The Modern Middle East (19 page)

Read The Modern Middle East Online

Authors: Mehran Kamrava

Tags: #Politics & Social Sciences, #Politics & Government, #International & World Politics, #Middle Eastern, #Religion & Spirituality, #History, #Middle East, #General, #Political Science, #Religion, #Islam

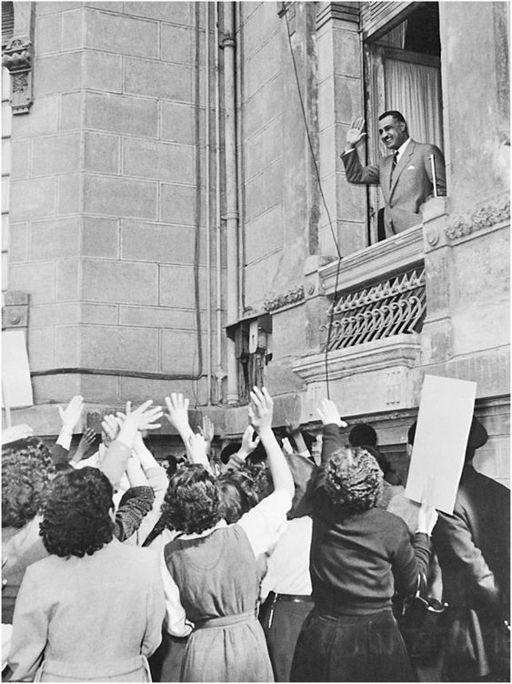

Figure 7.

Egyptian women celebrating Nasser’s announcement of women’s right to vote, 1956. Corbis.

While the ASU’s elaborate organizational structure ensured mass participation in the political process, the repressive apparatus of the state was never far from sight. The army and the security services, the dreaded

mukhaberat,

became omnipresent. They struck fear into the hearts of Nasser’s potential opponents and helped keep intact the mystiques of total power and popular adulation.

All these domestic accomplishments aside, it was in the foreign policy domain, and largely because of it, that Nasser emerged as a larger-than-life figure. Like that of his contemporaries, Nasser’s leadership was crystallizing at a time of intense military and diplomatic competition between the communist bloc and the West. To survive against domestic adversaries and potential challenges from abroad, all Middle Eastern leaders at the time—from the shah of Iran to the generals ruling in Turkey and King Hussein of Jordan, as well as the fledgling monarchies of the Arabian peninsula—had cast their lot with the West. This was represented initially by Britain’s extensive involvement in the region, and, later, beginning in the 1950s, by that of the United States. Whatever the actual wisdom of such alliances, the peoples of the Middle East often saw their leaders as Western puppets, lackeys installed by imperialism to do its dirty work. Partly out of conviction and partly to cement his populist image, Nasser became one of the main figures within the NonAligned Movement (NAM), espousing a policy of “positive neutralism” that, in theory at least, was meant to favor neither the Eastern bloc nor the West.

74

In the 1955 NAM Summit Nasser was seen as the spokesman of the Arab world and, in league with the likes of Jawaharlal Nehru and Josip Tito, its primary advocate and protector against the global forces of colonial domination.

Nasser’s actual confrontation with the West was not long in coming. For some time, Egypt’s foreign policy had featured four specific goals: securing financial support for building the Aswan Dam; acquiring military hardware

for its army; wresting control of the Suez Canal from British and French commercial interests; and clarifying the status of Sudan regarding its independence or unification with Egypt. Of these, the Sudan issue was resolved the earliest, in 1953, when the country was given the option of deciding its fate on its own through a referendum. In 1954, Sudan unilaterally declared independence.

The three remaining objectives became points of contention and, soon thereafter, conflict. In summer 1956, the United States offered Egypt financial aid for the Aswan Dam project. In an apparent move to humiliate Nasser, however, once the Egyptian president accepted the aid offer, it was withdrawn. In retaliation, Nasser nationalized the British-owned Suez Canal Company in July and proceeded to secure massive economic and military assistance from the Soviet bloc. With tensions at an all-time high, Israel invaded Egypt on October 29, 1956, ostensibly in retaliation for frequent raids into Israel from Egyptian territory by Palestinian fighters called the Fedayeen. The following day Britain and France warned the belligerents to cease fire; Egypt’s refusal to do so was followed by British bombing of Port Said at the mouth of the Suez and the landing of French and British troops in the Canal Zone on October 31.

