The Other Slavery (14 page)

Authors: Andrés Reséndez

Carvajal may have lived out his whole life on the African islands had it not been for the arrival of a fantastic business opportunity. In the early 1560s, the Portuguese and Spanish monarchies began negotiating a major slave contract. Cape Verde was to supply eight thousand slaves over a period of four years at a price of about 100 ducats apiece. The king of Portugal sent a representative to Seville to settle the last remaining details. It is probable that Duarte de León needed representation for the negotiation in Seville, and what better choice for such a task than his own nephew, who had grown up in Spain, could conduct himself as a Spanish gentleman, and had ample experience in the slaving business. In 1564 Carvajal traveled first to Lisbon, where he stayed briefly, and then to Seville, where he remained for two years as negotiations first stalled and finally broke down. The two Iberian monarchies could not agree on a price. It must have been a major setback for Duarte de León’s

syndicate, but by then the former agent of Cape Verde was already dreaming of new ventures and his own network in the New World.

8

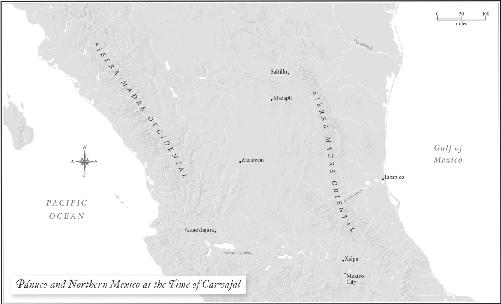

Pánuco Slaves

Carvajal traveled to Mexico in the summer of 1567 as a man of means and enterprise. He took his own ship, carried a full load of wine, and transported several passengers, including high-ranking officials. He settled in the province of Pánuco, a marshy area on the Gulf of Mexico to the south of Texas. A province that was well populated and easily accessible by land and sea, Pánuco had been an active slaving ground for dec-ades. Early Spanish colonists were delighted to learn that the Natives of the area did not have “universal lords” like the Aztecs and Tarascans, but “individual chiefs,” and that they waged war “as if they were Italian city-states” and took captives from one another.

9

Faced with these propitious circumstances, settlers began acquiring Natives as early as the 1520s and selling them to the slave traffickers of the Caribbean. Pánuco initially funneled many slaves to the goldfields of Cuba and Española. This trade flourished especially under the energetic governorship of Nuño de Guzmán, who issued licenses to all Spanish residents “so each of them could take twenty or thirty slaves.” Guzmán also fitted out his own ships, which he loaded with Pánuco Indians to trade for cattle from the islands. The first bishop of Mexico, Friar Juan de Zumárraga, estimated that by 1529 “around nine or ten thousand branded Indians from Pánuco had been traded for animals.” This barter was so brisk that Pánuco experienced what some scholars refer to as an “ungulate explosion.” Northeastern Mexico amassed the largest cattle herds in sixteenth-century North America and paved the way for the ranching empire that would flourish in Texas in later centuries.

10

By the time Carvajal arrived in Pánuco in 1567, the local traffickers were no longer selling slaves in the Caribbean. The development of silver mines in central and northern Mexico in the 1540s and 1550s had completely transformed the slave trade. Pánuco merchants had reoriented their business away from Cuba and Española and toward the interior of Mexico, organizing caravans and pioneering new land routes to principal mining centers there. When Carvajal arrived, he simply adapted to the system of enslavement already in place.

The most insightful testimonies about the workings of the Pánuco slave trade come not from indigenous victims but from a band of English pirates who washed up on the Gulf coast in October 1568. The Englishmen hacked at the brambles and bushes that tore their clothes and assaulted their bodies. They made their way through thickets of grass that grew taller than a man “so we could scarce see one another,” recalled one of the men, Miles Phillips. As the days passed and the pangs of hunger increased, their morale plummeted. The pirates disagreed about how best to save themselves and went their separate ways. What had once been a contingent of 114 men splintered into several smaller groups, reducing their ability to resist Indian attacks or capture by Spanish authorities. Phillips cast his lot with a group that chose to travel south along the coast hoping to find a town that would take pity on them.

11

These raggedy Englishmen were themselves slavers. A year earlier, they had arrived in Plymouth, England, to sign up for what must have seemed an exceptionally promising expedition. Queen Elizabeth, along with thirty merchants from London, had invested heavily in the venture. John Hawkins, a legendary privateer on his third slaving voyage, took command of the fleet, accompanied by “M. Francis Drake, afterward knight.” The ships headed first to Cape Verde and the coast of Guinea, where they procured “very near the number of 500 Negroes,” and then crossed the Atlantic and lurked in the Caribbean and the Gulf of Mexico in search of buyers. Problems arose when the pirates became overconfident and entered Mexico’s principal port of Veracruz, where they were hemmed in by a Spanish fleet. The ensuing battle resulted in the loss of all but two of the English ships. Hawkins and Drake were lucky to escape on these vessels, scampering north along the coast but carrying too many passengers and too few provisions. Hawkins decided to put ashore more than one hundred men with the promise that “the next year he would either come himself, or else send to fetch them home.”

12

For eight days, Miles Phillips’s abandoned group managed well enough. According to him, the men were “feeble, faint and weak,” but

they resolutely walked along the coast, braving “a kind of fly, which the Spaniards called mosquitoes . . . [that] would suck one’s blood marvelously.” The pirates also ran into a group of “Chichimecas,” as Phillips called them, using the generic term applied to the hunter-gatherer societies of northern Mexico. In his opinion, they were “very ugly and terrible to behold” on account of their very long hair, “even down to their knees,” and because “they also colour their faces green, yellow and blue.” At first the Indians attacked the Englishmen—mistaking them for Spaniards—“shooting off their arrows as thick as hail.” But once they became aware of the strangers’ desperate circumstances, they showed remarkable restraint, making the castaways sit down while they went through the pirates’ belongings. The nomadic Indians took some colorful articles of clothing (“those that were appareled in black they did not meddle withal”) and then left without harming them.

