The Other Slavery (17 page)

Authors: Andrés Reséndez

Their slave-taking enterprise was neither a residue of colonial wars nor a transitional phase until sufficient numbers of African slaves arrived in the New World. Rather it was a

system,

one with extraordinary staying power recalled fifty years after Carvajal’s inquisitorial tribulations by Alonso de León, another notable frontiersman and the first chronicler of the New Kingdom of León: “In those days, we did not consider anyone a man until he had journeyed to the Indian

rancherías,

whether friends or enemies, and seized some children from their mothers to sell; and there was no other way to sustain ourselves or open new trails without tremendous difficulties.”

42

4

The Pull of Silver

T

HE CALIFORNIA GOLD

rush transformed the western United States. Within one decade of James W. Marshall’s discovery of a few flecks of gold in a ditch in 1848, some three hundred thousand migrants had moved to California. These Chinese, Italian, German, Chilean, and other newcomers turned the remote and picturesque Mexican outpost of San Francisco into a bustling port. They also fanned out into the Sierra Nevada to build cabins, divert rivers, and pan for the yellow metal. This is a familiar story of long journeys, ethnic conflict, broken dreams, and explosive growth.

1

Yet the California gold rush was neither the largest metal-induced rush of North America nor the most transformative. By any measure, that title belongs to the earlier Mexican silver boom. In terms of duration, for instance, the California gold rush was like a hurricane. Gold production skyrocketed in 1849 but peaked as early as 1852, only four years after the start of the rush, and declined markedly thereafter. For all practical purposes, the rush was over by 1865, lasting less than twenty years. The use of pressurized water to wash down entire hillsides—a process known as hydraulic mining—kept gold production from declining even faster than it did. By contrast, Mexico’s silver boom started in the 1520s and grew through the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, reaching a plateau at the end of this period. Remarkably, it gained

a second wind in the late seventeenth century and kept increasing during the eighteenth century, not attaining its high-water mark until the first decade of the nineteenth century—almost three centuries after the boom had begun. By then silver was the principal way in which empires and nations around the world stored their wealth, and the Spanish peso had emerged as the first global currency, used throughout the Americas, Europe, and Asia, where it was often countersigned (authenticated by the treasury or other monetary authorities) and employed in everyday transactions. It remained legal tender in the United States until 1856.

2

The very royal-looking Spanish peso was made of almost pure silver. Minted in the Iberian Peninsula as well as in Mexico City, Lima, Potosí, and smaller towns in the New World, the peso was in demand throughout the world. The largest consumer of silver during the colonial era was China.

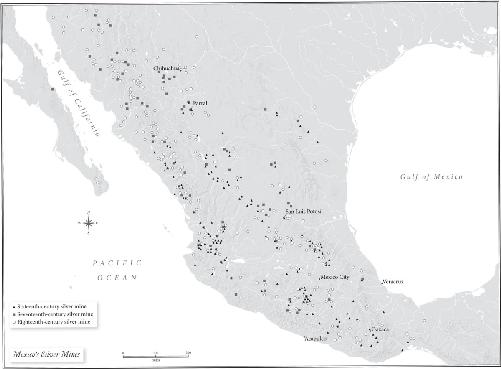

Not only did the Mexican silver boom last longer than the California gold rush, but it was more extensive. The gold rush was confined largely to the northeastern quadrant of the state, with a few additional mines sprinkled along its border with Oregon and in southern California. Prior to the gold rush, there had been small strikes in the southern Appalachians (North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, and Georgia), and after the California discoveries, new goldfields emerged in some of the Rocky Mountain territories. Mexico’s centuries-long silver boom surpassed these gold strikes in both geographic scope and sheer density. Historians usually refer to the mines of

northern

Mexico, but in truth the silver boom started in southern and central Mexico. Present-day tourists driving from Mexico City to Acapulco still stop at Taxco (1534), a silver town that Hernán Cortés himself developed. Taxco was part of a cluster of mines in southern Mexico that included Sultepec (1530), Amatepec (1531), Zacualpan (circa 1540), Zumpango (1531), and others. Only gradually did prospectors venture north into the lands of the Chichimecs, along the Pacific coast and up into the escarpments of the Sierra Madre Occidental. They had to bring in Indians from central Mexico as workers and overcome other tremendous logistical problems, but they succeeded in establishing a string of mines throughout western Mexico. After this initial push, prospectors crossed the Sierra Madre, proceeding on to the central plateau, where they founded some of the richest mines in the world, including Zacatecas (1546) and Guanajuato (1548). But even these mines were not sufficient. Spaniards next explored the present-day states of Durango and Chihuahua, as well as parts of northeastern Mexico. Altogether, they founded more than 400 mines (143 in the sixteenth century, 65 in the seventeenth century, and 225 in the eighteenth century) scattered throughout much of Mexico, from the semitropical regions of the south to the deserts of Chihuahua, and from the Pacific to the Atlantic coast.

3

Given its longer duration and more extensive geography, it is no wonder that Mexico’s silver boom produced roughly twelve times as much metal as the nineteenth-century gold rushes in the United States—44.2 million kilograms (48,722 tons) of silver compared with 3.7 million kilograms (4,078 tons) of gold (see

appendix 4

). This massive production is even more impressive considering the work and danger involved. The gold of California lay in placers, or surface deposits of sand and gravel, which had resulted from mountains eroding and yielding nuggets or flecks of gold, which collected at lower elevations along hillsides and in streams. Mining these bits of precious metal required a great deal of superficial digging, carrying, and washing. As we saw earlier in the Caribbean, that could be very hard work, but it was not nearly as daunting or dangerous as mining silver. Instead of lying in open-air deposits, the silver had to be extracted from deep underground. The main shaft

in the mines of San Luis Potosí was 250 yards long, and that in the Valenciana mine in Guanajuato plunged 635 yards down. When this shaft was completed around 1810, it was considered the deepest man-made shaft in the world. Digging to such depths required an untold amount of work, and yet this was only the beginning of a long, involved process that required bringing the ore to the surface (frequently on the backs of humans), crushing the rocks into a fine powder, and mixing that powder with toxic substances such as lead and mercury.

