Authors: Andrés Reséndez

The Other Slavery (39 page)

Mexican ranchers pioneered the other slavery in California, but American colonists readily adapted to it. They acquired properties of their own and faced the age-old problem of finding laborers. Their options were limited. No black slaves existed in California, at least not in the open, as Mexico’s national government had abolished African slavery in 1829. Asian workers were still rare. In the early 1840s, Don Guadalupe kept four Native Hawaiians at Rancho Petaluma, as did a neighboring American rancher named John Sinclair and some others. The “coolie” (Asian) trade began after the gold discoveries of 1848 and would reach significant numbers only years later. Indian labor was the only viable option. Although the indigenous population of Alta California had been cut by half during the Spanish and Mexican periods—roughly from 300,000 to 150,000—Indians still comprised the most abundant

pool of laborers. Short of working the land themselves, white owners had to rely on them.

15

Traces of the earliest Euro-American settlers are still visible in northern California. John Sutter was the proprietor of a large fort by the junction of the Sacramento and American Rivers that is now a major tourist attraction in midtown Sacramento. George C. Yount was the first Euro-American to settle permanently in the Napa Valley; the wine-sipping town of Yountville is named after him. Pierson B. Reading was the recipient of a huge land grant that would give rise to the city of Redding. And Andrew Kelsey, a ruthless entrepreneur, built a ranching operation just south of Clear Lake that is now the town of Kelseyville. These foreigners were acquisitive, possessed good business sense, and were quick to appreciate the advantages of coerced Indian labor.

Josiah Belden, a member of the first wagon train of Americans traveling from Missouri to California, characterized the local Indians as “primitive and inoffensive” and observed that their apprenticeship in the Spanish missions had made them “very useful servants and laboring men for the rancheros and citizens.” John Bidwell of the same group pointed out that it was possible to employ “any number of Indians by giving them a lump of Beef every week, and paying them about one dollar for same time.” A Massachusetts doctor named John Marsh offered clearer guidance on how to treat Indian workers: “Nothing more is necessary for their complete subjugation but kindness in the beginning, and a little well timed severity when manifestly deserved.” And even when the latter method became a necessity, Dr. Marsh reassured his readers, the California Indians “submit to flagellation with more humility than the negroes.”

16

Perhaps no one expressed the views and opinions of that first generation of American settlers better than Lansford W. Hastings, author of

The

Emigrants’ Guide to Oregon and California,

published in 1845. In a heady mix of boosterism and insight, Hastings first waxed lyrical about California’s valleys “of unequalled fertility and exuberance,” its “unheard of uniformity and salubrity of climate,” and its “inexhaustible resources,” so that no country is “so eminently calculated by nature itself, in all respects, to promote the unbounded happiness and

prosperity of civilized and enlightened man.” According to Hastings, the only disquieting aspect of California was that the local Indians were “in a state of absolute vassalage, even more degrading and more oppressive than that of our slaves in the south.” Luckily, even this problem could be turned into an advantage: “Whether slavery will eventually be tolerated in this country in any form, I do not pretend to say, but it is quite certain that the labor of Indians will for many years be as little expensive to the farmers of that country, as slave labor, being procured for a mere nominal consideration.”

17

There is no question that Americans benefited from the peonage system, but there were significant differences in how they put it into practice. On one end of the spectrum were the decidedly paternalistic

patrones

(landowners), such as John Bidwell. In several expeditions through northern California, he became acquainted with Natives living on ranches and at large. The fact that he was fluent in Spanish and learned several Indian words greatly facilitated communication. Like many other owners, Bidwell regarded Indians as children of nature—credulous, superstitious, and gullible—and sometimes resorted to manipulation. To intimidate them, he carried the paw of a very large grizzly bear and showed it to them, knowing that they viewed grizzlies as especially powerful, and even evil, spirits. He also told them that he would become very angry if they came near his camp when he slept and would command the lightning to fall on them.

18

Bidwell’s need for Indian workers became critical during the gold rush years. He was among the lucky few who struck gold and was able to establish a productive gold-mining camp on the Feather River. During the frantic mining seasons of 1848 and 1849, he and his partners managed to recruit between twenty and fifty Natives from the Butte County area, including some Mechoopda Indians with whom he retained a lifelong association. Through his good fortune and their efforts, Bidwell amassed a fortune in a short time. He was a pragmatist who used his personal rapport with the Indians and his provisions to his advantage. Bidwell paid his workers with food and clothing rather than cash, but to his credit, he did not use debt or coercion to get his way. In fact, when he served as alcalde at the mission of San Luis Rey a few years earlier, he

specifically refused to return fugitive workers to their Mexican masters because of unpaid debts.

19

Bidwell’s peculiar blend of pragmatism and paternalism was perhaps best expressed at Rancho del Arroyo Chico, a 22,000-acre property east of the Sacramento River and north of Chico Creek (encompassing what is now the town of Chico) that he had acquired with his mining wealth. When he first moved onto the ranch in 1849, there were no Indians on the premises. Therefore his first goal was to convince the Mechoopda Indians living immediately to the south to come to his ranch. Bidwell gave them work and asked them to stay. He offered the ranch as a refuge where they could hunt, fish, gather acorns, conduct communal grasshopper drives, and generally maintain their way of life and culture at a time of rapid change throughout California. A couple of hundred Mechoopdas resettled in a new ranchería barely one hundred yards from Bidwell’s residence. One visitor commented that Bidwell had found these Indians “as wild as a deer and wholly unclad,” but through his protection and employment, they had built “happy homes with their own gardens, fruit trees, and flowers.” With the passage of time, they erected bark huts and even some adobe structures arranged in the shape of a cross.

