The Mayor of MacDougal Street (22 page)

Read The Mayor of MacDougal Street Online

Authors: Dave Van Ronk

Times A-Changing:

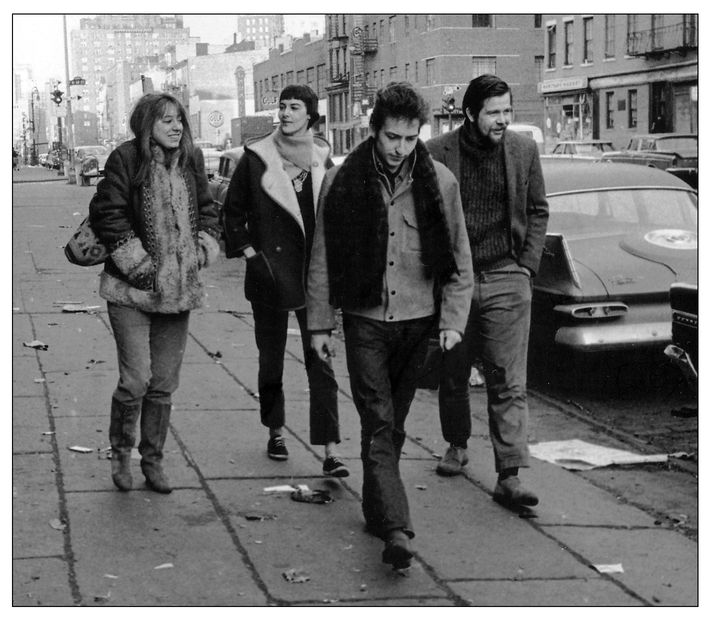

On the street with Suze Rotolo, Terri Thal/Van Ronk, and Bob Dylan

(photo: Jim Marshall)

; going electric with The Hudson Dusters: Phil Namanworth, Dave Woods, Rick Henderson, and Ed Gregory.

On the street with Suze Rotolo, Terri Thal/Van Ronk, and Bob Dylan

(photo: Jim Marshall)

; going electric with The Hudson Dusters: Phil Namanworth, Dave Woods, Rick Henderson, and Ed Gregory.

I have already mentioned the degree to which we wanted to distance ourselves from the whole beatnik craze, but people who were not around at that time may have a hard time understanding what it was like. There were some smart, talented people who are, in retrospect, considered “beats,” and they shared a lot of the same tastes as my friends and I: they were well-read, knew a lot about jazz, and some of them were pretty deeply into politics, at least on the arguing level. On the other hand, there were the beatniks, who were much the same sort of self-conscious young bores who twenty years later were dying their hair green and putting safety pins in their cheeks. We despised them, and even more than that we despised all the tourists who were coming down to the Village because they had

heard

about them. The whole beatnik thing had become a mass-media preoccupation: there were articles like “

Life

Goes to a Pot Party” and even a “Rent-a-Beatnik” service that advertised in the

Village Voice

for years. For a nominal fee, you could hire some clown to come to one of your parties in East Hampton or where have you, and this citizen would show up complete with beard, bongos, and beret—the three Bs—for the low, low price of twenty-five bucks for the evening, and wander around the party saying “Wow” and “Far out” and occasionally taking a feckless thwack at his bongo. It was a thriving little cottage industry, and a huge proportion of the audience in those coffeehouses was suburban tourists checking out the freaks.

heard

about them. The whole beatnik thing had become a mass-media preoccupation: there were articles like “

Life

Goes to a Pot Party” and even a “Rent-a-Beatnik” service that advertised in the

Village Voice

for years. For a nominal fee, you could hire some clown to come to one of your parties in East Hampton or where have you, and this citizen would show up complete with beard, bongos, and beret—the three Bs—for the low, low price of twenty-five bucks for the evening, and wander around the party saying “Wow” and “Far out” and occasionally taking a feckless thwack at his bongo. It was a thriving little cottage industry, and a huge proportion of the audience in those coffeehouses was suburban tourists checking out the freaks.

To the tourists, folk music was simply part of the beatnik scene. Actually, the beats liked cool jazz, bebop, and hard drugs and hated folk music, which to them was all these fresh-faced kids sitting around on the floor and singing songs of the oppressed masses. When a folksinger would take the stage between two beat poets, all the finger-poppin’ mamas and daddies would do everything but hold their noses. Then, when the beat poets would get up and begin to rant, all the folk fans would do likewise. But in the eyes of the media, folk music and beatniks were one and the same.

In 1959 the poets still had very much the upper hand. I sometimes say, and there is more than a little truth to it, that the only reason they had folksingers in those coffeehouses at all was to turn the house. The Gaslight seated only 110 customers, and on weekend nights, there would often be a line of people waiting to get in. To maximize profits, Mitchell needed a way to clear out the current crowd after they had finished their cup of overpriced

coffee, since no one would have bought a second cup of that slop. This presented a logistical problem to which the folksingers were the solution: you would get up and sing three songs, and if at the end of those three songs anybody was still left in the room, you were fired.

coffee, since no one would have bought a second cup of that slop. This presented a logistical problem to which the folksingers were the solution: you would get up and sing three songs, and if at the end of those three songs anybody was still left in the room, you were fired.