4

If the silver boom had occurred in the nineteenth century, Mexico would have become a worldwide magnet, like California. In an era of newspapers, steamboats, and widespread transoceanic travel, there is little doubt that the great Mexican silver mines would have lured immigrants from all quarters of the globe. But because the boom predated these communication and transportation conveniences and unfolded at a time when the Spanish monarchy prohibited all foreigners from going to the silver districts, Mexico had to make do with its own human resources. Whereas California attracted three hundred thousand people, colonial Mexico had to satisfy a hugely greater labor demand with no access to volunteers from the rest of the world.

Parral

There is hardly a better place than Parral to explore the pull of silver. Today Parral is a scraggly town in southern Chihuahua, trying to cope with the closure of its mine after more than three and a half centuries of uninterrupted production and attempting to weather a drug-related wave of violence that has engulfed much of the state in recent years. Amazingly, it is succeeding by reinventing itself as a tourist destination. Visitors can witness a reenactment of the final earthly moments of the legendary revolutionary leader Pancho Villa, whose car was riddled with bullets at a Parral intersection. Tourists are also encouraged to spend time at the Palacio de Alvarado, a sumptuous late-nineteenth-century house that belonged to a mining baron. But the main attraction is the mine itself. Accompanied by a guide, one can descend into the bowels of the

hill overlooking Parral and then wander through an elaborate gallery of tunnels that were excavated beginning in the seventeenth century.

In colonial times, Parral was neither the largest nor the most productive silver mine in Mexico. It was certainly a major operation compared with dozens of flash-in-the-pan silver strikes, but it produced less silver than Zacatecas, Guanajuato, Pachuca, and possibly some other mines. And yet Parral had a profound influence on northern Mexico’s environment, economy, and human populations. Like Española’s gold mines—which may not have employed more than five thousand workers but were still responsible for a vortex of enslavement and death across the Caribbean basin—Parral became a hub of exploitation, its spokes extending far and wide throughout the region and even around the world.

5

It all began in the summer of 1631, when a peripatetic ensign named Juan Rangel de Biesma conducted diggings in a hill that he called “La Negrita,” probably in reference to the gray-black color of the rocks there. Rangel de Biesma had only recently moved into the region and was a complete novice in the mining business. Less than a year earlier, he had relocated from his native Culiacán, on the Pacific coast, with his sister, who had married an encomendero from the Parral area. The thirty-year-old took up residence with the young couple at an estate that happened to be barely two miles away from the hill. Perhaps merely to give him something to do, Rangel de Biesma was put in charge of a team of Indian servants whose job was prospecting for silver. For decades Spaniards had been searching the area, but wars with the Indians, the dense scrub oak, the lack of servants, and simple bad luck had conspired to prevent them from discovering the enormous treasure buried in that hill.

6

Rangel de Biesma and his team cleared an area close to the top and found that it was completely studded with black rocks. As far as anyone could tell, the vein was enormous, and the silver concentration was remarkable. Typically, miners were happy when they found ore containing one or two marcos per quintal (1 marco equals 230 grams, or a little over 8 ounces, and 1 quintal in colonial Mexico equaled 46 kilograms, or about 100 pounds). The samples from La Negrita reached

seven

marcos

per quintal. This was the discovery of a lifetime. Not since the strike of Zacatecas more than eighty years earlier had anyone stumbled on such a massive silver deposit.

7

No single individual, not even one in partnership with a powerful encomendero, could work the site by himself. So Rangel de Biesma invited family, friends, and neighbors, who claimed mining rights in adjacent areas. Word spread quickly beyond this small circle, and miners from other regions began pouring into the hill, bringing with them teams of black slaves and Indian servants. La Negrita soon came to resemble a giant anthill, with workers crawling around it, clearing scrub oak, digging tunnels, and carrying ore. By the start of 1632, just six months after the initial discovery, four hundred Europeans and as many as eight hundred “people of service” had settled by the hill. Those were heady years, when the riches of La Negrita seemed inexhaustible. As one enthusiastic miner put it, “The entire hill is made up of silver.”

8

Over the next decade, Parral’s population continued to grow by leaps and bounds, surpassing 5,000 in 1635 and 8,500 by 1640. An entire city mushroomed at the base of the hill. Urban centers in Spanish America were usually arranged in a characteristic checkerboard grid, departing from a central plaza with a church on one side and a government building on the other. Yet Parral sprouted helter-skelter. The town’s houses—initially no more than leather tents resembling Indian tepees—were crowded as close to the hill as possible. With the passage of time, these temporary quarters turned into more permanent

jacales,

adobe structures surrounded by corrals and vegetable plots. Parral’s eastern end was the only section that resembled a real city. A vacant square lot grandly known as

la plaza del real

was surrounded by the sturdiest houses, a church, and the principal stores. Francisco de Lima, one of Parral’s foremost merchants, owned an entire block of houses opposite the plaza, where he sold overpriced clothes, basic foodstuffs, and, occasionally, Indian slaves brought from New Mexico. The captives were auctioned off right in the plaza. In comparison to present-day cities, Parral’s 8,500 inhabitants may not sound like much, but in the seventeenth century it was the largest town north of the Tropic of Cancer in the Americas

.

And nowhere else in what is now northern Mexico, the

United States, or Canada were there more Indians or a larger concentration of African slaves living in a single place.

9