The Other Slavery (36 page)

Authors: Andrés Reséndez

More commonly, comancheros ransomed captives to resell them at a higher price. Traditionally, they had acquired captives held by Comanches, