The Other Slavery (38 page)

Authors: Andrés Reséndez

The Canyon de Chelly, “the seat of the supreme power of the Navajo tribe of Indians,” as Indian agent James Calhoun described it, was both an extraordinarily fertile homeland and a formidable refuge. Timothy H. O’Sullivan took this photograph of “Camp Beauty” in 1873.

The travelers entered the canyon in silence. Streams of water laced the sides and bottom of this enormous oasis that supported extensive fields of corn, wheat, melons, squash, and beans, as well as peach orchards, which would have been especially green and lush in early September. Groves of pine, juniper, and cedar were visible all around, and water “in any desirable quantity” could be procured simply by digging a few feet into the stark reddish soil. Hundreds of Navajo warriors, taking up positions on the surrounding heights and “dashing with great speed from point to point, evidently in great perturbation,” closely monitored the progress of the American delegation.

4

Early the next morning, the head chief of the Navajo nation, Mariano Martínez, presented himself with some warriors and requested to

see the New Mexican governor. The two leaders had a long conversation and agreed to sign a treaty the very next day. In the past, whenever the Navajos had faced punitive expeditions sent out by the Spaniards, Mexicans, or Americans, they had been quick to negotiate. And in every case, the treaty-making ritual had involved giving up some captives. Chief Martínez returned the day after the initial conversation accompanied by four captives: Antonio José, a ten-year-old from Jemez; Teodosio, another boy taken from “a corral near the Rio Grande”; Marceito, a young man from Socorro who had been held in captivity for many years and was no longer able to speak Spanish; and José Ignacio, an adult originally from Santa Fe who had refashioned himself as a Navajo and had two wives and three children, even though he still belonged to an Indian named Wato. Exactly how Chief Martínez persuaded the owners to part with these four individuals is not known.

5

At that time, the Navajos held hundreds of slaves seized in raids on the Pueblos, Utes, Apaches, Hispanics, and Americans. These multiethnic captives rendered valuable services tending orchards and cornfields and looking after the large flocks of sheep accumulated by the people of the canyon. Indeed, a slaveholding class seems to have emerged among the Navajos. A dozen or so “rich” headmen each held up to forty or fifty slaves and peons, along with many other Navajo dependents. A key provision of the treaty between Martínez and the New Mexican governor required the Navajo nation to surrender “all American and Mexican captives . . . on or before the ninth day of October next,” exactly one month after the day of the signing. As for the four captives about to be released, although the two boys were excited to return to their families, the adults were not as enthusiastic. The novelty of a home in a New Mexican town “seemed to excite [Marceito] somewhat,” while José Ignacio much preferred to remain with his Navajo family, “notwithstanding his peonage.”

Agent Calhoun met these captives and followed their fates until they were returned, except for the one “so fortunately married,” who was allowed to stay with the Navajos. This was his first recorded experience with the other slavery. The Georgian had lived all his life surrounded by black slaves and was not particularly interested in Indians in general.

His letters are entirely lacking in references to the ancient ruins or theories of past civilizations that impressed so many other travelers. But his familiarity with chattel slavery in the South made him an ideal observer of Indian bondage in the West, apt to elaborate on its details and draw comparisons.

By the time Calhoun had spent six months as an Indian agent, he had formed a clear image of New Mexico as a land with a core population of Pueblo Indians, Mexican villagers, and Americans surrounded by what he called “the four wild tribes”—the Apaches, Navajos, Utes, and Comanches. “Those within the circle and those who form the circle look upon each other as natural enemies,” Calhoun explained to his superiors in Washington, “and they are eternally at war, robbing and enslaving each other.” Out of the four “wild tribes,” the Navajos alone possessed all the necessities of life, according to Calhoun. They cultivated the soil very successfully, owned enormous herds of goats and sheep, and wove some of the finest blankets in the region. They could live on their own without preying on others. The agent was convinced, however, that the other three groups survived “chiefly” by their depredations. Getting the Apaches, Utes, and Comanches to stop their raiding campaigns would require enormous outlays of money by the U.S. government and a strong military presence. Nothing less would accomplish a lasting peace.

6

In the meantime, a market for captives thrived in New Mexico. Calhoun described this market in some detail. The first thing he observed was that Indian captives in New Mexico were not referred to as “slaves” but as “peons.” Clearly, the shift to debt peonage was well under way there, and the system was highly coercive. According to Calhoun, peons could escape their servitude only by paying a certain amount to their owners. Indeed, the Indian agent likened peonage to chattel slavery: “

Peons,

you are aware, is but another name for

slaves

as that term is understood in our Southern States,” he explained in a letter to the commissioner of Indian affairs, adding that the main difference was that the peonage system was not confined to a particular “race of the human family,” but applied to “all colors and tongues.” Indians purchased other Indians, and Mexicans bought other Mexicans, and yet no one seemed to have the slightest objection to being purchasers of their own “kith

and kin.” Quite to the contrary, they believed that “the right to buy and sell captives is perfect and that no human power can disturb that right.”

7

After broaching the terminology and describing the enthusiasm with which New Mexicans engaged in this other form of enslavement, Calhoun provided some details about the market for captives and relationships with peons. Unlike Georgia or Louisiana, where slave auctions were held in public and centralized places, in New Mexico the traffic of humans was a great deal more fragmented, as owners bought captives from comancheros and acquired “the labor” of convicts at public auctions. They also haggled privately with their peons over debts and terms of service. Despite the nature of these scattered transactions, New Mexicans tacitly agreed on approximate price ranges for different types of captives, criminals, and peons. Their value depended on “age, sex, beauty, and usefulness,” reported Calhoun. “Good looking females, not having passed the ‘sear and yellow leaf,’ are valued from $50 to $150 each; males, as they may be useful, one-half less, never more.” This remarkable price premium for females harked all the way back to the sixteenth century.

