The Other Slavery (41 page)

Authors: Andrés Reséndez

When the survivors returned and news of their ordeal spread, the Pomos became infuriated. Still, Kelsey and Stone remained undaunted. In fact, they added insult to injury by planning to relocate all the Indians of the lake to the Sacramento River by Sutter’s fort. According to Augustine, a Pomo chief working as overseer for the two partners, the idea was to drive everyone away except the Indian vaqueros working directly in the cattle operation. To that effect, they commanded the Indians to make rope “to bind the young men and the refractory ones, so as to be able to make the move into the Sacramento Valley.” But having endured two years of unrelenting and vicious exploitation, having mourned the deaths of dozens of their brothers sent to the goldfields, and facing the prospects of massive relocation, “finally the Indians made up their minds to kill Stone and Kelsey, for, from day to day they got worse and worse in their treatment of them,” declared Chief Augustine a few years later, “and the Indians thought that they might as well die one way as another, so they decided to take the final and fatal step.” One morning in December 1849, the Indians charged the adobe house, killing Kelsey and Stone with arrows and striking their heads with rocks. The specific details of these killings vary from one version to another, but they all agree that the end of the two partners was grisly.

39

The scant literature on the early history of Clear Lake focuses on the cruelty of Andrew Kelsey and Charles Stone and the episodic massacres. But it tends to overlook a larger point: although the two American partners may have been unusually (even pathologically) cruel, they were able to enslave these Indians because such activities were common throughout the region and there was a thriving market for Indian slaves. Indeed, their deaths did not stop the trafficking of Clear Lake Indians.

The trade resumed in 1850 and became especially active from 1854 to 1857, when traffickers, revolvers in hand, regularly descended on small Indian bands, shot the men and sometimes the women, and caught the boys and girls between the ages of eight and fourteen. “Not many of the present generation of Californians know,” wrote Henry Clay Bailey, a Kentuckian who arrived in California at midcentury, “that in the early ’50s a regular slave trade was carried on in the mountains bordering the upper Sacramento valley from Clear Lake to Strong Creek.” The bounty of resources at the lake sustained a significant Indian population there that slavers continued to tap for years.

40

The prevalence of the other slavery in the mid-nineteenth century was reflected in legal statutes. Even as California hung in the balance between Mexico and the United States, on September 15, 1846, Captain John B. Montgomery, commander of the Northern Department of California, issued a proclamation warning people who “have been and still are holding to service Indians against their will” to desist and urging the general public not to regard Indians “in the light of slaves.” Yet the proclamation went on to state that all Indians living in the settled portions of California could not “wander about in an idle and dissolute manner,” but were required to obtain employment. Once their contracts had been fulfilled and their debts paid off, they were free to leave their employers. But they had to find another employer or master immediately, or they were liable to be arrested and drafted into public works.

41

The next step in the process of formalizing the peonage system was to give teeth to Montgomery’s proclamation, which is exactly what Henry W. Halleck, secretary of state of California, did by introducing a certificate and pass system in 1847. All employers were required to issue certificates of employment to their indigenous workers. If these workers had to travel for any reason, such as to visit friends or relatives or to trade, they also had to secure a pass from the local authorities. These certificates and passes allowed employers and local officials to monitor and control the movements of Indians. “Any Indian found beyond the limits of the town or rancho in which he may be employed without such certificate or pass,” Halleck ordered, “will be liable to arrest as a horse

thief, and if, on being brought before a civil Magistrate, he fail to give a satisfactory account of himself, he will be subjected to trial and punishment.” This system accomplished a number of goals. It allowed ranchers to hold Indians in place, as the certificates typically listed the “advanced wages” that had to be repaid before the certificate bearer would be free to go. This was the very cornerstone of the peonage system. The certificate and pass system also sought to minimize conflict among employers. Understandably, Indians often fled from ranches and mines and took up work with other employers. With these documents, prospective employers could determine at a glance if an Indian seeking employment had any outstanding debts. And finally, the pass system went beyond previous ordinances in distinguishing between Natives gainfully employed and all others—regardless of where they lived—who were automatically considered vagrants or horse thieves and therefore subject to the labor draft.

