The Other Slavery (45 page)

Authors: Andrés Reséndez

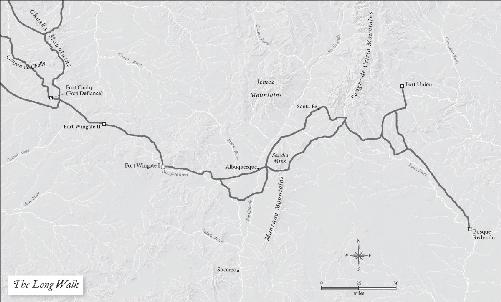

The campaign culminated in the dead of winter with the occupation of the Canyon de Chelly. Carson’s argument against entering this forbidding landscape rested on the belief that it would be better to wait “until the weather opens sufficiently to permit more extended operations.” The old scout also hoped to spend the winter with his family in Taos. General Carleton would have none of that. He prodded Carson in multiple missives, impressing on him the fact that the winter was precisely the time to ratchet up the pressure. There was little else Carson and about four hundred men could do but move into position in early January 1864. Their plan was to skirt around the canyon in order to enter it through the more distant western end. Meanwhile, veteran campaigner and former Indian subagent Albert H. Pfeiffer would enter through the east entrance with one hundred men. The two groups intended to meet at the bottom in order to cut off all the escape routes, but the plan quickly unraveled.

Rounding the Canyon de Chelly turned out to be extremely difficult. Carson’s oxen were dying every day from pulling the supply wagon through enormous heaps of snow. Although Pfeiffer entered the canyon, his mules kept breaking through the thin crust, stumbling, and falling. As Pfeiffer and his men zigzagged to the bottom, Indians appeared at every turn, jumping onto the rock ledges “like mountain cats.” In one fatal exchange, the Americans killed two Navajo males and “one squaw who obstinately persisted in hurling rocks and pieces of wood at the soldiers.” Pfeiffer covered the entire length of the canyon, about thirty miles, in

four days, and saw that thousands of Navajos had taken refuge in caves and rocks all along the canyon’s walls. The two sides for the most part kept their distance. “At the place where I encamped,” Pfeiffer wrote, “the curl of the smoke from my fires ascended to where a large body of the Indians were resting over my head, but the height was so great that the Indians did not look larger than crows, and as we were too far apart to injure each other no damage was done, except with the tongue, the articulation of which was scarcely audible.”

37

On January 14, Carson’s command finally made its way to the bottom of the canyon and caught up with Pfeiffer’s company. As the old scout put it, “We have shown the Indians that in no place, however formidable or inaccessible, are they safe from the pursuit of the troops of this command.” General Carleton was even more bombastic: “This is the first time any troops, whether when the country belonged to Mexico or since we acquired it, have been able to pass through the Cañon de Chelly which, for its great depth, its length, its perpendicular walls, and its labyrinthine character, has been regarded by eminent geologists as the most remarkable of any ‘fissure’ (for such it is held to be) upon the face of the globe.”

38

During Pfeiffer’s march across the canyon, nineteen Indians on the brink of starvation had turned themselves in. Carson’s orders were to send them to the Bosque Redondo reservation. Instead, he gave them food and turned them loose to spread the message that the Americans were not waging a “war of extermination” and that the Diné would be well treated if they accepted relocation to eastern New Mexico. Indeed, during his brief stay in the Canyon de Chelly, Carson did everything possible to persuade the Navajos that the government’s intentions were “eminently humane and dictated by an earnest desire to promote their welfare.” It was a shrewd decision. After having spent months on the run and suffered starvation throughout the winter, many Navajos received this proposal with newfound interest. And there was one additional consideration: following in the Americans’ footsteps, Utes began appearing in the canyon. They were reportedly “on the loose, riding horseback, and were dangerously aggressive.”

