The Other Slavery (11 page)

Authors: Andrés Reséndez

Notwithstanding the legal experiences of Beatriz and Catalina, the evidence indicates that the majority of Indian litigants won their cases. The archives in Seville contain several documents that attest to these legal victories: “royal order addressed to the justices of these kingdoms and of the Indies granting freedom to the Indian Magdalena who had been a slave of Esteban Vicente from the town of Medina del Campo”; “order against Juan de Jaén, priest of Fregenal, about setting the Indian that he had as a slave free”; and “order to Catalina de Olvera, resident of Santa Olalla, about granting freedom to the Indian Inés who she had as a slave,” among many others. Contextual information contained in some of these judicial proceedings similarly strengthens this conclusion. For example, when Beatriz sued Juan Cansino in the fall of 1558, one of the judges asked her pointedly “why she had not attained her freedom at the same time that the other Indians of Seville” had, clearly implying that most other Indians had already been freed.

20

The greatest legal victory was probably achieved by two Indians who sued none other than Nuño de Guzmán, one of the most influential and ruthless conquistadors in all of Mexico. In the late 1520s and early 1530s, Guzmán’s power rivaled that of even Hernán Cortés. He served as governor of the provinces of Pánuco and Nueva Galicia and presided over the first Audiencia of Mexico. Yet in 1549, two slaves he had brought back to Spain, Pedro and Luisa, had the audacity to sue him. What is more, Pedro and Luisa also demanded 3,000

maravedís

for every year each of them had served since their arrival in Spain in 1539. For someone like Guzmán, under whose watch ten thousand Indians from Pánuco and Nueva Galicia had been sold into slavery, the loss of the legal battle with these two lowly slaves whom he had raised in his home must have been infuriating. But there was little he could do. Through his lawyer, Guzmán sought to reduce the cash award, arguing that “the service provided by the said Pedro and Luisa, and of any other Indian, amounts to very little as they are useful only for minor tasks of little substance, and the work that they perform is not even sufficient to pay for the food and dress and shoes that the said Guzmán has given them.”

21

The New Laws did not end Indian slavery in Spain, but they did initiate the gradual eradication of this peculiar institution in the Iberian

Peninsula. After 1542 it became public knowledge that the king of Spain had freed the Indians of the Americas. Word about Indians suing their masters and scoring legal victories spread quickly. By the 1550s, Indian slaves living in small Spanish towns were well aware that they were entitled to their freedom. Among Spanish owners, the possession of Indian slaves increasingly became an embarrassment and a brazen violation of the law. More tangibly, owners faced greater difficulty in selling their Indians at full price. Indian slaves continued to be exchanged in Spain during the second half of the sixteenth century and even into the early decades of the seventeenth century, but the number of transactions declined steadily until they disappeared almost completely.

22

The Slaves of Early Mexico

The Spanish crown also attempted to end Indian slavery in the New World, but the situation could not have been more different there. Indian slaves constituted a major pillar of the societies and economies of the Americas. In Mexico their importance was evident from the very beginning. No sooner had Hernán Cortés landed on the Gulf of Mexico coast near the site of modern Veracruz in 1519 than he began to anticipate that the lands that he was about to enter would include “many heathen Indians who would wage war on the Spaniards.” Cortés requested permission from the crown to subdue such groups by force and distribute the vanquished Natives as slaves, “as it is customary to do in the lands of the infidels, and it is a very just thing to do.”

23

Cortés’s breathtaking ascent to the Valley of Mexico and eventual conquest of the Aztec empire put millions of Indians nominally under the control of a few thousand Spaniards. Enslaving all of these Natives would have been both impossible and impractical. Instead, Cortés and his men imported the encomienda system from the Caribbean. “The Spaniards went from conquest to conquest, subjecting the land,” explained one friar, “and after each town was taken, a Spaniard would ask Cortés to grant it to him and he then received it as an

encomienda.

” In the Caribbean, the encomienda had failed to protect the Natives from

colonists bent on extracting gold. The encomienda of central Mexico was less insidious. The Indians there were agriculturalists who had long been accustomed to paying tribute. They continued to transfer a portion of their crops and other products to the Spanish encomendero. In return, the Natives remained in their towns and villages and retained a great deal of autonomy. Although abuse was rife, the encomienda of central Mexico was not tantamount to slavery.

24

But Spanish conquerors also acquired slaves, tens of thousands of them. Many were taken from among those who resisted conquest. They were called

esclavos de guerra,

or war slaves. According to one of Cortés’s soldiers who later wrote an eyewitness account, before entering an Indian town Spaniards requested its inhabitants to submit peacefully, “and if they did not come in peace but wished to give us war, we would make them slaves; and we carried with us an iron brand like this one to mark their faces.”

