The King's Speech (22 page)

Authors: Mark Logue,Peter Conradi

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #General, #History, #Modern, #20th Century, #Royalty

The King and Queen set off for home on 15 June from Halifax, aboard the liner

Empress of Britain

. There was no doubting the importance of the contribution the visit had made not just to Britain’s relationship with the New World, but also to the King’s own self-esteem – a point noted by the press on both sides of the Atlantic. ‘The trip nowhere had more influence than on George VI himself,’ noted

Time

four days later. ‘Two years ago he took on his job at a few hours’ notice, having expected to play a quiet younger brother role to brother Edward all his life. Pressmen who followed him around the long loop from Quebec to Halifax were struck by the added poise and self-confidence that George drew from the ordeal.’

The theme was picked up later by the King’s official biographer. The trip ‘had taken him out of himself, had opened up for him wider horizons and introduced him to new ideas’, he noted. ‘It marked the end of his apprenticeship as a monarch, and gave him self-confidence and assurance.’

78

This self-confidence had been reflected in the speeches that the King had made during the visit. ‘I have never heard the King – or indeed few other people – speak so effectively, or so movingly,’ Lascelles wrote to Mackenzie King, the Canadian prime minister. ‘One or two passages obviously stirred him so deeply that I feared he might break down. This spontaneous feeling heightened the force of the speech considerably . . . The last few weeks, culminating in his final effort today, have definitely established him as a first-class public speaker.’

79

The King’s British subjects had a chance to appreciate his newfound confidence at a lunch at the Guildhall on Friday 23 June, the day after he and the Queen returned to London to a tumultuous welcome. The King had cabled Logue from the ship to be at the Palace at 11.15. He arrived early enough to have a brief word with Hardinge, who told him the King was tired but in great form.

As always, the King seemed a little nervous to Logue, but he soon relaxed and broke into his characteristic grin as they spent a couple of minutes talking about the trip. ‘He was most interested in Roosevelt – a most delightful man he called him,’ Logue wrote. They ran through the speech, which Logue thought too long; as ever straying beyond the mere words to the content itself, he also made clear his belief that it should contain more references to the American part of the trip. The King noted his advice, but with the speech due to be delivered only a few hours later, it was a bit late for either of them to do anything about it.

Some seven hundred of the great and good were invited to the Guildhall, where they were treated to an eight-course lunch, washed down with two brands of 1928 champagne and vintage port. ‘It is a great pity that a colour film was not made of the scene,’ commented the

Daily Express.

‘It would have preserved for posterity a close-up of the entire executive power of Britain, tightly packed on a few square yards of blue carpet.’

Speaking with great emotion, the King described how the visit had underlined the strength of links between Britain and Canada. ‘I saw everywhere not only the mere symbol of the British Crown; I saw also, flourishing strongly as they do here, the institutions which have developed, century after century, beneath the aegis of that Crown,’ he told his audience, who interrupted him several times with loud cheers.

Logue, who listened to the speech on the radio, was impressed. Lascelles called him at 4.15 ‘to say how pleased everyone was with the speech,

particularly the King

’.

The verdict of the press was also positive. The

Daily Express

’s William Hickey column described it as ‘an admirable, shapely speech’ with personal touches that gave the impression the King had composed it himself. It was well delivered, too. ‘The King has improved so enormously in this respect since the early days of his reign that one is not now conscious of any impediment,’ the newspaper noted, adding that he had developed the orator’s art of leaving just enough time for the loud cheers that punctuated his speech.

The following month the King expressed his own reaction to the growing praise for his skills as an orator in his reply to a letter of congratulation from his old friend Sir Louis Greig. ‘It was a change from the old days when speaking, I felt, was “hell”,’ he wrote.

