The Illusion of Conscious Will (33 page)

Read The Illusion of Conscious Will Online

Authors: Daniel M. Wegner

Tags: #General, #Psychology, #Cognitive Psychology, #Philosophy, #Will, #Free Will & Determinism, #Free Will and Determinism

It is quite possible that in daily life each of us cues others to behave in the ways we hope or expect or even guess they will behave while we also then overlook our causal contribution and attribute the behavior to them. This is particularly likely when the behavior we are performing is subtle and difficult to observe in ourselves. In the tradition of von Osten, we may miss our own fleeting smiles or anxious looks, pay no heed to our tendency to stand near one person or far from another, or not notice when we guide others with our eyes or unconscious gestures to where they should sit or what they should do. Beyond horses or other pets, we could be making many people around us “clever”—in the sense that they seem to know how to behave around us—because we are subtly cuing them to do just what we think they should. In fact, thinking that students are clever tends to make them smart, even in our absence. Rosenthal and Jacobson (1968) found that teachers who were led to expect that certain of their students would soon “bloom” came to treat the students differently (in subtle ways) and so helped the students to learn. This created improvements in the students’ actual test scores, even though the students designated as bloomers were randomly chosen by the experimenters.

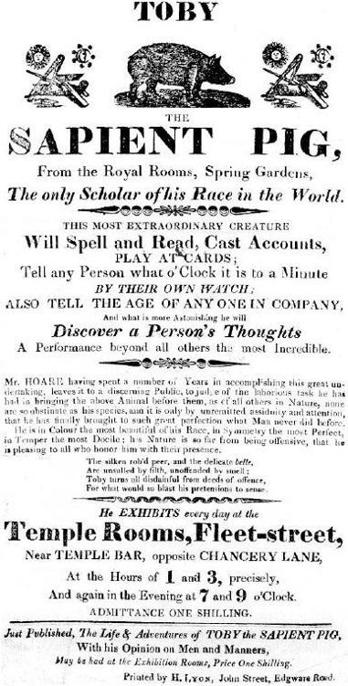

Figure 6.3

A flyer advertising the feats of one Toby the Sapient Pig, London, 1817. From Jay (1986).

The most noteworthy and insidious process of self-fulfilling prophecy occurs when we expect others to be hostile and unpleasant. We may then launch our interaction with them in such a way as to prompt the very behavior we expect. Snyder and Swann (1978) produced an illustration of this in their laboratory by giving people “noise weapons” to use in an experimental game, to be deployed if it was necessary to threaten an opponent. These weapons were no more than compressed-air boat horns, but they blasted home the point. When participants in the study were led to believe their opponent might be hostile, they used their weapons more readily. Although the opponents in this circumstance were not actually selected for hostility and instead had been randomly picked for the session, they responded to their cacophonous welcome by honking more in return. Perceived as likely to be hostile, they then actually became more hostile in the course of the game. The participants, meanwhile, were oblivious to their own roles in this transformation and merely chalked the noise up to a cranky opponent. The implications of this finding for social interaction across boundaries of race, ethnicity, or other group memberships are painfully clear. People who expect others to be hostile (merely by virtue of knowing the other’s group identification) may well produce precisely the hostility they expect through a process of action projection. Tendencies to stereotype people according to their group membership can create evidence in favor of the stereotype, quite without any preexisting truth to the stereotype.

This possibility, of course, is something of which we are sometimes aware. We know that our expectancies for an unpleasant interaction may fuel our own unpleasantness, and we thus may try to compensate for this possibility. We go overboard trying to be nice, stepping gingerly around the minefield when we expect an explosive interaction. As a result, we may have a pleasant interaction with people we expected to dislike. Research by Ickes et al. (1982) uncovered precisely this response to expectations of unpleasantness: People got along quite well in conversations with interaction partners they expected to be abrasive. The research also yielded a further result: When the interaction was over, the person who expected it to go poorly—and who therefore had worked hard to make it go well—was likely to continue to believe that the other person (who was originally thought to be unpleasant) remained unpleasant at heart. The pleasantness of

this

interaction is attributed to the self rather than to the partner, and thus nothing is learned about the partner’s true inclination one way or the other. When people go to extra lengths to compensate for the expected behavior of others, they appreciate their own influence on what others have done. Without such compensation, they often seem oblivious of the degree to which they cause the very actions they attribute to the people with whom they interact.

