The Other Slavery (20 page)

Authors: Andrés Reséndez

Governor Felipe Sotelo Osorio (1625–1629) spearheaded the use of Indian auxiliaries to conduct slaving raids. This innovation was fully on display when a group of Vaquero Apaches entered the Spanish town of Santa Fe asking to see “the Mother of God.” The object of the Indians’ curiosity was the statue of the Virgin Mary known as

La Conquistadora,

which had been brought from Spain in 1625. They were led into a crude chapel that harbored the figure, which was carved of solid willow and adorned with a crimson garment covered with golden leaves in arabesque. The leader of the visiting Indians, an elderly man, was so impressed that, “speaking with great devotion,” he declared his intention to become a Christian. What occurred next, however, was hardly edifying. After the Vaquero Apaches departed, Governor Sotelo Osorio “sent for a gutsy Indian captain,” a declared enemy of the visitors, and commanded him and his posse to “bring back whomever they could catch.” They did

as they were told, overtaking the Indians; killing the elderly chief, who was still wearing a rosary around his neck; and bringing a number of captives back to Santa Fe. As one friar summed up this sad episode, the Vaquero Apaches had been on the brink of converting, “but the Devil had recourse to one of his wiles, choosing as his instrument the greed of our governor.”

31

Governor Luis de Rosas (1637–1641) experimented with the use of slaves

within

New Mexico to manufacture goods for export to Parral. He set up an

obraje,

or textile sweatshop, in Santa Fe, where he kept some thirty Indians locked up. These Indians, seized in “unjust wars,” according to one resident, made stockings and other woolen items and painted

mantas

(cloths) with charcoal. Governor Rosas was a hands-on owner; he could be frequently found at the shop covered with charcoal, “and one could tell him apart from the Indians only by his fine clothes.” Working conditions in

obrajes

all over Mexico ranged from bad to appalling, and those in New Mexico were no different. Although some of Governor Rosas’s Indians died of starvation, the governor had the good business sense to replace them by expanding the Spaniards’ war with the Apaches and Utes. By calling for unprovoked attacks on the Indians, Governor Rosas initiated a cycle of reprisals and counter-reprisals that resulted in ideal conditions for obtaining Indian workers, some of whom ended their days in his textile shop.

32

We have seen that the demand for Indian slaves increased markedly in the wake of the Indian rebellions around Parral in the 1650s. Governor Juan Manso (1656–1659) rose to the occasion. This frontier entrepreneur took his predecessors’ policies to the next logical level by issuing a “definitive death sentence against the entire Apache nation and others of the same ilk.” In other words, he declared open season on all Apaches and their allies. At the same time, Governor Manso devised a legal framework to bypass the crown’s prohibition against Indian slavery. He gave out certificates that entitled the bearers to keep Apaches “in deposit”—not as slaves—for a specified number of years. “The Apaches have been irreducible enemies of our Catholic faith and of all Christians of this kingdom,” read one of these certificates signed in Santa Fe on October 12, 1658, “and by virtue of this sentence they may be taken out of

this kingdom [New Mexico] and kept in deposit for a period of fifteen years starting on the day when they reach twelve years of age, and at no time would they be able to come back to this kingdom.” This particular certificate was issued for Sebastián, a seven-year-old boy with big black eyes and a face scarred by smallpox.

33

We can get a good sense of Parral’s gravitational pull on New Mexico in Governor Bernardo López de Mendizábal’s frantic preparations as he readied nine wagons for departure for the mining center in the fall of 1659. As an incoming governor eager to profit from his position of authority, Mendizábal first dispatched a squadron to bring back “heathen Indians” to sell. They collected about seventy Natives. Governor Mendizábal also sent orders to six pueblos in the Salinas area “to carry salt on their shoulders and on their own animals” for a distance of up to thirty leagues (ninety miles) without pay. A captain left a vivid description of Mendizábal’s exertions in a letter worth quoting at length:

This sending of salt to El Parral by the governor is injurious, Sir, because, to equip his wagons with some degree of safety, he forthwith sent his

alcaldes mayores

[higher magistrates] (who are people of ordinary sorts, only concerned with promoting their own interests), to some of the pueblos to take away from the natives their grass mats, which were the only beds they had, giving them nothing in exchange. From others they took their buckskins and their

tecoas

(which are pieces of dressed leather that they use for footwear). The

alcaldes

use these things to cover their wagons. We have evidence that in the pueblo of Taos alone, they took forty buckskins without any pay whatsoever.