80

CHAPTER TWELVE

‘Kill the Austrian House Painter’

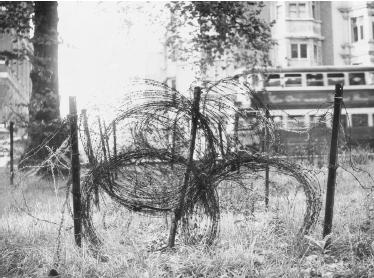

Green Park took on a very different aspect during World War Two

O

n the morning of Sunday 3 September 1939 the inevitable finally happened: Sir Nevile Henderson, the British ambassador to Berlin, delivered a final note to the German government stating that unless the country withdrew the troops it had sent into Poland two days earlier by eleven o’clock that day, Britain would declare war. No such undertaking was given, and at 11.15 Neville Chamberlain went on the radio to announce, in sorrowful and heartfelt tones, that Britain was now at war with Germany. France followed suit a few hours later.

The House of Commons met on a Sunday for the first time in its history to hear Chamberlain’s report. One of the prime minister’s first acts was a reshuffle that brought Winston Churchill back into government as First Lord of the Admiralty, the post he had held during the First World War. Anthony Eden, who had resigned in protest over the prime minister’s policy of appeasement in February 1938, returned as secretary for the dominions. Chamberlain was now seventy years of age and already suffering from the cancer that would kill him little more than a year later – but not before he had been forced to resign, ceding the premiership to Churchill who was five years his junior.

There had been a feeling throughout that sweltering summer that war was imminent. The announcement on 22 August of a non-aggression pact between Germany and the Soviet Union brought the conflict one step closer, by giving Hitler a free hand to invade Poland and then turn his forces on the West. Three days later, Britain signed a treaty with the government in Warsaw pledging to come to its assistance if it were attacked. Chamberlain nevertheless continued to negotiate with Hitler, even though he turned down the King’s offer to write a personal letter to the Nazi leader. For many people, the worst thing was the uncertainty.

On 28 August Logue was summoned to the Palace. Alexander Hardinge, exceptionally, was there in his shirtsleeves. It was uncomfortably hot – the kind of weather Logue would have expected back home in Australia rather than in his adoptive nation. ‘One of the most stifling and unpleasant days that I can ever remember, reminded me more of Sydney or Ceylon than any day in England,’ he wrote in his diary.

The King and his aides seemed as frustrated as everyone else in the country about the lack of resolution of the crisis – as Logue noted. ‘I went into the King and his first words were “Hello Logue, can you tell me, are we at war?”’ he wrote. ‘I said I didn’t know and he said, “You don’t know, the Prime Minister doesn’t know, and I don’t know.” He is greatly worried, and said the whole thing is so damned unreal. If we only knew which way it was going to be.’ By the time Logue went home, however, he was convinced that ‘war is just around the corner’.

Then, on 1 September, German troops moved into Poland. ‘Britain Gives Last Warning,’ screamed the front page headline of the

Daily Express

the following morning. ‘Either stop hostilities and withdraw German troops from Poland or we will go to war.’ The smaller sub-headline immediately below provided the answer: ‘An ultimatum we will reject, says Berlin.’

Over the last few months the government had been preparing Britain and its civilian population for war – and what was expected to be heavy bombing of its major cities. Some 827,000 schoolchildren were evacuated to the country, alongside just over 100,000 teachers and their helpers, from London and other urban areas. A further 524,000 children below school age left with their mothers. The cities themselves were protected with air-raid sirens and barrage balloons; windows were to be covered with black-out paper. Trenches were dug in parks and air-raid shelters. Those with gardens of their own dug holes in which they erected corrugated-iron Anderson shelters, covering the structure over with the earth they had removed. It was recommended they dig down at least three feet.

One of the greatest fears was of chemical warfare. Poison gas had been used to horrific effect in the trenches during the First World War and there was concern that the Germans might use it against civilians in this conflict. By the outbreak of war, some 38 million black rubber gas masks had been handed out, accompanied by a propaganda campaign. ‘Hitler will send no warning – so always carry your gas mask,’ read one advertisement. Those caught without one risked a fine.