42

Captain Montgomery’s 1846 proclamation and Secretary Halleck’s 1847 pass system were important steps in the process of enshrining the peonage system into law. But by far the most sweeping piece of California labor legislation during the pre–Civil War era was the Act for the Government and Protection of Indians of 1850. As usual, this benign-sounding law was not what it purported to be. The committee that crafted it included the baronial Mariano Guadalupe Vallejo; David F. Douglas, a southerner from Tennessee with plenty of experience with the peculiar institution; and John Bidwell, the only moderate in the group. Bidwell was ill at the time, however, so it was up to the Mexican rancher and the former Tennessean to hammer out the final details. Their proposal quickly passed both houses on April 19, 1850, and was signed into law three days later.

43

It was an unwieldy piece of legislation containing twenty sections. Some of them were largely declarative; section 15, for example, prohibited the sale of alcohol to Indians. Otherwise the Indian Act of 1850 was like a piñata with something for everyone who wished to exploit the Natives of California. For instance, section 20 stipulated that any Indian who was able to work and support himself in some honest

calling but was found “loitering and strolling about, or frequenting public places where liquors are sold, begging, or leading an immoral or profligate course of life” could be arrested on the complaint of “any resident citizen” of the county and brought before any justice of the peace. If the accused Indian was deemed a vagrant, the justice of the peace was required “to hire out such vagrant within twenty-four hours to the best bidder . . . for any term not exceeding four months.” In short, any citizen could obtain Indian servants through convict leasing.

44

Another section established the “apprenticeship” of Indian minors. Any white person who wished to employ an Indian child could pre-sent himself before a justice of the peace accompanied by the “parents or friends” of the minor in question, and after showing that this was a voluntary transaction, the petitioner would get custody of the child and control “the earnings of such minor until he or she obtained the age of majority” (fifteen for girls and eighteen for boys).

45

The apprenticeship provision worked in tandem with yet another section of the Indian Act of 1850 that gave justices of the peace jurisdiction in all cases of complaints related to Indians, “without the ability of Indians to appeal at all.” And “in no case [could] a white man be convicted of any offense upon the testimony of an Indian, or Indians.” Understandably, these provisions gave considerable latitude to traffickers of Indian children. In northern California, this trade flourished, especially in the mid-1850s, and became so important that some newspapers began writing about the inhumanity of it. In 1857 the newspapers launched what one witness described as “an agitation against the California slave trade” and “a general crusade.” Very few traffickers were ever caught, however, and even those who were apprehended simply continued about their business after receiving just a slap on the wrist. Such was the protection afforded by the law.

46

These labor laws, and the debates surrounding them, harked back to the early colonial days. California declared that Indians were free, but they were not free to be idle, in much the same way that the Spanish crown in the middle of the sixteenth century abolished Indian slavery but still compelled Natives to work for their own good.

11

A New Era of Indian Bondage

T

HE AMERICAN OCCUPATION

of the West did not reduce the enslavement of Indians. In fact, the arrival of American settlers rekindled the traffic in humans. Conditions varied from place to place, of course. As the gold rush played out, California experienced the greatest demand for coerced Indian labor, but other territories had similar experiences. Easterners who had never participated in the market for Indians became immersed in it just by virtue of relocating to the West.

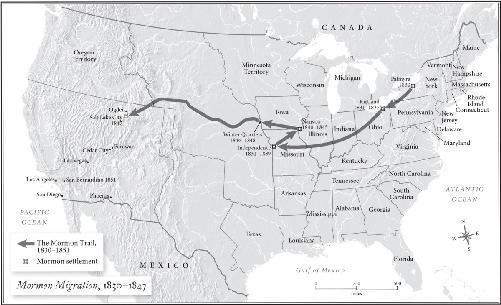

The Mormons began arriving in Utah in 1847 and attained a resident population of forty thousand by 1860 and eighty-six thousand by 1870. Scattered in settlements all around the Great Salt Lake and south of it, they eked out a living in the desert with considerable difficulty.