Clever Hands

The projection of action to Clever Hans seems to have occurred because the trainer’s actions themselves were unconsciously produced. Hans’s master overlooked his own contribution to the horse’s behavior because of its very subtlety. You have to wonder whether this level of action projection would still occur if people were conscious of their own behavior. But you don’t have to wonder for long. An extraordinary example of just such action projection has been observed all over the world—the phenomenon of

facilitated communication

(FC). This form of action projection was introduced when, in the mid-seventies, the Australian teacher Rosemary Crossley started using a manual procedure in the hope of communicating with people with autism, cerebral palsy, or other disorders that hamper speech.

The idea was for a trained facilitator to sit with the impaired client and hold his or her hand at a computer keyboard or letter board. The facilitator would keep the client “on task” and help to support the pointing or typing finger and guide the retraction of the arm. The facilitator was not to guide the client’s responses explicitly or implicitly, and facilitators were cautioned not to influence the client’s responses themselves. The result? With such facilitation, it was often found that individuals who had never said a word in their lives were quickly able to communicate, typing out meaningful sentences and even lengthy reports (Crossley 1992; Crossley and McDonald 1980). An early article on this phenomenon was even entitled with a facilitated quote: “I AM NOT A UTISTIC OH THJE TYP” [I am not autistic on the typewriter] (Biklen et al. 1991).

Many FC clients have little or no speech at all. There may be some with

echolalia

(repeating what others say), or with the ability to give stereotypical greetings or farewells. Most for whom the technique is used have had no training in any aspect of written language. They may type at the keyboard during facilitation without even looking at it. The level of language ability observed in some facilitated communications, nonetheless, is simply astounding. Beyond simple letters to parents or requests or questions to the facilitator, communications are often correctly spelled, grammatical, intelligent, and even touching. In one case, a fourteen-year-old boy who does not speak, and who often paces back and forth, slaps tables, bites at the base of his thumbs, flicks his fingers, and does not attend to people who talk to him, communicated the following with facilitation as part of a poetry workshop (Biklen et al. 1992, 16):

DO YOU HEATR NOISE IN YOUR HEAD?

IT PONDS AND SCREECHES

LIKEA TRAIN RUMBINGF THROJGH YOUR EARS

DO YUOU HEAR NOIXSE IN YOUR HEAD?

DO YOU SEE COLORS

SSWILING TWIXSTIBNG STABBING AT YOUJ

LIKE CUTS ON A MOVIE SCREEN HURLING AT YOU

DO YOU SEE CO,LORS?

DO YOU FEEL PAIN

IIT INVADES EVERHY CELL

LIKE AN ENEMY UNWANTED

DO YOU FEEL PAIN?

Such communications seem utterly miraculous. And, accordingly, there were skeptics from the start who wondered just how this kind of material could arise from the authors to whom it is attributed. The focus of suspicion, of course, was on the facilitators. The possible parallel with Ouija board spelling is not easy to overlook (Dillon 1993). But the facilitators have been among the strongest advocates of the technique and as a group have not only dismissed the idea that they might be the source of the communication but even argued heatedly against this possibility. Indeed, it doesn’t take much experience with facilitation for a person to become quite thoroughly convinced of the effectiveness of the technique (Burgess et al. 1998; Twachtman-Cullen 1997), and in one case we even find a facilitated message that addresses the doubters: “I AM REALLY DOING IT MYSELF. YOU HAVE TO TELL THE WORLD SO MORE AUY. AUTIASTIC PEOPLE CAN COMMUNICATE” (Biklen et al. 1992, 14).