39

Carson’s tactic worked. By the end of January, five hundred Navajos

had surrendered. This trickle became a tidal wave within weeks, reaching five thousand by the end of March, thus surpassing even the most wildly optimistic projections and overwhelming the army’s capacity to feed and transport so many Indians. The U.S. troops turned their attention to addressing this monumental logistical challenge. But while U.S. soldiers ceased all hostilities, Hispanic and Indian bands, sensing an unprecedented opportunity to finish off their enemies, pressed their attack.

40

As the snow began to melt and Navajo families tried to surrender, bands of Hispanic and Indian volunteers took to the field. Several attacks occurred over a one-week period in late April and early May. On April 29, a distraught Navajo man arrived at Fort Canby (as Fort Defiance was now called) to report that he and his family had been intercepted by a party of Mexicans while en route to the fort to surrender. He stated that “all of his family had been either killed or captured and his herds taken by the Mexicans.” Other survivors confirmed the incident. A U.S. officer heard these testimonies and filed a report, offering one final and extremely insightful observation: “The Mexicans, Utes, Zuni, & Moqui Indians are aware that the wealthy Navajos are about to come in for the purpose of emigration to the Bosque Redondo, and take advantage of the fact and prosecute a war against them knowing that the Navajos are unprepared and are relying on the protection of the Gov’t.”

41

Another attack occurred three days later, this one against Navajos who were under the nominal protection of U.S. troops. This group had already surrendered and was on its way to Bosque Redondo, passing through the vicinity of Albuquerque, when some of its members became ill and fell behind. As the leader of the Americans, Captain Francis McCabe, did not wish to delay the rest of the column, he decided to leave the ill Navajos in charge of a petty chief with sufficient provisions. They were resting when “6 Mexicans came from the town and took 13 of them prisoners, 8 women and 5 children, and took them back into the town; they also robbed them of their provisions.” The overstretched Americans seemed unable to protect the thousands of Indians on the move. One small distraction was all the slave takers needed to strike.

42

Bad as this was, three days after that the commanding officer at

Fort Canby received an urgent letter informing him that “a man who lives in Cebolleta, N.M. named Romaldo [Ramón] Baca has organized here & at other points, a party of 200 men, to go out with him, and steal the stock of the rich Navajos, now coming in to your Post.” Writing from Albuquerque, Major J. C. McFerron made one additional point: “Those belonging to his party are to leave for the general rendezvous in small parties so as not to excite attention to their movements.” Evidently Baca was well aware of the impending surrender of the rich Navajos and wished to make the most of the situation. He enjoyed great success, if we are to judge from other sources. For instance, one of his victims was the niece of a prominent Navajo chief named Herrero. She was eventually rescued and described in front of a military court how an armed party of “Mexicans from Cebolleta” attacked her camp at Casa Blanca, near Moqui, killing seven men and taking twelve prisoners, all women and children. Her two sisters were sold at Ranchos de Atrisco, close to Albuquerque, while some of the other prisoners were taken to southern New Mexico near Isleta, where they were finally disposed of. The geographic scope of these sales is noteworthy. Baca’s hometown of Cebolleta was already saturated with Navajos. A survey conducted in February 1864 yielded ninety-five Navajo peons, a remarkable number for such a minuscule settlement.

43

Ute war parties also were active. The historical record contains only sporadic references to their activities and is mostly lacking in detail. But we have indirect proof of their tremendous effectiveness. In July 1865, officials in Costilla County, in southwestern Colorado, conducted a detailed census of all Indians held in bondage. Sixty individuals were identified and listed by name, age, ethnicity, and date of capture. Fifty of them, or eighty-three percent, were Navajos, mostly children and women taken during the 1863–1864 campaign, as one would expect. In addition, the census provided rare information about the sellers. Of the sixty Indians listed, forty-eight had been sold by Mexican traffickers, ten by Utes, one by Apaches, and one by an unidentified individual. Clearly, Mexican dealers had the upper hand in Costilla County. However, an identical survey conducted in neighboring Conejos County told a very different story. Eighty-eight Indian peons were listed there, of whom

sixty-three, or seventy-one percent, were Navajos. In this case, fully forty-five had been sold by Utes, forty by Mexicans, two by Apaches, and one by an unspecified trafficker. Essentially, Ute and Mexican traffickers had split the slaving business in half in Costilla and Conejos Counties.

