The Illusion of Conscious Will (36 page)

Read The Illusion of Conscious Will Online

Authors: Daniel M. Wegner

Tags: #General, #Psychology, #Cognitive Psychology, #Philosophy, #Will, #Free Will & Determinism, #Free Will and Determinism

When the leaders got off the hot line, they were given the task of retrieving the interaction from memory by recalling what statement was made before and after each of several cue statements. Memory for the interaction was influenced by the set each “leader” had been given. Those prompted to think defensively remembered their own statements that

followed

the statements of their partner but not their own statements that

preceded

the statements of their partner. As compared to a control group given no instructional set, these defensive-set participants apparently punctuated the interaction in such a way as to see the other person as causal. The participants given an offensive set, however, showed no memory punctuation effect compared with the participants given no special set. The experimenters concluded that it may be difficult to enhance the degree to which people remember themselves as causal in an interaction by means of an instructional set. Recalling self as the initiator might already be the default setting, as it were.

For the defensive-set people in this study, there is something quite like action projection going on. As in the cases of Clever Hans and FC, people in this situation are not accepting authorship of the behavior that their bodies are nevertheless causing. The attribution of one’s action to the other person—seeing one’s action as a response rather than as an initiation—has the same formal properties as the attribution of one’s action to a horse or to a person who cannot communicate at all. When people are set to think of their behavior as a reaction to the behavior of others—whether as a defensive set, as a matter of facilitation, or as some other form of helpful sensitivity to the other’s actions—they can become oblivious to their own causal role in prompting the other to behave and instead perceive the other as the willful agent of the behaviors the other has been forced or obligated to perform.

Projecting one’s own action to others is not, it turns out, a rare or abnormal event. People can mistake their own actions for those of others in a variety of contexts and with a fairly high degree of regularity. The main ingredient that gets this started is the simple belief that the other may be the agent of the action. Because the task of attributing authorship is dauntingly difficult even in some of the most apparently straightforward social settings, the moment-to-moment assignment of authorship can veer quite far away from reality. We can pin “whodunit” on anyone, even the butler who is locked in the cellar. The presence of other social agents makes available an important source of nonexclusivity and thus undermines the perception of own conscious will for one’s actions. The tendency to project action to others, in this light, is produced by our inclination to focus on the causal properties of the other people. When we focus on another mind in great depth, we neglect to consider the causal status of our own thoughts. Instead, we may read most everything that happens in an interaction in terms of what it says about the other’s mental state, inclinations, and desires. In a way, we lose ourselves in the other person. The tendency to simplify the computation of will by focusing on another person while ignoring the self can oversimplify and blind us to what we are doing.

And We Makes Three

Assuming that one person is in control is not the only way to solve the whodunit of will in interactions. There is yet another wrinkle in will computation that is introduced by the human proclivity to think of groups as agents. When you and I go to the beach for an afternoon, for instance, it is often true that each of us will think about what

we

are going to do rather than what I am going to do or what you are going to do. The reclassification of the two individuals into a co-acting entity serves to reduce the overall concern with just who is influencing whom within the group and focuses instead on our joint venture. We do things, stuff happens to us, and then we come home all sandy. The beach trip will always be ours.

This invention of the group agent can reduce the number of author-ships each person needs to think about and remember. Keeping track of which person did what becomes unnecessary, and indeed somewhat divisive and insulting, when people are joined in a co-acting group. Families, couples, school classes, office co-workers, political liaisons, and many other groups become “we,” occasionally just for moments but at other times in a rhythm that recurs throughout life. This we-feeling was noted early in the history of the social sciences by C. H. Cooley (1902), who described some of the circumstances that can give rise to this trans-formation in the individual’s state of mind. He remarked that although there are many bases for categorizing people into groups (Campbell 1958; Heider 1958), the most dramatic changes in perception seem to happen when people come to understand that they are part of a group attempting to reach a common goal.

The change to “we” as the accounting unit for action and will is marked quite clearly by the use of the word in everyday language. People say “we went to the park” to indicate not only the motion of more than one body but also that a group goal was formed and achieved. The “we” becomes an agent, coalescing from individuals at least once to select and attain the group goal, and at this time the individuals all refer to their (individual) action as something “we” did. The “we” is a convenient ghost, a creature born just briefly for the purpose of accounting for the action of this collective, which may pass away just as quickly if no more group goals are set (Wegner and Giuliano 1980).

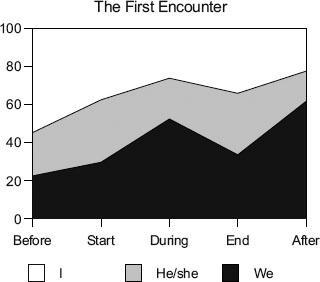

The quicksilver formation and dissipation of the “we” can be tracked over time in the stories people tell about what they have done with their friends and intimates. In a study of such intimate episodes, Wegner (1982) asked college students to write accounts of a series of different events, such as when they first met their partner, a time when their partner went away for a while, and so on. Participants were to write about each episode in five segments: beforehand, when it started, during the episode, as it ended, and after it was over. The pronouns people used throughout the narratives were counted, and the births and deaths of many a “we” were thus rendered in statistical detail.