25

The crown authorized Cortés and his soldiers to keep these Indians as long as the conquerors paid the corresponding taxes. Treasury accounts thus offer a few clues about the scope of slave taking in early Mexico. For the period between January 1521 and May 1522—that is, a few months before and after the fall of Tenochtitlán—Spaniards paid taxes on around eight thousand slaves taken just in the Aztec capital and its immediate surroundings. Thousands more flowed from Oaxaca, Michoacán, Tututepec, and as far away as Guatemala as these Indian kingdoms were brought into the Spanish fold. “So great was the haste to make slaves in different parts,” commented Friar Toribio de Benavente (also known as Motolinía) some years later, “that they were brought into Mexico City in great flocks, like sheep, so they could be branded easily.”

26

Besides the slaves taken in military campaigns, Spaniards also purchased Indians who had already been enslaved by other Indians and were regularly offered in markets and streets. They were called

esclavos de rescate,

or ransomed slaves. To distinguish these slaves from those taken in war, the Spaniards used a different type of brand, also applied on the face.

The brand used for “war slaves” resembled the letter

g

, for

guerra

(war). Slaves were usually branded on the cheek or forehead.

The brand used for “ransomed slaves” resembled the letter

r

, for

rescate

(ransom).

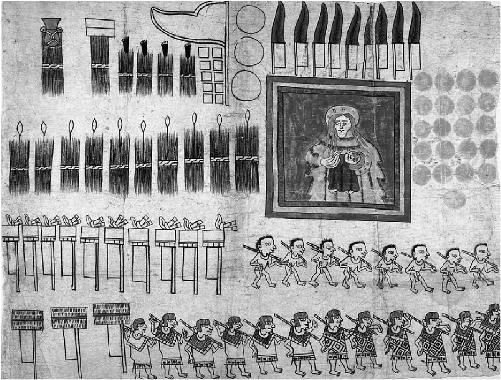

Along with textiles and feathers, Spanish encomenderos occasionally requested Indians as tribute. In 1529 Nuño de Guzmán received eight males and twelve women, all tethered by the neck, from the people of Huejotzinco, as shown in this page from an account book.

Slavery had been practiced in Mexico since time immemorial. Pre-contact Indians had sold their children or even themselves into slavery because they had no food. Many Indians had been sold into slavery by other Indians as punishment for robbery, rape, or other crimes. Some war slaves were set aside for public sacrifices and ritual cannibalism. Some towns even had holding pens where men and women were fattened before the festivities. All of these pre-contact forms of bondage operated in specific cultural contexts. But as Brett Rushforth has recently argued, they were close enough to what Europeans understood as slavery that they persisted into the post-contact period. This was certainly the case in central Mexico, where Spaniards acquired Indians in

tianguis,

open-air markets, for decades after conquest. In the 1520s, these slaves were so plentiful that their average price was only 2 pesos, far less than the price of a horse or cow. Spaniards typically traded small

items such as a knife or piece of cloth in exchange for these human beings. As for their number, we do not have the slightest indication, as these transactions were private and went untaxed.

27

Sixteenth-century Spaniards gave widely different estimates of the overall number of Indian slaves. Las Casas reported that by the middle of the century, more than three million slaves had been made in Mexico, Central America, and Venezuela. The Franciscan friar Toribio de Benavente (who considered Las Casas a “turbulent, injurious, and prejudicial man”) estimated the number of slaves taken in the different provinces of Mexico up to 1555 to be less than two hundred thousand and possibly not even one hundred thousand. It is clear that even at the low end of this range, Indian slaves had become a major portion of Mexico’s workforce.

28

The urgent need for slaves became evident during Mexico’s gold rush in the 1520s. At first Spanish overlords sent their encomienda Indians to the mines, but the Natives resisted this breach of the original encomienda terms. Moreover, after the Caribbean experience, the crown expressly forbade the use of encomienda Indians for mining. Therefore mine owners had to resort to Indian and African slaves organized in work gangs known as cuadrillas.

Notarial documents give us fleeting glimpses of this ruthlessly exploitative world. Fernando Alonso, an ironsmith from Mexico City, and a rancher named Nicolás López de Palacios Rubio formed a partnership to develop a mine in Michoacán. The ironsmith was to contribute crowbars and assorted tools to the operation, along with one hundred Indian slaves—“up to two hundred if possible”—while the rancher agreed to feed these workers for a year. Workers like these became an integral part of the mines where they toiled. They settled down around the mines and performed specialized tasks. In fact, much of the value of a mine was derived from the labor attached to it. As the notarial documents show, all sales of mines included the mine’s slaves. For instance, Pedro González Nájera sold his stake in a mine in Oaxaca in the summer of 1528 and was able to get 600 pesos for it, largely because it had “one hundred slaves taken in a good war and skilled in the work of the mines.” Interestingly, these laborers were both males and females. A 1525 contract between

Pedro de Villalobos and Álvaro Maldonado stipulated that each partner would supply fifty Indian slaves “between men and women.” The sale of one mine involved “sixty Indian slaves, half males and half females,” and another included a clause that allowed the new owner of the mine to select “fifty Indian slaves, 30 males and 20 females, and all aged thirty years or younger.”

29