44

We can thus infer that both Mexican and Ute bands worked tirelessly that fateful spring of 1864. The situation was so dire that Kit Carson requested additional troops to pursue and capture “whatever bands of citizen marauders may come here for the purpose of thwarting the laudable actions of the government.” Similarly, Governor Henry Connelly issued a proclamation declaring all citizen forays into Navajo country “positively prohibited under the severest penalties” and warning against “further traffic in captive Indians.” It is doubtful, however, that Connelly’s proclamation made much of a difference.

45

The wholesale removal of the Navajo nation was tremendously disruptive not only for those who made it to Bosque Redondo but also for the scores of Navajos who were captured en route and sold off throughout New Mexico, Colorado, and northern Mexico. With good reason, the Navajos refer to this period as “the Fearing Time.” By the end of 1864, 8,354 Navajos were living at the Bosque Redondo reservation, according to reliable military censuses. That still left three to four thousand Navajos unaccounted for. Considering that a few hundred remained at large in remote areas and that hundreds more had perished during the campaign, it seems reasonable to assume that the number of enslaved Navajos was between one and three thousand. (Nearly seven hundred Navajos appear in baptismal records as dependents.) Wealthy New Mexicans each possessed four, five, or more Navajo slaves.

46

Americans had them too, from the governor down. The chief justice of New Mexico, Kirby Benedict, stated quite clearly that he had seen Indian slaves at the house of Governor Connelly, “but whether claimed by his wife, himself, or both, I know not.” The chief justice was also aware that superintendent of Indian affairs for New Mexico Michael Steck—the very federal official charged with enforcing U.S. policies toward Indians—possessed one female servant, “but I cannot state by what claim she is retained.” As far as the Indian agents working under Superintendent Steck, the chief justice assumed that “

all of them, except one,

have the presence and assistance of the kind of persons mentioned.” Their ranks included Kit Carson and Albert Pfeiffer, as we have seen. The situation was much the same among the American judges of New Mexico. Chief Justice Benedict recalled how in the spring of 1862, he had traveled with Associate Justice Sydney A. Hubbell with the intention of taking their families to the East, “and he informed me at Las Vegas that he sold one Indian woman to a resident of that place preparatory to crossing the Plains.”

47

The chief justice’s candid deposition makes clear that by the summer of 1865, nearly all propertied New Mexicans, whether Hispanic or Anglo, held Indian slaves, primarily women and children of the Navajo nation, who were “bought and sold by and between the inhabitants at a price as much as is a horse or an ox.” He estimated that the total number of Indian slaves in New Mexico ranged from fifteen hundred to three thousand, “and the most prevalent opinion seems to be that they considerably exceed two thousand.” In absolute terms, such figures may not sound like much, but the percentage was extremely high for the Navajo nation. For the present-day United States as a whole, it would be as if the population of California, Texas, or New York and New England combined were suddenly sold off into slavery.

48

The enslavement of Navajos in the 1860s was a direct result of the American conquest of the West. The federal government’s policies of removal gave Indian slavers extraordinary opportunities to ply their trade. The total number of Indians baptized in New Mexico in the 1860s was 846, almost seven times more than in the previous decade and far more than in any other decade going all the way back to the 1690s. Fully ninety-three percent of these baptized Indians were Navajos (see

appendix 7

). But at least there was some small consolation. Word of this sordid affair reached the ears of Washington politicians and abolitionist societies in the East. Something had to be done. After all, the United States was fighting a civil war ostensibly over slavery.