8

Like many other Americans, Calhoun accepted the bondage system that existed in the West. He reported the practice to his superiors and learned many details about it, but he did nothing to prevent Hispanics and Anglo-Americans from holding men, women, and children in peonage. Only in cases covered by article 11 of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, which required the return of all Mexican captives, did the Indian agent make efforts to secure the release of those in bondage. Even in those cases, Calhoun purchased the captives from their owners, thus validating the system, even as he returned them to their families across the border.

9

American Ranchers

Calhoun merely tolerated the other slavery of the West, but other Americans went several steps beyond that by actively practicing it and enshrining it in law. In the 1840s, colonists were attracted to California

because of its broad valleys and booming ranching economy. There they found a baronial society that impressed them deeply. About one hundred Mexican families owned princely domains scattered from San Diego to San Francisco Bay. It is easy to imagine the rolling hills, the properties that in some cases extended all the way to the spectacular California coastline, and the large houses made of thick adobe walls. These houses were a curious combination of grandeur and lack of material comforts, however, as there were few possessions inside. These enormous ranches had originated in a well-meaning but ultimately disastrous order from Mexico City. In 1833 the Mexican government had mandated the dismantling of the Spanish missions that had long served as California’s social and economic backbone. Mission Indians were to receive plots of land, seeds, cattle, and tools. The predictable result, however, was a landgrab, as wealthy and well-connected individuals took the lion’s share of the land.

10

In northern California, the personification of the ranching baron was a rotund man with bushy sideburns named Mariano Guadalupe Vallejo, or Don Guadalupe for short. As military commander, Don Guadalupe personally welcomed foreigners. He spoke French well and English tolerably (according to one discerning witness) and was quite gregarious. Indeed, Don Guadalupe invited recent arrivals into his home and displayed a hospitality that became legendary. The Vallejos killed cows and turkeys to feed guests and offered tamales and enchiladas liberally. After these meals, guitars were tuned, and singing and dancing could be expected. Englishmen, Americans, Frenchmen, Swedes, Swiss, and Russians all passed through the Vallejos’

casa grande

in Sonoma.

11

One of the first things visitors noticed at the Vallejos’ home was the ubiquitous crews of servants. In a custom reminiscent of the antebellum South, each of Don Guadalupe’s children, boys and girls, had a dedicated Indian servant. Don Guadalupe’s wife, Doña Francisca Benicia Carrillo, had two servants catering to her personal needs. Besides these personal valets, the Vallejos kept a sizeable staff around the house: five or six women grinding corn and making tortillas, six or seven laboring in the kitchen, “and though not learned in the culinary art as taught by Italian and French books, they made very palatable and savory dishes,”

recalled Don Guadalupe’s younger brother, Salvador Vallejo. There were five or six women washing clothes and up to a dozen sewing and spinning. According to the younger Vallejo, it was not uncommon for wealthy Californians to keep retinues of twenty to sixty Indians.

12

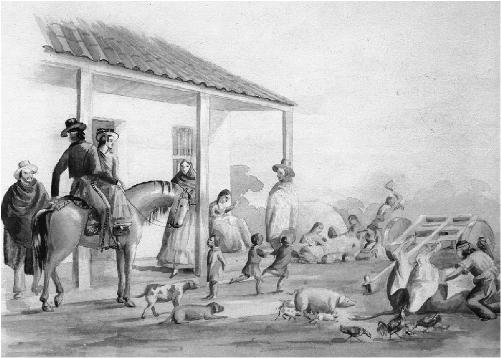

Ranch scene in Monterey, California, around 1849. A wealthy Mexican couple ride by a sturdy house as an Indian servant butchers a cow on the right, and Indian girls make bread in the background.

Foreign visitors who ventured out of Don Guadalupe’s home and onto his nearby Rancho Petaluma were able to gain a great deal more insight. At its peak in the early 1840s, this 66,000-acre ranch was tended by seven hundred workers. An entire encampment of Indians, “badly clothed” and “pretty nearly in a state of nature,” lived in and around the property and did all the work. As Salvador Vallejo recalled, “They tilled our soil, pastured our cattle, sheared our sheep, cut our lumber, built our houses, paddled our boats, made tiles for our houses, ground our grain, killed our cattle, dressed their hides for the market, and made our unburned bricks; while the women made excellent servants, took good care of our children and made every one of our meals.” The Vallejos

were quick to paint a picture of benevolent patriarchy. “Those people we considered as members of our families,” Salvador Vallejo remembered. “We loved them and they loved us. Our intercourse was always pleasant: the Indians knew that our superior education gave us a right to command and rule over them.”

13

But what seemed pleasant and natural to the Vallejos was decidedly less so to the Indians. Some workers at Rancho Petaluma were former mission Indians. As administrator of the mission of San Francisco de Solano, Don Guadalupe had ample opportunity not only to dispose of mission lands and resources (in fact, his Sonoma home, the military barracks, and the entire plaza lay on former mission lands) but also to bind ex-neophytes to his properties through indebtedness. Faced with dwindling resources and loss of land, former mission Indians had little choice but to put themselves under the protection of overlords like the Vallejos. Other Indian laborers had been captured in military campaigns north of Sonoma. As

comandante

(commander) of the northern California frontier, Don Guadalupe had a guard of about fifty men to keep order in the region and prevent Indians from stealing cattle. He also used his guardsmen to procure servants. He was not alone in doing so. Especially after the secularization of the missions in 1833, Mexican ranchers sent out armed expeditions to seize Indians practically every year—and as many as six times in 1837, four in 1838, and four in 1839.

14