With respect to slavery, the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints had no set doctrine. However, Brigham Young, the undisputed Mormon leader, believed that slavery had always been a part of the human condition. “Eve partook of the forbidden fruit and this made a slave of her,” he affirmed in a major speech. “Adam hated very much to have her taken out of the Garden of Eden, and now our old daddy says I believe I will eat of the fruit and become a slave too. This was the first introduction of slavery upon this earth.” Young went on to explain how Cain murdered his brother Abel, and for this crime God put a special mark on all of Cain’s descendants: “You will see it on the countenance of every African you ever did see upon the face of the earth, or ever will see.” Some of the earliest Mormon pioneers possessed black slaves, and the Compromise of 1850—a set of congressional bills designed to defuse a confrontation between slave and free states—permitted Utah to decide whether to legalize chattel slavery by popular sovereignty.

1

Interestingly, Mormons had an explanation for the perceived characteristics of the Indian slaves they encountered in the West. According to the Book of Mormon, in ancient times different tribes of Israelites crossed to the New World. These tribes warred with one another until the only survivors were the descendants of Laman. For this reason, Mormons often referred to Indians as Lamanites. Like the Africans, the Lamanites were cursed by God, assumed a “dark and loathsome countenance,” and over the centuries grew fierce and warlike. Cut off from the teachings of God, the Lamanites became a degraded people. But since they were originally from the blood of Israel and therefore God’s chosen people, there was a glimmer of hope. One day the Lamanites could “blossom as the rose on the mountains,” as Wilford Woodruff, the fourth president of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, put it so arrestingly, “Their chiefs will be filled with the power of God and receive the Gospel, and they will go forth and build the New Jerusalem.” This would be a magnificent redemption in which the Mormons could play a part.

2

The path toward redemption began with enslavement. As the Mormons reached Utah in the summer of 1847, they began building a fort. That fall a band of Utes made camp in the vicinity. These Indians were just returning from a raiding campaign and had two girls whom they intended to exchange for firearms. The Mormons were initially reluctant to trade. They were not accustomed to acquiring Indians, rifles were scarce in Utah, and it was not wise to arm the surrounding Natives. As the Mormons could not agree on a deal among themselves, the Utes killed one of the prisoners and began torturing the other, a girl of about seven years of age. The traffickers made clear that they would kill her unless a rifle was forthcoming. Charles Decker, Brigham Young’s son-in-law, was the first to break down. He gave up his gun and took the girl. “She was the saddest looking piece of humanity I have ever seen,”

recalled one witness. “They had shingled her head with butcher knives and fire brands . . . She was gaunt with hunger and smeared from head to foot with blood and ashes.”

3

News of this transaction spread quickly. Over the next few years, Indians living in Utah made their way to the Mormon settlements, offering captives. These traffickers expected willing customers, but they were prepared to use the hard sell, displaying starving captives to arouse the pity of potential buyers. A Ute chief named Walkara became the most well-known supplier. “He has never been here with his band without having a quantity of Indian children as slaves,” recalled Brigham Young, “and I have seen his slaves so emaciated that they were not able to stand upon their feet. He is in the habit of tying them out from his camp at night, naked and destitute of food, unless it is so cold he apprehends they will freeze to death.” Other colonists had similar experiences: “[Walkara’s] children captives were like living skeletons,” wrote Solomon Nunes Carvalho, a Sephardic Jew who accompanied the famous frontiersman and explorer John C. Frémont on a visit to the Ute chief’s camp, “and were usually treated in this way, that is, literally starved to death by their captors.”

4