Watch what happens to the pronouns in this, a typical story of a first encounter: “I was going to the dance just to hang out and saw him a couple of times early in the evening. I liked his smile, and he seemed to be looking at me whenever I looked over there. Then he was gone for a long time and I worried that I would never meet him. But he showed up and asked me to dance. We danced once and it was really short before the band took a break, and then he asked if we could dance together a whole lot more, and I couldn’t help but giggle at him. We stood and talked and then kept on dancing later, and my friends were pointing at us and waving at me. We went in the hall and talked and then walked home together. Since then we’ve been seeing each other pretty much every day.”

Figure 6.5

Proportions of personal pronouns at five points in narratives of a first encounter with a person who subsequently became a close friend. From Wegner (1982).

The transition from

I

and

he

early in this episode to the predominance of

we

later mirrors the overall trend for many stories of such episodes (

fig. 6.5

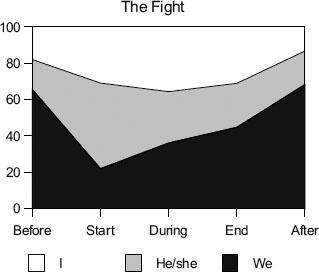

). Other episodes, in turn, revealed different patterns. When the partner goes away for a while,

we

begins the episode, wanes in the middle, and then returns at the end. The same thing happens when self and partner go through a fight (

fig. 6.6

). When the person meets a friend by chance on the street,

we

appears only at the meeting and then dissipates when the person returns to individual activities. When one person helps another,

we

forms during the incident as well. However, when a person happens to meet an enemy, there is very little mention of

we

at any point in the description of the episode.

The formation of the “we” can reduce the awareness of self and other as individual social entities. There is a decrease in the use of the pronoun

I

by individuals in a group, for example, as the size of their group increases (Mullen, Chapman, and Peaugh 1989). This process has been called

deindividuation

(Festinger, Schacter, and Back 1950; Zimbardo 1970) and has been implicated in the reduction of personal responsibility and morality that comes with the immersion of individuals in crowds and active groups. Children who trick-or-treat in large groups, for example, are more likely to snitch extra candy from an untended bowl than are children who do so in smaller groups (Diener, et al. 1976). Such snitching is but a minor example of the kinds of mayhem that accrue when people get together in groups—from suicide-baiting crowds (“Jump! Jump!”) to rioting rock concert audiences to angry mobs and warring clans. The loss of self-awareness in such groups makes individuals less inclined to focus on themselves as responsible agents and so yields disinhibition of immoral impulses (Diener 1979; Wegner and Schaefer 1978).

Figure 6.6

Proportions of personal pronouns at five points in narratives of a fight with a close friend. From Wegner (1982).

In a way, it seems as though the conscious will of the self is replaced by the conscious will of the group. Perhaps the will of the group is experienced by each person through a process much like the one whereby individual conscious will is experienced. The thoughts that are attributed in common to the

group

are understood as potentially causing the

group’s

actions. The group negotiates what its intentions are and observes itself acting, and individuals link these intents and acts through the principles of priority, consistency, and exclusivity to constitute their experience of a group will. Members of a couple who are planning to go out to dinner, for instance, might achieve a group intention that is not easily attributable to either individual. Thus, the couple may do something that it (the “we”) alone has willed. He suggests seafood, she mentions the Mexican place, and “we” eventually settle on a candlelit dinner at the Cabbage Hut. This is uniquely a group choice, in part because it was not the first choice for either individual, and so can be something that helps to define the “we” and set it in motion as an independent agent (Wegner, Giuliano, and Hertel 1985).

The “we” can also turn company into a crowd. When people encounter situations in which intention and will are difficult to discern, the existence of this further entity creates new partitions of the will that can complicate further any understanding of who caused what. Consider this exercise in pronouns: When “he” accuses “her” of not doing the right thing for “us,” and “she” says that “we” have never acted so distant from each “other” before, and “they” then go to separate rooms and sulk even though “he” wants to make up with “her”—the skein of wills is difficult indeed to unravel. A person may feel one conscious will identified with the self and yet a different one identified with the group of which self is a member. Serious internal conflicts and mixed feelings can result. The basketball player who wants her team to win but wants her rival on the same team to fall into a hole, for example, is likely to experience an ambivalent sense of accomplishment with either the winning or the falling.

Does group will count as action projection? In the cases of individual action projection we have reviewed, one person does something and perceives that action as having emanated from another person (or animal). It may be that similarly, in performing group actions, the individual in a group may well do something and yet perceive that action as having emanated from the group. In some cases, of course, the individual’s intent may clearly coincide with the group’s intent, and it may thus be quite reasonable for the individual to claim that the self’s action was actually that of the group. In other cases, however, the individual may intend and do something that the group does not intend or do. Yet, if the individual simply misperceives the intention as belonging to the group, then anything the individual does can be ascribed to the group. The formation of a “we,” then, can be a basis for doing acts on behalf of the remainder of the group that are in fact generated solely by the self.