For different reasons, each of the invading countries wanted to see Nasser toppled. For Britain and France, Nasser’s incendiary advocacy of Third World liberation had to be stopped before independence struggles like the ones in India and Algeria had a chance to spread elsewhere. France was especially troubled by Nasser’s generous support for the National Liberation Front in Algeria, which was directing the fight against French rule from Cairo. Israel, of course, had its own reasons to see Nasser overthrown, as his seemed the most credible and immediate threat to Israeli national security.

Ironically, it was the United States that came to Nasser’s rescue, pressing the invaders both directly and through the United Nations to withdraw from Egyptian territory. This was, of course, motivated less by the American policy makers’ love for Nasser than by their concerns over the reemergence of British and French military ascendancy in the region. A UN Emergency Force (UNEF) was set up to supervise the evacuation of foreign troops from Egypt and, once the evacuation was complete, to stand guard at the Egyptian-Israeli border. By late December 1956, the last of British and French troops left Egyptian territory, and, with great reluctance, Israel finally withdrew on March 9, 1957.

The Suez invasion was a military disaster for Egypt, exposing the shocking ease with which Israeli forces overran Egypt’s defenses and occupied

much of the Sinai and the Egyptian-administered Gaza Strip.

75

In fact, fearing more losses, Nasser had ordered his forces to retreat to save them from further British and French attacks. The Egyptian air force nevertheless inflicted some casualties on Israeli forces, and the invaders met with surprisingly heavy resistance in Port Said and other towns in the Sinai.

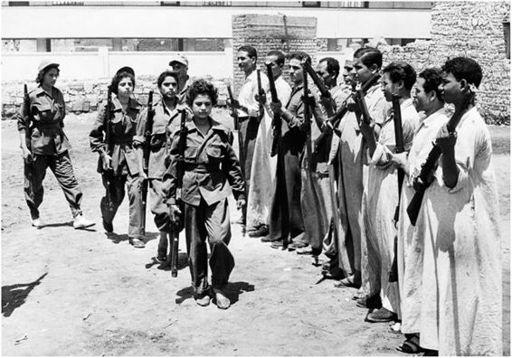

Figure 8.

Egyptian boys and girls receiving military training during the Suez Canal crisis, 1956. Corbis.

Once the dust of the invasion settled and the invaders had been forced to withdraw under international condemnation and pressure, Nasser turned is military defeat into a great diplomatic and moral victory. Such a victory, however imaginary, was just what an increasingly dictatorial, charismatic leader like Nasser needed. “I have declared in your name that we shall fight and not surrender,” he told masses of adoring Egyptians after the crisis, “that we shall not live a dishonorable life however long they persist in their aggressive plans.”

76

With his domestic enemies and potential rivals eliminated, Nasser could now delay delivering the promises of the 1952 revolution by pointing to his struggle against “Western imperialism.” Not surprisingly, after 1956 the regime turned its attention increasingly to foreign affairs, and, consequently, Nasser directed his rhetoric to an audience beyond Egypt’s borders. It was then that the phenomenon of Pan-Arabism—the process whereby the Arab nation sought to transcend

artificial, colonially drawn borders and to become one—moved beyond the realm of academia and intellectual fancy and into the realm of diplomacy and practice. And Nasser, the one Arab leader who had stared down imperialism until the latter blinked, became its chief articulator and protagonist.

For a people defeated and humiliated, for those receptive to the idea of a liberator, for the peoples of the Middle East whose leaders seemed remote and uncaring, Nasser was a hero. His fiery speeches, broadcast by Egypt’s

Voice of the Arabs,

were listened to as far away as Lebanon, Jordan, Syria, and Iraq. As with most other populist leaders, his popularity was at times greater outside Egypt than in his own country. The Egyptians feared and admired him; elsewhere in the Arab world, for the most part, he was lionized and idolized. He soon became the liberator the Palestinians never had, the voice the Arabs had yearned for, the military strongman that the times seemed to call for. Before long, in 1958, one of the most concrete steps toward Pan-Arab unity was taken when Syria and Egypt joined to form the United Arab Republic, with Nasser as its president. Arab intellectuals celebrated the birth of the UAR as a powerful synthesis of Pan-Arab ideals, and leaders elsewhere—in Yemen, Sudan, and Libya especially—sought to forge similar alliances so as not to be left behind. By the late 1950s and early 1960s, Pan-Arabism was in full swing.