34

Clearly by the 1650s, the kingdom of New Mexico had become little more than a supply center for Parral.

From the preceding examples and many others, it is possible to reconstruct the overall trajectory of the traffic of Natives from New Mexico. The earliest Spanish settlers began by enslaving Pueblo Indians. But they quickly discovered that keeping Pueblos as slaves was counterproductive, as this bred discontent among the Natives on which Spaniards depended for their very sustenance. Although the occasional

enslavement of Pueblos continued throughout the seventeenth century, the colonists gradually redirected their slaving activities to Apaches and Utes. The Spaniards injected themselves into the struggles between different

rancherías

(local bands) and exploited intergroup antagonisms to facilitate the supply of slaves, as Governor Sotelo Osorio did with the “gutsy Indian captain.”

35

Although New Mexican governors played the leading role in developing the slave trade and controlling the lion’s share of the proceeds, private entrepreneurs also gained a foothold in the business. Colonists who owned encomiendas were able to extract unpaid labor from their Pueblo Indians and, as one witness admitted, occasionally send some of them away “to be sold as slaves in New Spain, as was the practice.” Spanish settlers without encomiendas were at a clear disadvantage concerning the commercial opportunities of the silver economy. But they could still acquire Indian captives/servants, whom they could sell in more southerly markets or keep in New Mexico to produce export goods. From the start, New Mexican colonists possessed an extraordinarily high number of servants. Already in 1630 Santa Fe’s minuscule white population of about 250 held around 700 servants and slaves; that is, every white man, woman, and child residing in the capital possessed between two and three Native servants on average. These Indians, Pueblos as well as Plains Indians acquired through slave raids, toiled in sweatshops or private homes weaving and decorating textiles, preparing hides, and harvesting pine nuts.

36

The growing number of New Mexican Indians in Parral can be gleaned from baptismal records, which contain entries such as these: “Inés, baptized on April 16, 1671, Indian girl from New Mexico of unknown parents,

criada

of Ensign Lorenzo Samaniego”; and “Antonia, baptized on May 7, 1674, Apache girl of unknown parents from the hacienda of Captain Andrés del Hierro.” Even though parish records refer to them as

criadas

(servants) rather than

esclavas

(slaves), everyone in Parral knew that they had been acquired in public auctions at the main plaza. The number of New Mexican slaves sent to Parral increased in the 1650s, continued to expand in the 1660s, and reached record numbers in the 1670s (see

appendix 5

).

37

By 1679 so many Indians were flowing out of New Mexico that the bishop of Durango launched a formal investigation into this burgeoning business. Bishop Bartolomé García de Escañuela undertook this inquest less out of a sense of moral or religious duty than out of concern about the church’s declining revenues. Ordinarily, the faithful of Nueva Vizcaya—a province that included the modern states of Chihuahua, Durango, Sonora, and Sinaloa—had to pay a yearly tithe to the bishopric of ten percent of their animals and crops. But ranchers all over this region discovered that they were able to reduce their herds—and consequently their tax liabilities—by trading tithe-bearing animals for Indian slaves, who were tax-free. In effect, the acquisition of Indians amounted to a tax shelter, and the amount of the sheltered revenue was large enough that the tithes of the bishopric of Durango were declining. As Bishop Escañuela toured his enormous ecclesiastical district, he interviewed merchants and slave traffickers from New Mexico to learn more about the human traffic. One outspoken young man named Antonio García explained that no merchant could leave New Mexico on his own because the Indians around El Paso del Norte were at war with the Spaniards, “so when the governor sends his Indians and his merchandise to this bishopric of Nueva Vizcaya, he invites everyone to come together in a convoy.” García himself had joined the convoy in the fall of 1678. On that occasion, he had taken three Indian girls and had received fifteen or sixteen mares for each of them. He was a small merchant compared with one of his traveling companions, who had exchanged his human cargo for more than a thousand cows. The consequences of this trafficking were not long in coming. In the summer of 1680, the Indians of New Mexico launched a massive rebellion, which, as we will see in

