The Other Slavery (22 page)

Authors: Andrés Reséndez

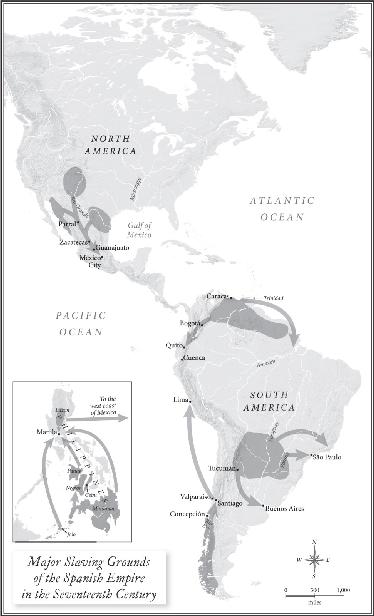

Across the Andes, a second major slaving zone extended through the provinces of Paraguay, Tucumán, and adjacent areas. In the 1660s and 1670s, Spanish slavers staged raids in the Calchaquí Valleys, an area in Tucumán of stunning rock formations and forbidding gorges, where various Indian groups had coexisted since pre-contact times and were now being hunted down and shipped throughout the Río de la Plata basin. The Spaniards were not the only ones raiding in this area. From the coast of Brazil, small parties of

bandeirantes

—a cross between pathfinders, prospectors, and slavers—also mounted devastating expeditions into the interior. Over the centuries, Brazilians have celebrated the

bandeirantes

in poems, novels, and sculptures, hailing them as the founders of the nation. Yet the

bandeirantes

took upwards of sixty thousand captives in the middle decades of the seventeenth century, snatching mostly Indians congregated in the Jesuit missions of Paraguay.

14

The llanos of Colombia and Venezuela, the vast grasslands crisscrossed by tributaries of the Orinoco River, were a third zone of enslavement. Here Spanish traffickers competed with English, French, and above all Dutch networks of enslavement, all of which operated in the llanos. Interestingly, the Carib Indians—whom the Spaniards had long sought to exterminate—emerged as the preeminent suppliers of slaves to all of these European competitors of the Spanish. The Caribs carried out raids at night, surrounding entire villages and carrying off the children. A Spanish report summed up these activities: “It will not be too much to say that the Caribs sell yearly more than three hundred children, leaving murdered in their houses more than four hundred adults, for the Dutch do not like to buy the latter because they well know that, being grown up, they will escape.” The victims of this trade could variously wind up in the Spanish haciendas of Trinidad, the English plantations of Jamaica, the Dutch towns of Guyana, or as far west as Quito, Ecuador, where some of them toiled in the textile sweatshops for which this city was famous.

15

A fourth major slaving ground lay in northern Mexico. “There is nothing more forbidden since the beginning of conquest than Indian slavery,” pithily began a report that Queen Mariana received from a member of the Audiencia of Guadalajara, “yet it is very common to see slaves being sold and held in these provinces, especially the Chichimecs of Sinaloa, New Mexico, and Nuevo León.” As we have seen, this large

and internally fragmented slaving area supplied laborers to the ranches, silver mines, and towns of northern Mexico and as far south as Mexico City.

16

The last major area of enslavement, and perhaps the largest, was in the Philippines, where Europeans had stumbled on a dazzling world of slaves. “Some are captured in wars that different villages wage against each other,” wrote Guido de Lavezaris seven years after the Spanish had first settled in the Philippines, “some are slaves from birth and their origin is not known because their fathers, grandfathers, and ancestors were also slaves,” and others became enslaved “on account of minor transgressions regarding some of their rites and ceremonies or for not coming quickly enough at the summons of a chief or some other such thing.” Traffickers also targeted the Muslim-dominated islands in the southern part of the archipelago, such as Mindanao and Jolo, or the dark-skinned Negritos or Negrillos—equivalent to sub-Saharan Africans in the eyes of many slavers—who inhabited the islands of Negros, Panay, and Cebu. A variety of slaves were offered in the markets of Manila, and many were transported across the Pacific on the Spanish galleons bound for Mexico and delivered to their owners there.