13

The pirates’ good fortune ran out when they approached the Pánuco River. Not having tasted water in six days, they rushed to the stream and drank in great gulps. They were resting still when they saw Spanish horsemen riding up and down the river on the opposite bank. Phillips saw the Spaniards dismount, step into canoes, and begin crossing the river, their horses tied by the reins and swimming behind. “And being come over to that side of the river where we were,” he wrote, “they saddled their horses and came very fiercely running at us.” The pirates had no choice but to submit peacefully. With only two or three rusty swords in their possession, it would have been futile to resist; flight was entirely out of the question. They crossed the river in the Spanish canoes in groups of four and made their way to the nearby town of Tampico.

14

The Englishmen’s lives were now in the hands of none other than Luis de Carvajal. The former Cape Verde agent had been in the port of Tampico for only a few months. He had bought a cattle ranch near town, and being a man of wealth, he also had purchased the appointment of

alcalde ordinario,

or lower magistrate. At the time, the town had a resident population of about 40 Europeans and 150 Indians. It was Carvajal who had received news of the English pirates roaming on the Pánuco coast and had organized the troop of Spanish horsemen who had spotted the castaways on the river.

When the prisoners filed into town, Carvajal interrogated them, “showing himself very severe,” and threatened to hang them on the spot. After demanding the scant money and valuables they carried, he had the Englishmen locked up in the public jail—“a little house much like a hogsty”—in a space so small that the men nearly smothered one another. And when they asked for a surgeon (doctor) to treat their wounds, they were told, according to Phillips, that “we should have none other surgeon than the hangman, which should sufficiently heal us of all our griefs.”

15

The pirates remained in this condition for three days. On the fourth day, Phillips and the others sensed that many Spaniards and Indians had massed outside the building. The captives feared the worst. When the doors opened, they filed out of the cell, crying to God for mercy. Waiting outside were several guards and a man with newly made leather halters. Uncertainty and the ever present fear of immediate and painful death were key to the psychology of enslavement. “With those halters,” Phillips wrote, “they bound our arms behind us, and so coupling two and two together, they commanded us to march on through the town, and so along the country from place to place towards the city of Mexico, which is distant the space of ninety leagues [270 miles].” From the hot and humid coastal plains of Pánuco, the captors marched the English pirates in the very fashion and along the very routes that innumerable Indian slaves had followed through towns and ranches, paraded and showcased for the benefit of potential buyers. Had the prisoners been “Chichimecas,” they would have already been sold along the way. But since they were Englishmen, they were destined for Mexico City.

16

Driving the caravan were two Spaniards and “a great number of Indians warding on either side with bows and arrows, lest we should escape.” This method for transporting captives by tethering them in lines was common throughout northern Mexico and bore more than a passing resemblance to African “coffles,” caravans of shackled slaves. One of the Spanish guards was an old man whose task was to procure provisions. He went ahead of the moving body to warn the authorities in the next town and make preparations. Always short on resources, he had to rely on charity to feed and clothe the prisoners and attend to their

medical needs. The other Spaniard was young and “a very cruel caitiff,” according to Phillips’s account. He was responsible for preventing escape and for driving the column on schedule. He carried a javelin, “and when our men with very feebleness and faintness were not able to go so fast as he required them, he would take his javelin in both his hands, and strike them with the same between the neck and the shoulders so violently, that he would strike them down.” The driver would then say aloud,

“Marchad, marchad Ingleses perros, Luteranos, enemigos de Dios

or

[M]arch, march on you English dogs, Lutherans, enemies to God.”

17

When the column entered Mexico City, men and women came out to see them. Many were sizing up the English captives, already thinking how much to offer for them. For six months, the prisoners remained in a hospital on the outskirts of the city. “We were courteously used,” Phillips observed philosophically, adding that they received visits from gentlemen and gentlewomen from the city, who gave them “suckets [sweets] and marmalades, and that very liberally.”

18

At last the viceroy of Mexico ordered that the men be transferred to certain “houses of correction” in Texcoco, also on the outskirts of Mexico City, “which is like to Bridewell here in London,” the young Englishman wrote, referring to the notorious English workhouse for paupers and criminals. Indians were routinely marched to these houses of correction and “sold for slaves, some for ten years, and some for twelve.” Phillips’s heart sank to the ground: “It was no small grief unto us when we understood that we should be carried thither and be used as slaves, we had rather be put to death.”

19

Spanish gentlemen and ladies gathered at a garden in Texcoco belonging to the viceroy in order to choose their English slaves. “Happy was he that could get soonest one of us,” Phillips observed. Each new owner simply took his or her slave home, clothed him, and put him to work in whatever was needed, “which was for the most part to attend upon them at the table, and to be as their chamberlains, and to wait upon them when they went abroad.” Like the liveried Africans who waited on their wealthy masters around Mexico City, these Englishmen represented conspicuous consumption, meant to be displayed to houseguests and on outings. Ordinary Indian slaves would not have fared so well.

20

Some of the English prisoners were sent to work in the silver mines, but there too they received favorable treatment, as they became “overseers of the negroes and Indians that laboured there.” Some of them remained in the mines for three or four years and, in a strange twist of fate, became rich.

21