20

It is difficult to gauge the exact nature of the ties between this American

patrón

and the resident workers. An article that appeared in the

Yreka Semi-Weekly Union

in 1864 accused Bidwell of keeping “a slave pen” at Rancho Chico and alluded to an incident in which an Indian man had been beaten with a club while his hands and feet were tied together over a barrel. The article urged Bidwell to stop the hypocrisy of supporting the abolition of black slavery while at the same time enslaving Indians. For his part, Bidwell contended that the Natives at Rancho Chico had never been profitable to him and that his only objective had been to protect them. The record makes clear that this was disingenuous: Bidwell derived tangible advantages by having a stable workforce on-site. At the same time, he protected “his Indians” on more than one occasion. In one dramatic instance in July 1863, he defended the ranch Indians when they were accused of the brutal killing of two white

children nearby. He even faced an armed mob led by the outraged father, Samuel Lewis, and went so far as to call out the army rather than allow his resident Indians to be murdered or driven away.

21

The last phase in the evolving relations between Bidwell and the Mechoopdas began in 1868, when the aging owner married Annie Kennedy, a young, socially active woman who was also a devout Presbyterian. For the past twenty years, Bidwell and the Mechoopdas had forged a mutually convenient arrangement, with the Indians providing some services for him around Rancho Chico while still being able to retain much of their culture. The close ties between protector and protected are best illustrated by Nopanny, an Indian woman in her late twenties or early thirties who worked for Bidwell as a cook and housekeeper. Bidwell enjoyed Nopanny’s cooking, including her grasshopper cakes, which he proudly offered to his guests. Nopanny also served as a key intermediary between the American rancher and the Mechoopdas. When Annie Bidwell began to take control of the household after 1868, Nopanny reportedly confronted her and tried to put her in her place: “No, me Mrs. Bidwell number one, you Mrs. Bidwell number two.” Although it is not possible to confirm the accuracy of this exchange and one can only speculate about the true nature of the relationship between John Bidwell and Nopanny, we do know that Annie Bidwell did not let things stand. She replaced all the Indian house servants with Chinese cooks and Irish maids.

The changes did not stop there. When the Mechoopdas disturbed Annie’s sleep with their mourning ceremonies, which lasted late into the night, she had the entire ranchería moved to another site about a mile away from the house. Annie also set out to instruct a group of Natives whom she regarded as much too wild. Her civilizing and religious campaigns especially targeted the children but also were aimed at a few adults. One of Annie’s pupils, Elmer La Fonso, gained some fame in the community for singing gospel songs “with a fine baritone voice.” A blind Indian named Austin McLain became a violin player, and a group of Natives formed a brass band that played in the Fourth of July parade and at other celebrations. In the end, upon her death in 1918, Annie Bidwell

deeded twenty-eight acres of land to the ranchería. This final act of generosity, however, failed to provide a stable home for the Mechoopdas. Eventually the federal government took over the land Annie had left to them.

22

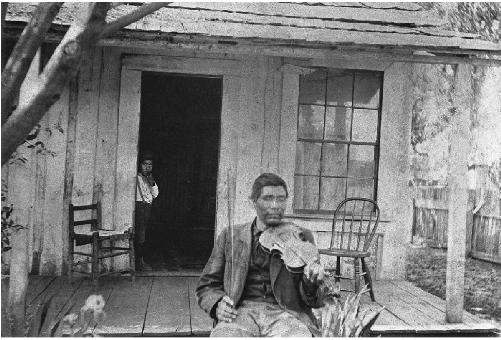

A blind Indian named Austin McLain plays the violin in front of a home in the Chico Ranchería.

If Bidwell was a relatively benevolent

patrón,

Captain John Sutter was the personification of the hard-driving frontier entrepreneur. From the time of his arrival in California in 1839, this Swiss-born officer was bent on carving out an empire for himself. As he put it, “I preferred a country where I should be absolute master.” Carrying an armful of letters of introduction and surrounded by his European and Hawaiian employees, Sutter took pains to project an aura of confidence, wealth, and far-reaching vision. His theatrics must have worked on some level. In short order, he obtained a grant from the California government, selected a propitious embankment by the Sacramento River, and began building an establishment that looked more like a fort than a farm. He was soon able to parlay his meager resources into an impressive enterprise.

23

A Swedish doctor named Sandels visited Sutter’s fort in 1843, four years after it was built. Dr. Sandels was taken by the beauty of the landscape as he ascended the Sacramento River, with its many turns and lush canopies on both sides. He also was impressed by the scale of Sutter’s building, a two-story quadrangular adobe structure enclosing a very large area. Dr. Sandels arrived very early in the morning and found Captain Sutter already issuing orders for the day. It was time for the wheat harvest, and the place was bustling, as several hundred Indians “flocked in” for their morning meal. They rushed toward several troughs made of hollowed-out tree trunks in the middle of the patio. Crouching on their haunches, they reached into the troughs with their bare hands to scoop up a thin porridge, which they quickly stuffed into their mouths. “I must confess I could not reconcile my feelings to see these fellows,” Dr. Sandels would later write in his memoir, “as they fed more like beasts than human beings.” After having “half satisfied their physical wants,” they were given sickles and hooks and driven off to the fields.

24

To fellow Euro-Americans, Captain Sutter came across as an affable frontiersman, frank and generous. But his outsize ambitions also made him imperious and demanding toward his dependents. To sustain his fort, Sutter bought cattle and foodstuffs on credit from his neighbors. Indeed, throughout his life the Swiss officer had shown a propensity to take on more debt than was prudent. “He would perhaps have bought anything at any price if it could be obtained on credit,” opined the nineteenth-century historian Hubert Howe Bancroft. And in 1841, the already overextended Sutter was presented with the buying opportunity of a lifetime.

25