Over the next year or two, though, the situation changed completely. I am reminded of the old tale of the Arab and the camel: An Arab is in his nice, snug, warm tent in the desert on a freezing cold night, and a camel sticks his head in and says, “Do you mind if I just put my nose inside the tent to get it warm? It’s really freezing out here.” The Arab, being a soft-hearted fellow, says, “Go on, be my guest.” The camel sticks his nose in, but after a while he pipes up again, saying, “Do you mind if I just put my ears in as well?” The Arab allows this as well, and the story goes on and on until finally the Arab is freezing out on the desert and the camel is warm inside the tent. Thus it was with the folksingers and the beat poets. The poor bastards never knew what hit ’em.

Basically, it turned out that we could draw larger crowds and keep them coming back more regularly. This was not because folk music is inherently more interesting than poetry, but singing is inherently theatrical, and poetry is not. Even a very good poet is not necessarily any kind of a performer, since poetry is by its nature introspective—“In my craft or sullen art / Exercised in the still night,” as Dylan Thomas put it. A mediocre singer can still choose good material and make decent music, while a mediocre poet is just a bore. And some of the poets around MacDougal Street were the absolute bottom of the barrel. So gradually more and more clubs phased the poets out and the singers in. It was not an absolute changeover: even into the 1960s they would keep someone like Eddie Freeman around for those occasions when a tourist would come in and say, “Hey, you got any beatnik poets?” They had to have a token specimen, just for the look of the thing, but to all intents and purposes that craze was dead. The poets probably have a quite different take on this history—I suspect their attitude is “We never lost the ball, we just got bored with the park”—but that is how it seemed to me.

When I first got back from California, Roy was the only person I knew who was playing regularly on MacDougal—frankly, one reason I disliked the Gaslight so much was probably because he had the gig and I didn’t, and I was jealous. My turn came soon enough, though. A few months after my

return, I ran into Jimmy Gavin, who was back in New York as well, and he told me he was booking the music for a coffeehouse called the Commons. It was right across the street from the Gaslight, and I went down there on Jimmy’s invitation, and there were four or five performers working there, and I became the fifth or sixth. It was what was called a “basket house,” which meant that most of the money for performers came in the form of tips. There would be a basket at the door, supervised by a young woman who would cajole, shame, or threaten the clydes into tossing in a buck or two on their way out, and however many people performed in a night, that’s how many ways the basket would be split. On a good weekend night, you could actually make out pretty well, and the people who were regulars on the bill were also pulling a salary—only $100, $125 a week, but in 1960 you could live on that. As in LA, we worked hard for the money, because being a coffeehouse it did not have to shut down when the bars shut down, so after “last call” at 4:00 A.M., we would get our second straight rush and that would sometimes keep us working until 7:00, 8:00, 9:00 in the morning. I loved walking up 6th Avenue on my way home to bed, watching all the poor wage slaves schlepping off to work.

return, I ran into Jimmy Gavin, who was back in New York as well, and he told me he was booking the music for a coffeehouse called the Commons. It was right across the street from the Gaslight, and I went down there on Jimmy’s invitation, and there were four or five performers working there, and I became the fifth or sixth. It was what was called a “basket house,” which meant that most of the money for performers came in the form of tips. There would be a basket at the door, supervised by a young woman who would cajole, shame, or threaten the clydes into tossing in a buck or two on their way out, and however many people performed in a night, that’s how many ways the basket would be split. On a good weekend night, you could actually make out pretty well, and the people who were regulars on the bill were also pulling a salary—only $100, $125 a week, but in 1960 you could live on that. As in LA, we worked hard for the money, because being a coffeehouse it did not have to shut down when the bars shut down, so after “last call” at 4:00 A.M., we would get our second straight rush and that would sometimes keep us working until 7:00, 8:00, 9:00 in the morning. I loved walking up 6th Avenue on my way home to bed, watching all the poor wage slaves schlepping off to work.

The Commons was my professional introduction to MacDougal Street and vice versa. Pretty soon I had built up something of a regular following, and in August of 1960 the

Village Voice

did a big cover piece on me. This might not be worth noting, except for the fact that the

Voice

assiduously ignored the folk scene. There had been one short piece on Carolyn Hester a few months earlier, but in general the paper was trying to be a community weekly, and a lot of people in the community thought of the coffeehouse entertainers as outsiders, beatniks, and bait for the tourists and trouble-makers that were ruining the neighborhood. The same reporter who did the piece on me had just finished a three-part series on how MacDougal Street had become “a fruitcake ‘Inferno’,” and the beatnik equivalent of Coney Island. Thus, odd as it seems, this was not only the first cover piece on a Village folksinger but also the last. Over the next few years, which are often remembered as the high point of Greenwich Village as a musical mecca, the local press did its best to avoid the whole subject.