chapter 6

, was motivated to a large extent by the growing Indian slave trade.

38

Beyond northern Mexico, coerced Indian labor played a fundamental role in the mining economies of Central America, the Caribbean, Colombia, Venezuela, the Andean region, and Brazil. Yet the specific arrangements varied from place to place. Unlike Mexico’s silver economy, scattered in multiple mining centers, the enormous mine of Potosí dwarfed all others in the Andes. To satisfy the labor needs of this

“mountain of silver,” Spanish authorities instituted a gargantuan system of draft labor known as the

mita,

which required that more than two hundred Indian communities spanning a large area in modern-day Peru and Bolivia send one-seventh of their adult population to work in the mines of Potosí, Huancavelica, and Cailloma. In any given year, ten thousand Indians or more had to take their turns working in the mines. This state-directed system began in 1573 and remained in operation for 250 years. Other mines of Latin America, such as the gold and diamond fields of Brazil and the emerald mines of Colombia, depended more on itinerant prospectors and private forms of labor. But even though the degree of state involvement and the scale of these operations varied from place to place, they all relied on labor arrangements that ran the gamut from clear slave labor (African, Indian, and occasionally Asian); to semi-coercive institutions and practices such as encomiendas, repartimientos, debt peonage, and the

mita;

to salaried work. Mines all across the hemisphere thus propelled the other slavery.

39

5

The Spanish Campaign

A

CENTURY BEFORE THE

American and French Revolutions, the Spanish crown set out to free the slaves around the world. The intended beneficiaries were not Africans but Indians living in the far corners of the empire. And the leaders of this crusade were not fiery revolutionaries but a mystical king, his foreign-born queen, and their sickly son.

1

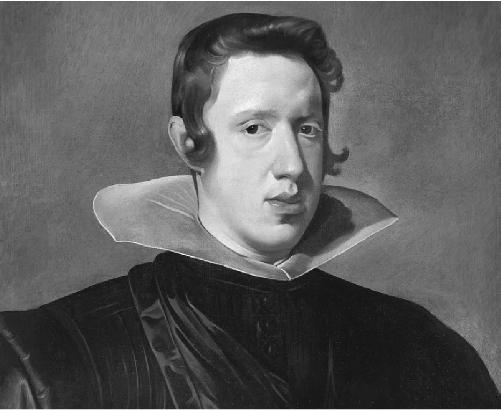

This movement began with one of the least likely figures to get embroiled in an idealist quest. Philip IV was a worldly man fond of hunting, bullfighting, and the arts. Of all the Spanish monarchs, he stands as the most avid and discerning collector and patron of painters, beginning with his own court painter, the extraordinary Diego Velázquez. But Philip’s true passion, like that of many of his contemporaries, was the theater. In his youth, he was a regular at the

corrales,

or theaters, of Madrid, enjoying the latest plays by the prolific Lope de Vega, the cantankerous Francisco de Quevedo, or some other luminary of Spain’s Siglo de Oro (Golden Age). Since court etiquette prevented kings from going to the theater, Philip attended incognito, often wearing a mask. Plays were represented in courtyards surrounded by houses overlooking the stage. In one of these second-floor apartments, above the crush and din of the crowd, the Spanish king was able to spend many pleasurable afternoons taking in comedies or dramas without being noticed.

2