The Other Slavery (15 page)

Authors: Andrés Reséndez

The experiences of Miles Phillips and the others differed in important respects from those of Indian slaves, but they were still subjected to the slavers’ methods. They traveled from Pánuco in a coffle, were sold in the slave markets of Texcoco, worked in the mines, and witnessed the living conditions of Indian men and women in bondage.

The Chichimec Wars

Carvajal’s involvement with the English pirates was momentous, but his greatest challenge by far had less to do with raggedy Europeans than with Indians. Carvajal’s arrival in Pánuco in 1567 coincided with a major escalation of the war against the nomads of northern Mexico. The Spanish push into the silver-rich lands of Zacatecas, Guanajuato, Durango, Mazapil, and others had triggered early skirmishes that grew into a no-holds-barred struggle known as the Chichimec Wars. At the time of Carvajal’s arrival, the

tierra de guerra,

or war zone, encompassed an enormous arc that stretched from the Pacific to the Atlantic coast. Although Mexico City and its immediate surroundings remained eerily quiescent, Spanish colonists and Indian allies who ventured into the north found constant danger. They lived in a patchwork of newly founded silver mines, cattle ranches, supporting settlements, and a few roads. The rest was Indian ground, and the violence was ever present. Carvajal’s chosen town, Tampico, lay right on the edge of the war zone. To the north began the lands of the Chichimecs. All one had to do was cross the Pánuco River to run into roaming Indians like the ones the English pirates had encountered in the fall of 1568. The Chichimec Wars were all too real in Tampico. An English visitor recounted that during his brief stay there in 1572, Indian raiders killed fourteen Spaniards who had ventured just to the outskirts to gather salt.

22

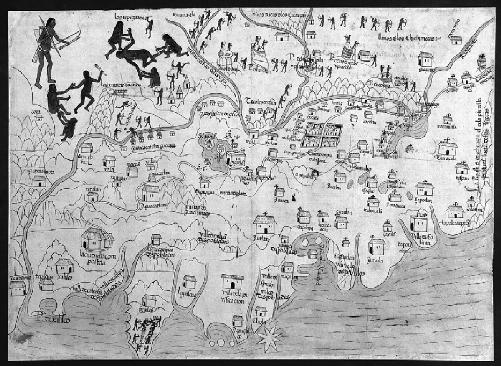

This 1550 map of what is now western Mexico reveals the violence and mayhem of the Chichimec Wars. Spanish towns and settlements are surrounded by Indians who are carrying bows and arrows, attacking colonists, and taking captives.

When we try to imagine this conflict, it is tempting to fall back on the imagery of America’s nineteenth-century frontier, where white settlers confronted equestrian Indian societies such as the Comanches and Utes that possessed firearms. Yet sixteenth-century Spaniards faced a very different challenge. The Chichimecs overwhelmingly moved on foot, and they fought strictly with bows and arrows. Before engaging in combat, they took off all their clothes and taunted the Spaniards, who were attired in heavy coats and chain mail. They were each armed with only a bow and four or five arrows, which they could deliver with lethal speed and precision. Many a Spanish colonist was pierced while desperately fiddling with his flintlock harquebus, priming horn, and firing hammer. Capture was frightful. “Regardless of whether it is male or female,” wrote an Augustinian friar who had lived among Guamares and Guachichiles and was otherwise quite sympathetic to the nomads, “the first thing they do is remove the top of the head, taking off all the skin and leaving the

skull clean just like one takes a friar’s tonsure.” Although scalping was usually fatal, the friar met a Spaniard who had been scalped years before and, in a different incident, a woman “who survived many days.” The Chichimecs were also known for impaling their victims, cutting off their arms and legs while they were still alive, and removing their tendons, which were used for tying arrowheads to shafts. Reports of robberies, killings, abductions—all manner of atrocities—poured into Mexico City as the entire Chichimec arc burst into flames.