The Logues, like everyone else, were preparing for the worst. Starting on the night of 1 September, street lights were turned off and everyone had to cover up their windows at night to make it more difficult for German bombers to find their targets. Tony, their youngest, an athletic young man with wavy brown hair who was soon to celebrate his nineteenth birthday, came back from the local library bearing a sheet of black-out paper and embarked on making all the windows lightproof. Fortunately all the main rooms had shutters – Myrtle hated them and had long contemplated ripping them out but was now rather glad she hadn’t.

There wasn’t enough black-out paper to do all the windows so Tony had left one uncovered in the bathroom. It didn’t seem much of a concern but that evening, a few minutes after Myrtle went in to clean her teeth before going to bed, there was a knock on the front door. She opened it to two air-raid precaution wardens who told her in courteous tones that she should turn out the light. Sleeping in a blacked-out room was also an unfamiliar experience: Myrtle felt like a ‘chrysalis in a cocoon of semi-gloom’.

The family had a more immediate problem: Therese, their devoted cook, who had lived in London for the previous ten years, was originally from Bavaria. ‘Oh Madam, I am caught – it is too late to get away,’ she told Myrtle, tears streaming down her cheeks. That afternoon they had turned on the radio, only to hear an alarming notice of general mobilization. Therese rang the German embassy and was told there was a last train leaving at ten o’clock the next morning, and she rushed away to pack.

In the Logue household, as elsewhere in the country, the sense of apprehension was leavened by some lighter moments. ‘The charwoman turned a tense situation into one of great comedy,’ Logue recalled. ‘Her boy Ernie was taken to the country yesterday, and as she went downstairs she said “Thank God my Ernie has been excavated.’”

However unwelcome the prospect of fighting another war, only just over two decades after the end of the last one, Chamberlain’s declaration of 3 September meant the people of Britain at least now knew where they stood. ‘A marvellous relief after all our tension,’ wrote Logue. ‘The universal desire is to kill the Austrian house painter.’ The King expressed similar sentiments in his own diary, which he was to keep dutifully for the next seven and a half years. ‘As eleven o’clock struck that fateful morning I had a certain feeling of relief that those 10 anxious days of intensive negotiations with Germany over Poland, which at moments looked favourable, with Mussolini working for peace as well, were over,’ he wrote.

81

Myrtle, meanwhile, was preoccupied with more practical matters: she made 10lb of damson jam and 8lb of beans to salt down. War or no war, they had to eat. Laurie and his wife Josephine – or Jo, as she was known in the family – were also there. Myrtle was worried about them: Jo was expecting their first child (Lionel and Myrtle’s first grandchild) at the end of that month. As Myrtle wrote in the diary that she was now keeping, she hoped that Jo would be ‘excavated’ too.

A few minutes after Chamberlain had finished speaking, the unfamiliar wail of air-raid sirens could be heard across London. Logue called Tony, who was in the garage mending his bicycle, and they began to close all the shutters. From their window they could see the barrage balloon going up – it was, Logue noted, a ‘wonderful sight’. A few miles away in Buckingham Palace, the King and Queen were also surprised to hear the ghastly wailing of the sirens. The two of them looked at each other and said, ‘it can’t be’. But it was, and with their hearts beating hard they went down to the shelter in the basement. There, in the Queen’s words, they ‘felt stunned & horrified, and sat waiting for bombs to fall’.

82

There were no bombs that particular night, and about half an hour later the all-clear went up. The royal couple, like others fortunate enough to have access to a shelter, returned to their homes. It was to be the first of many such false alarms as the much feared air raids on London were not to start in earnest until the Blitz almost exactly a year later.

The first night of the war started like any other. The only difference Myrtle noticed was there were no programmes on the radio; they just played records. Then at 3 a.m. came another air-raid warning and they hurried down to the stuffy basement. ‘The only feeling is one of irritation,’ she wrote in her diary. ‘It is strange how things work out – no panic, no fear only plain mad at being disturbed.’