Nasser’s Egyptian nationalism and before that Zionism and Palestinian nationalism were not being articulated in a historical and geographic vacuum. In fact, they were part of a continuum of nationalisms that thrived in the Arab east as far away as Iraq and in the Maghreb as far west as Morocco. Despite fundamental differences in the genesis and evolution of the nationalisms that swept across the Middle East in the early twentieth century, there were striking similarities in both their causes and their effects. In the case of Zionism, the emergence of nationalism owed much to the mobilizational efforts of early Zionist leaders and their success, over time, in combining a collective, distinct sense of Jewish identity with a viable set of statelike organizations. Once these organizations and the collective identity out of which they had arisen were transplanted onto a piece of territory, that of historic Palestine, Zionist (or Israeli) nationalism was complete. This transplantation in turn created—or re-created—a Palestinian nationalism. Egyptian nationalism was nothing new, but only after the defeat of 1948, the “catastrophe” (

nakba

), were some Egyptians prompted to take matters into their own hands and, as they saw it, redeem the honor of the Egyptian

and the larger Arab nation. Nasserism was Egyptian nationalism writ large, a reaction to military incompetence, national disgrace, and industrial and economic backwardness.

These were also the targets of Maghrebi nationalism, although here the culprit was not a domestic despot but an outside colonizer. And in this region, unlike the Arab east, it was not Britain that dominated but rather France. In each country of the Maghreb, the nature, extent, and duration of French colonialism directly influenced the emergence of nationalist sentiments and, eventually, national independence movements. This was also the case with Libya, the only country in the Maghreb, and in the entire Middle East, for that matter, that was occupied by Italy. In turn, the nature of the nationalist forces leading the movement for independence, and the way independence was achieved, had direct consequences for the politics of each of the newly independent countries.

In broad terms, Algeria’s colonial domination by France was the longest lasting and most extensive. It started in 1830, lasted for 132 years, and resulted in the transfer of 1.7 million French

colons

to Algeria, or 11 percent of Algeria’s total population. It also featured the annexation of geographic Algeria as yet another provincial administrative unit of France. By contrast, French colonial rule in Tunisia started in 1881, lasted 75 years, and resulted in less than 7 percent of the Tunisian population being made up of the

colons.

Morocco’s colonial domination was even less extensive. Begun in 1912, it lasted for only 44 years and resulted in a

colon

population of only about 5 percent.

77

Most important, in both Tunisia and Morocco, especially in the latter, existing political institutions—the

beylik

in Tunisia (a relic of Ottoman rule) and the monarchy in Morocco—were not destroyed. In fact, the “protection” of these indigenous institutions theoretically formed the raison d’être of the French protectorate. Precolonial Algerian institutions were not as fortunate. The French effectively eradicated all of them and sought to make Algeria as thorough a French possession as possible.

The Italians tried to do the same thing in Libya, but in a much shorter time span. Italian conquest of Libya started in 1911, lasted for slightly more than 30 years, and resulted in a settler population of one hundred thousand out of a total of about a million, approximately 10 percent. Only in 1951, long after the Italians were defeated in World War II and Libya’s control had been turned over to a joint British-French administration, did the country’s geographic boundaries and political structures take form under the aegis of the United Nations. Still, Libyan nationalism took nearly another two decades to emerge and make its presence felt on both the domestic and the international stages.

Morocco and Tunisia both became independent in March 1956. As we shall see presently, in each of these cases the causes and consequences of nationalism were different, although the two countries did, naturally, maintain a symbiotic relationship. In large measure, however, the French acquiesced in giving independence to Tunisia and Morocco in 1956 because they were being threatened with the loss of their much larger, older possession, Algeria. This is not to imply that Tunisian and Moroccan independence came easily. As compared to the Algerian case, however, the struggles involved very little violence. The independence movements in Morocco and Tunisia were headed by individuals and organizations that came to symbolize and articulate nationalist aspirations, thereby giving added ferocity and direction to nationalist sentiments in each country. In Morocco, the monarch, Mohammed V, emerged in this role when he opposed the French protectorate. In Tunisia, the role fell to the Neo-Destour Party and one of its most capable leaders, Habib Bourguiba. When independence eventually arrived, both the Moroccan monarch and the Tunisian Bourguiba became, in their own way, the Nassers of their respective countries.