23

The man held most responsible for doing something about the raging conflict was Viceroy Martín Enríquez de Almanza. Like Carvajal, Enríquez was a newcomer to the New World. In fact, he had traveled on the very fleet that had interrupted John Hawkins’s brazen trading mission in Veracruz in 1568, and he had participated in the fierce battle that had resulted in the sinking of all but two of the English ships. Enríquez’s order to attack the pirates had been risky, but it had paid off in the end. Enríquez had been pleased to learn a few days later that some of the Englishmen who had escaped from Veracruz had been apprehended by the energetic alcalde of Tampico. Thus an early bond was formed between Enríquez and Carvajal, both of whom were firm believers in decisive action.

24

Once in Mexico City, Viceroy Enríquez turned his attention to the war in the north. He convened a high-level council in 1569 in which the three main religious orders and other clergymen and lawyers would decide whether the war against the Chichimecs might be considered “just.” This was hardly an arcane legal exercise, but rather an official ruling that would determine whether Indians taken in the war could be legally enslaved. Most of the councilors sided with the viceroy in calling it a

guerra a fuego y a sangre,

or war by fire and blood, the designation that would permit the Spaniards to kill and enslave their Indian enemies. Only the Dominican friars went against the general opinion by arguing with undeniable logic that the Spaniards, not the Indians, were the true aggressors, and therefore that the war could not be considered “just” nor could the Chichimecs be enslaved.

25

Strictly speaking, Viceroy Enríquez could not grant a free hand to the Spaniards on the frontier, as such a policy would be in violation of

the New Laws of 1542. The Spanish king was the only one who could grant a general exception to the accepted regulations prohibiting the enslavement of Indians. So the practical Enríquez steered a middle course by calling it a war by fire and blood, but with limitations and euphemisms: Chichimec women and children could not be taken, captured adult males had to be tried and found guilty of a crime before “their service” could be sold, and they could not be enslaved in perpetuity, but only “held in deposit” for a specified number of years ranging from six to twenty. From a narrow legal perspective, these Indians would not be slaves, but rather convicts serving out their sentences. In an atmosphere of patent alarm over the nomads’ assertiveness, however, the viceroy’s middle course drew sharp criticism. The archbishop of Mexico, Pedro Moya de Contreras, was one of the viceroy’s most notable critics. He believed that assigning Indians to the soldiers who defeated them was a necessary reward for frontier service; that the wars in the north would be endless if Indian women and children could not be enslaved; and that no Spanish colonist would go to war if he had to go through the trouble of gathering information to determine the guilt of every Indian he captured. The archbishop’s views reflected a common opinion among colonists and ranchers.

26

The legal debate would rage for years, but for the time being the viceroy had enough support to wage his war. Throughout the

zona de guerra

(war zone), he named captains to punish robberies and murders and to keep the Chichimecs at bay. In Pánuco he bestowed this title on Carvajal. The former agent of Cape Verde was now the viceroy’s right-hand man in northeastern Mexico. Viceroy Enríquez’s orders to Carvajal spelled out in astonishing detail the parameters of his slaving activities. Captain Carvajal was to punish the rebellious Indians by executing the ringleaders and “doing justice in the manner of war.” As for other Indians found guilty of crimes, “their service should be sold for ten years,” with the exception “that no Indian under the age of twelve can be sold in service.” Carvajal soon demonstrated an uncommon talent for these endeavors. When he and his men caught up with offending Chichimecs, they carried out their orders to the letter, surrounding the Indians,

killing the leader, and taking about thirty captives, “whom he [Carvajal] punished in accordance with his commission.”

27

By 1576 more than six thousand Chichimec Indians had been reduced to slavery and were living in central Mexico, according to the conservative estimate of a crown official. Carvajal was now a full partner in the system of enslavement. It was a vast system that began with the Spanish king—even if only because he tolerated or overlooked the practice—passed through the viceroy and his advisers in Mexico City, and extended to the governors, captains, soldiers, and Indian allies who carried out the raids. It was not too different from the system Carvajal had known in Cape Verde. There too it had begun at the top, with the Portuguese granting trading privileges for portions of western Africa, which royal contractors and agents had proceeded to exploit. The main difference was that whereas in Africa the actual catching of slaves had been done by other Africans, in northern Mexico Spanish or mestizo captains did much of the capturing. Even that would change, however, as the slave trade in the New World evolved and passed largely into Indian hands.