17

Slavery was not new in these five major regions of enslavement. All of them possessed traditions of Indian-on-Indian bondage harking back to pre-contact times. Yet with the arrival of white colonists, these varied traditions of captivity were subsumed under the blanket term

esclavitud,

or slavery. Highly ritualized, idiosyncratic, and regional practices of bondage gradually became adapted to suit the needs of white colonists. Thus the traffic of Natives became commodified and expanded geographically. Apaches from New Mexico were sold as far south as central Mexico and eventually into the Caribbean. Mapuches from southern Chile, accustomed to cold or temperate climates, were marched to the port of Valparaíso and transported by ship to the scorching coastal plains of Peru. And Filipinos crossed the Pacific Ocean to reach their final destination in America. These forced migrations spanning hundreds or even thousands of miles, and the slaving networks that made such long-distance transactions possible, were unthinkable before the arrival of Europeans.

18

Freeing the Indians

The start of the Spanish antislavery crusade cannot be dated with precision. It began somewhat nebulously as Philip addressed the insurrection in Chile in 1655 and attempted to clear his royal conscience by issuing a raft of orders curtailing the enslavement of Indians. But the ailing king’s approach was gradualist and the pace too slow. His correspondence with viceroys, governors, and bishops stretched over months and years and dragged on until his death in 1665. Queen Mariana brought renewed energy to the abolitionist crusade. If we had to choose an opening salvo, it would be the queen’s 1667 order freeing all Chilean Indians who had been taken to Peru. Her order was published in the plazas of Lima and required all Peruvian slave owners to “turn their Indian slaves loose at the first opportunity.” When the viceroy of Peru learned of this order, he could not hide his disbelief. He praised “the royal clemency of Her Majesty” but went on to write a long letter explaining “the dire consequences” of an order that would “reignite the war in Chile” and allow the freed Indians to “go back to their heathen rituals and preserve their ferocious character.” The viceroy’s letter conveyed the unmistakable sense that the queen was a well-meaning lady but completely unaware of the realities of the New World.

19

As she gained experience and confidence, Mariana became bolder. In 1672 she freed the Indian slaves of Mexico, irrespective of their provenance or the circumstances of their enslavement. Her decree of emancipation fell like a thunderbolt on a clear day, as we shall see later in this chapter. Two years later, Mariana seized on an unexpected message from the outside to strike again. In October 1674, the papal nuncio to Spain wrote that “the groans of the poor Indians of Chile, who have been reduced to miserable slavery with various pretexts by the political and military authorities of that kingdom, have reached the ears of the Holy Father,” and he wondered why slavery persisted in Chile “in spite of the many and repeated edicts of the most powerful Kings, predecessors of Your Majesty, and of the orders of the Holy Faith.” Mariana and her councilors waited only a few weeks to respond, banning all forms of slavery in Chile. They extended the same prohibition to the Calchaquí

Valleys on the other side of the Andes. The campaign to liberate the Indians had kicked into high gear.

20

With the accession of Charles II to the throne in 1675, the antislavery crusade neared its culmination. In 1676 Charles set free the Indian slaves of the Audiencia of Santo Domingo (comprising not only the Caribbean islands but some coastal areas as well) and Paraguay. Finally, on June 12, 1679, he issued a decree of continental scope: “No Indians of my Western Indies, Islands, and Mainland of the Ocean Sea, under any circumstance or pretext can be held as slaves; instead they will be treated as my vassals who have contributed so much to the greatness of my dominions, and I will remain very vigilant and careful because this is a very grave matter.” In a separate order issued on the same day, el Hechizado freed the slaves of the Philippines, thus completing the project initiated by his father and mother of setting free all Indian slaves within the Spanish empire, a clear—if unacknowledged—milestone in the long and checkered history of our human rights.

21

The most detailed pronouncement of the Spanish monarchy with respect to the enslavement of Indians appears in the monumental compilation of laws of the Spanish colonies known as the

Recopilación de las leyes de Indias,

an attempt at legal systematization that required decades of painstaking work before its publication in 1680. One section of the

Recopilación

is devoted to the freedom of the Indians, emphatically prohibiting their enslavement under all circumstances, even if taken in just wars or ransomed from other Indians. Unlike the French and American revolutionaries of the late eighteenth century, however, the Spanish monarchs did not arrive at the notion of “self-evident” or “inalienable” rights that applied in all cases and at all times. Instead, considering each case on its own merits, they consented on occasion to the enslavement of some of their most recalcitrant subjects. And thus the

Recopilación

prohibited the enslavement of Indians “except when expressly permitted in this same legal compendium.” As it turned out, they excluded two groups from their broad royal protection: the inhabitants of the island of Mindanao in the Philippines, “who have taken up the sect of Muhamad and are against our Church and empire,” and the Carib Indians, “who attack our settlements and eat human flesh.”