The scientific examination of FC was prompted when legal challenges arose to the use of FC as a technique for delivering testimony in court (Gorman 1999). Otherwise uncommunicative clients made accusations of sexual abuse against their family members, for example, and did so only through FC (e.g., Siegel 1995). Subjected to intense scrutiny, the clever hands of facilitated communication were found to operate by much the same process as Clever Hans. There is now extensive evidence that the “communicative” responses actually originate with the facilitators themselves (Felce 1994; Jacobson, Mulick, and Schwartz 1995).

One telling study, for example, issued separate questions to facilitators and clients (by means of headphones), and all the resulting answers were found to match the questions given the facilitators, not the clients (Wheeler et al. 1993). In other studies, communicator clients were given messages or shown pictures or objects with their facilitators absent; during subsequent facilitated communication, clients were not able to describe these items (Crewes et al. 1995; Hirshoren and Gregory 1995; Klewe 1993; Montee, Miltenberger, and Wittrock 1995; Regal, Rooney, and Wandas 1994; Szempruch and Jacobson 1993). Yet other research has found that personal information about the client unknown to the facilitator was not discerned through facilitated communication (Siegel 1995; Simpson and Myles 1995) and that factual information unknown to the facilitator was also unavailable through facilitated communication (Cabay 1994). Although some proponents of facilitated communication continue to attest to its effectiveness even in the face of such evidence (e.g., Biklen and Cardinal 1997), the overwhelming balance of research evidence at this time indicates that facilitated communication consists solely of communication from the facilitator.

1

1.

The recommendations on facilitated communication made by a variety of professional organizations can be found at <

http://www.autism-society.org/

>.

All of this has been very hard to bear for the families and supporters of people with communication disorders. The curtain drew open for a short time; just briefly it seemed that it was possible to communicate with loved ones who before this had been inert, mere shadows of people. But then the curtain drew shut again as the scientific evidence accrued to show that facilitation was in fact communicating nothing. This was a personal tragedy for the victims of communication disorders and for those around them. Yet at the same time, this movement and its denouement have brought to light a fascinating psychological question: Why would a person serving as the facilitator in this situation fail to recognize his or her own active contribution? This is an example of action projection

par excellence

.

It seems remarkable indeed that someone can perform a complex, lengthy, and highly meaningful action—one that is far more conscious and intentional than the unconscious nods of von Osten to Hans—and yet mistake this performance for the action of someone else. Yet this is the convincing impression reported by hundreds of people who have served as facilitators, and it seems unlikely that such a large population would be feigning this effect. Facilitators with only a modicum of training, and with little apparently to gain from the production of bogus communications, have nonetheless become completely persuaded that their own extended keyboard performances are in fact emerging from the silent person on whose behalf they are attempting to communicate. How does such action projection occur?

There seem to be two required elements for the effect. First, action projection could only occur if people had an essential inability to perceive directly personal causation of their own actions. If we always knew everything we did—because the thought of what we did was so fundamental to the causation of the action that it simply could not be unknown—then action projection would be impossible. The effect depends on the fact that people attempting facilitation are not

intrinsically informed

about the authorship of their own action. The second element needed for action projection is the inclination to attribute such orphaned action to another plausible source, for instance, the person on whose behalf we are trying to act. Because of the basic sense in which we do know what we are doing, our behaviors are unanchored, available for ascription to others who might plausibly be their sources. The general tendency to ascribe actions to agents leads us, then, to find agency in others for actions we have performed when the origins of those actions in ourselves are too obscure to discern. The two parts of action projection, in sum, can be described as

conscious will loss

and

attribution to outside agency.

Several of the major causes of a loss of conscious will have been the topic of our prior discussions. We’ve looked in particular at how reduced perceptions of the priority, consistency, and exclusivity of thought about action can undermine the experience of will, and it follows that these factors are important here as well. People may lose the sense of conscious will when they fail to notice the apparent causal role of their thoughts. This can happen because the thoughts are not salient in mind just prior to the action, when the consistency of the thoughts with the action goes unnoticed, or if there are other competing causes that suggest the thoughts are not the exclusive cause of the action.