heard others say. People would describe the light gyrating in circles, for example, if others before them said that this was what they saw. All the while, how-ever, the light was perfectly stationary. The fact is, sometimes it’s very difficult to discern that we are doing an action, and this is the starting point of many interesting errors—cases in which we project our own actions to the world around us.

Clever Hans

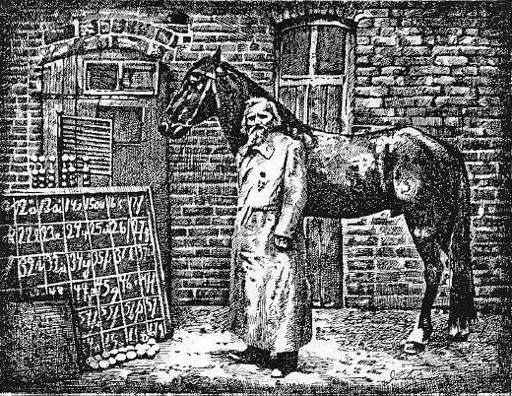

Some of the most famous examples of action projection involve the attribution of exceptional skills to animals. Clever Hans, a horse renowned in Berlin in 1904 for his astounding mental abilities, is a particularly well-documented case. Under the tutelage of the trainer Wilhelm von Osten, Hans could add, subtract, multiply, and divide, read, spell, and identify musical tones—giving his answers by tapping his hoof or with the occasional shake of his head for “no.” So, for example, on an occasion of being asked the sum of 2 5 and 1 2, Hans answered 9 10 (by first tapping the numerator, then the denominator). To the question, What are the factors of 28? Hans tapped consecutively 2, 4, 7, 14, 28. (He left out 1 by horsing around.) Von Osten made a letter board that enabled Hans to spell out answers to questions (

fig. 6.1

). Hans could recognize people and spell their names after having met them once. He could also tell time to the minute by a watch, and answer such questions as, How many minutes does the big hand travel between seven minutes after a quarter past the hour, and three quarters past? There were little things, too, that made the horse really convincing—for instance, when tapping out higher numbers, Hans went faster, as though he was trying to speed along.

The truly astonishing thing about Hans was his ability to answer questions offered by different people, even in the absence of trainer von Osten. Thisimmediately voided any suspicion of purposive deception by his trainer. Even people who dearly wanted to debunk Hans’s abilities found the darned horse could answer their questions all alone in a barn. Hans was debated in the newspapers of Germany for months, leading to a “Hans Commission” report by thirteen expert investigators in September 1904, which certified that the horse was in fact clever. But Hans’s feats were the topic of continued investigation by Oskar Pfungst (1911), a student of the psychologist (and commission member) Carl Stumpf. Pfungst carried out a series of studies of Hans that finally clarified the causes of the horse’s amazing behavior.

Figure 6.1

Trainer Wilhelm von Osten and his horse, Clever Hans, facing the letter board with which Hans spelled out answers to questions. From Fernald (1984). Courtesy Dodge Fernald.

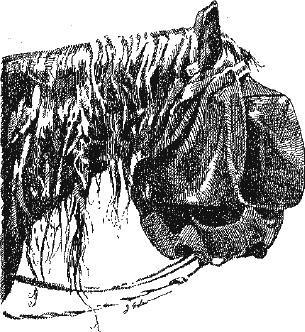

The principal observation that made Pfungst suspicious was the fact that Hans could not answer when he couldn’t see. A blinder wrapped around Hans’s head quickly put a stop to his cleverness (

fig. 6.2

). Having one’s head wrapped in a big bag might leave some of us humans unwilling to answer hard questions as well, but suspicions about Hans did not stop there. Pfungst went on to find that Hans also could not answer questions when the answer was unknown to a person. So in one experiment Pfungst spoke a number directly into the horse’s ear and then von Osten did so as well. When they called on the horse to report the sum of the two numbers, he was not able to do it, even though he could calculate sums given him by one person all day.

Figure 6.2

Clever Hans with a blindfold bag over his head. From Fernald (1984). Courtesy Dodge Fernald.

Eventually, Pfungst discovered a subtle mannerism in von Osten that also appeared quite unconsciously in most of Hans’s questioners. On asking Hans something, questioners would slightly incline their heads forward at the end of the question so as to see Hans’s hoof tapping. When a questioner did this, Hans began to tap out the answer. (Pfungst found that leaning forward would get Hans started tapping even without any question at all.) When Hans was tapping and the correct answer finally was reached, von Osten and most other questioners tended to straighten up, ever so slightly. Hans, sans the head-wrap, could time his tapping to start and stop by attending to these very delicate movements and so answer pretty much any question to which the questioner knew the answer. In a detailed test of this idea, Pfungst took the part of Hans tapping out answers and answered correctly the

unspoken

questions proffered by twenty-three of twenty-five questioners. Admittedly, attending to such tiny unconscious movements is fairly clever all by itself and must have been mastered by the horse only after considerable (inadvertent) training by von Osten. Indeed, Hans’s tendency to go fast for large numbers indicated that he was even attending to the degree of tilt of the questioner’s body because most people lean further forward the longer they expect to wait for the answer. However, even this keen perceptiveness doesn’t measure up to the feats of math, memory, and pure horse sense that everyone had imagined.

After Pfungst pointed all this out, von Osten was not the least bit convinced. He was adamant that Hans was not merely reading the inclinations of his body. Pfungst explained in detail what he had discovered, and the trainer countered by saying that Hans was merely “distracted” when von Osten straightened up. On one occasion von Osten even made a test by saying to Hans, “You are to count to 7; I will stand erect at 5.” He repeated the test five times, and each time Hans stopped tapping when von Osten straightened up. Despite this evidence, von Osten claimed that this was just one of Hans’s little foibles—the horse was often tricky and stubborn—and maintained that with further training the problem could be eliminated. It never was.

There have been many other clever animals. My personal favorite is Toby the Sapient Pig (

fig. 6.3

), but the menagerie includes Rosa the Mare of Berlin, Lady the Wonder Horse, Kepler (an English Bulldog), the Reading Pig of London, Don the Talking Dog, and lots more (Jay 1986; Rosenthal 1974; Spitz 1997). Clever Hans has a special place in the history of psychology, however, because of Pfungst’s meticulous research and the well-documented blindness of von Osten and other questioners to their influence on the horse. The Hans incident has become a byword in the psychological study of

self-fulfilling prophecy,

the tendency of people unconsciously to create what they expect of other people in social interaction (Merton 1948; Rosenthal 1974; Snyder 1981).