22

In principle, Philip, Mariana, and Charles were free to rule the colonies of the empire as they saw fit. They issued one decree after another, expecting prompt and dutiful compliance, as if they could change everything with the scratch of a pen. We may doubt the efficacy of their method—the Spanish monarchs themselves were not so naive as to think that this would happen in every case—but their direct orders did carry enormous weight. In Trinidad, for example, Governor Sebastián de Roteta wrote to King Charles, “After several pleas and predictions of the utter destruction of this island, of its poverty, and of the benefits to the Indians themselves who are much better off enslaved than eaten by the Carib Indians, and disregarding the accidents and dangers that I faced on account of such a great novelty, my resolve was to comply entirely with Your Majesty’s royal orders.”

23

Governor Roteta requested that all residents of the capital city of San José de Oruña, as well as those of other outlying settlements, bring their Indians to the governor’s house. Failure to report each slave would be punished with a fine of 100 pesos (roughly the market value of an Indian). Roteta then compiled a list of all the slaves turned over and recorded each one’s name, age, place of origin, and former masters before setting them free. He began the list with the thirteen Indians who had served as domestics in his own household. Other prominent residents followed suit: Vicar Alonso de Lerma presented four Indians, Father Andrés de Noriega gave up another four, Sergeant Major Don Pedro Fernández brought ten, and so on. In all, they surrendered 334 slaves. The brief biographical information contained in the slave list provides an inkling of the ravages of the slave trade in the llanos: “Diego, 20 of age, Indian from the missions of Píritu in the province of Cumaná (coast of Venezuela)”; “Teresa, 25, Carib Indian from the Caura in the Orinoco River”; “Pedro, 22, Indian from the Dutch town of Berbis [Berbice] at the mouth of the Orinoco River.” The vast majority said they had come from “the town of Casanare,” which was nothing but a crude port at the mouth of the Casanare River on the coast of Colombia from which the slaves from the interior were shipped to Trinidad. Many of them were young children when they were enslaved and no longer remembered the names of the towns and communities of their parents.

All of these Natives found themselves suddenly and unexpectedly free. In addition to prying them loose from their masters, Governor Roteta made sure to wipe out their debts, saying that doing otherwise would have been “an even greater burden than leaving them as slaves.” As would happen upon the abolition of African slavery in the United States and Britain, some Indian slaves chose to stay with their former masters, but many decided to live independently. They were happy to receive plots of land at some distance from San José de Oruña where they attempted to remake their lives. This group consisted mostly of women and children “in a miserable state” who could not understand one another, as they spoke different languages. Within a few months, however, they had built thirty or forty shacks clustered in two pueblos. Their fate is unknown.

In other parts of the empire, the campaign generated excitement but also tremendous opposition. In Mexico, Fernando de Haro y Monterroso, a member of the Audiencia of Guadalajara, became the moving spirit of the crusade. He publicized the queen’s antislavery decrees, heard complaints from mistreated Indians, and wrestled with “powerful personages over the issue of the personal service of the Indians.” Nothing in Haro y Monterroso’s history as a sober and conscientious lawyer would predict his antislavery ardor. His persistent letter writing to governors and alcaldes (magistrates) secured the release of close to three hundred Indian slaves, as well as five “Chinese” slaves from the Philippines in Guadalajara. Furthermore, buoyed by these early victories, Haro y Monterroso requested the expansion of the campaign. “My actions are not enough if we do not do the same in the Audiencias of Mexico and Guatemala,” he wrote to Queen Mariana, “because these provinces [Sinaloa, New Mexico, and Nuevo León] are so large and the Indians have so little spirit that they are often sold in other jurisdictions.” The queen and the members of the Council of the Indies were only too glad to dispatch the necessary orders.

24