Village Voice

did a big cover piece on me. This might not be worth noting, except for the fact that the

Voice

assiduously ignored the folk scene. There had been one short piece on Carolyn Hester a few months earlier, but in general the paper was trying to be a community weekly, and a lot of people in the community thought of the coffeehouse entertainers as outsiders, beatniks, and bait for the tourists and trouble-makers that were ruining the neighborhood. The same reporter who did the piece on me had just finished a three-part series on how MacDougal Street had become “a fruitcake ‘Inferno’,” and the beatnik equivalent of Coney Island. Thus, odd as it seems, this was not only the first cover piece on a Village folksinger but also the last. Over the next few years, which are often remembered as the high point of Greenwich Village as a musical mecca, the local press did its best to avoid the whole subject.

The

Voice

piece was very welcome, naturally, though as with all articles of that period it laid more stress on the “white man singing the blues” angle than I cared for. It began:

Voice

piece was very welcome, naturally, though as with all articles of that period it laid more stress on the “white man singing the blues” angle than I cared for. It began:

The occasional wanderer poking around tiny Minetta Street these summer evenings is liable to meet up with a most unusual sound. It drifts from the glass-partitioned back entrance of The Commons coffee house. Now wailing, now dropping on down to a mean, guttural rasp, it is the sound of a man belting out Negro ballads and blues. The voice, however, does not quite have the timbre associated with southern Negro singing. But it is filled just the same with all that smoky, bittersweet funk and jazz common to the musical tradition south of the Mason and Dixon line.

The reporter described me as “hunched over a table, nervously dragging on a cigarette. . . . A certain weariness and the droopy bush of a blond moustache make him older than his 24 years.” After batting around the subject of my ethnicity, the reporter asked if I had spent much time in the South:

A tremendous grin breaks out under the walrus moustache. He scratches at his mop of brown hair. “Sometimes I feel like palming myself off as Homer Scragg, the banjo picker from Sawtooth, Arkansas. Actually, I’m from Brooklyn. And that low-down sound in my voice? Man, I’ve got asthma. The worse the weather, the rougher and raspier I sound. It’s great. It hides all the defects.”

The story summarized my basic bio, with some chat about the evils of southern racism and segregation, then ended with a question about my obvious musical growth since the Folkways album. The reporter suggested that I seemed to have developed a “more popular touch.” I hastened to agree:

“For years I’ve hung around Israel Young’s Folklore Center on MacDougal Street. I learned a helluva lot about ethnic music from the records and talking to the people there. Izzy, by the way, is the real unsung hero of folk music around New York. But lately I’ve been listening to other stuff—specifically Ray Charles. I think he’s the finest vocalist for jazz or country blues around today. He represents the best of the rhythm and blues. I mean, he swings. I don’t think I can go wrong learning from him.”

Then I was back onstage, singing “Careless Love.”

It was a nice piece, but I got awfully tired of that business about singing “Negro music.” Frankly, I was puzzled by all the fuss. After all, no one had ever suggested that there was anything strange about me singing like Louis Armstrong when I was doing jazz. Copying Louis’s phrasing was standard procedure for jazz singers, white and black. When I listen to my recordings, I hear an obvious debt to Louis, and on those early records to Bessie Smith, as well as to Jelly Roll Morton, Bing Crosby, Billie Holiday, and Gary Davis. Except for Gary, that is a fairly standard list that you might have heard from any jazz singer of my generation or of the generation before mine.

There was indeed a racial gap between me and the people who had originally recorded most of the material I was doing at that point, but there was also a large time gap. I was singing songs I had learned from recordings of Bessie Smith made in the 1920s, and musical fashions had changed tremendously in the intervening decades. So it was not just that young white singers were not doing anything like that; nobody had heard anything like that for thirty years except people who were into old music for nostalgic or scholarly reasons, or because they liked the music for itself as an “art form.”

When I first started getting a lot of flak, I tried to counter it as best I could, and one of my strongest debating points was that so few black musicians were still doing that material. There were Sonny and Brownie, Josh White, and very few others. Certainly nobody who was going to work for what they were paying on MacDougal Street. So I would just say, “Look, if I don’t do this music, who will?” A few years later, when Son House, John Hurt, and Lightnin’ Hopkins resurfaced and started touring around the folk clubs, that answer was no longer valid, but by then most people had stopped asking me the question.

Other books

Vanishing Act by Barbara Block

Stokers Shadow by Paul Butler

A Tale of Four Birds and Their Quest for Food and Happiness by Gramps Doodlebug

Final Vector by Allan Leverone

Man Who Loved Pride and Prejudice by Abigail Reynolds

Maggie and Max by Ellen Miles

Murder of a Chocolate-Covered Cherry by Denise Swanson

Sarah's Education by Madeline Moore

The Magus by John Fowles

Southern Haunts by Stuart Jaffe