28

Like any other slaving system, the one in northern Mexico boiled down to pesos. The expeditions into Chichimec lands were expensive undertakings that required up-front outlays of cash. Each soldier needed to pay for horses, weapons, protective gear, and provisions. Experienced Indian fighters estimated that a soldier could not equip himself adequately for less than 1,000 pesos. Yet the crown generally paid a yearly salary of only 350 pesos (which was increased to 450 pesos after 1581). So the first thing a captain had to do in order to attract soldiers and volunteers was to assure them that the campaign would yield Indian captives. Without being offered a chance to capture Natives, few would risk life or horse. Time and again, Carvajal faced this fundamental economic reality. On one occasion in the early 1580s when he was gathering men to put down an Indian rebellion in the Sierra Gorda, his volunteers became discouraged because they anticipated that the rebels would negotiate a truce at their approach. The Chichimecs were crafty, and this was a favored tactic. In that case, the men would be left with no captives,

and their provisions and other expenditures would be wasted. Would Carvajal pay the soldiers out of his own pocket? To overcome their reluctance, Carvajal reportedly placed his hands on a crucifix and told the men that “he swore by the Gospels that even if the rebellious Indians came in peace he would imprison them in such a way that for every ten Indians that came [in peace], five would remain in the land and the other five he would distribute to the soldiers.”

29

In short, punitive expeditions into the Chichimec frontier were economic enterprises. Investors offered loans or equipment to the volunteers, who would repay them through the sale of captives at the end of the campaign. Detailed records of such financial arrangements are rare, but the unhappy end of soldier Gaspar de Ribera gives us a glimpse. Ribera served under Captain Francisco Cano near the mines of Mazapil in the vicinity of Pánuco. In October 1569, Ribera and his companions cornered a group of Chichimecs in a cave not far from the silver mines. But as Ribera stepped up to the entrance, an arrow flew straight into his left eye, and another lodged in his head, killing him almost instantly. When Captain Cano settled Ribera’s estate, he discovered that Ribera was in partnership with a widow from Mazapil named Constanza de Andrada. This redoubtable frontier woman had advanced horses and arms to the soldier in exchange for half of his share of the spoils. During the campaign, Ribera had earned two Guachichil Indians, a girl of twelve and a woman of twenty-five. The captain felt compelled to honor the terms of Ribera’s agreement with Andrada. So he sold the Indians to the highest bidder—70 pesos for the two—and transferred half of the proceeds to the widow. The arrangement between Ribera and Andrada makes painfully clear how the expeditions functioned as investment vehicles and why soldiers were so keen on taking captives.

30

Carvajal established himself as an able frontier captain, rounding up English pirates, subduing rebellious Indians, and blazing new trails. And as he made himself the master of Pánuco, his ambition grew. With the full backing of the viceroy, Captain Carvajal traveled to Spain in the summer of 1578 to ask for a royal contract. It took him about ten months of lobbying at the court of Philip II, but the results were spectacular. Carvajal was named governor and captain general of the New

Kingdom of León, the largest kingdom north of New Spain (Mexico).

31

It comprised a gigantic quadrangle measuring two hundred leagues (more than six hundred miles) north to south and another two hundred leagues east to west, encompassing all of the modern states of Tamaulipas (Pánuco), Nuevo León, and Coahuila; almost all of Zacatecas and Durango; and portions of San Luis Potosí, Nayarit, Sinaloa, Chihuahua, Texas, and New Mexico. Captain Carvajal was already an integral part of the slaving system of northern Mexico. With this appointment, he would have tremendous autonomy to profit from the traffic of Indians, and even the opportunity to create his own slaving system.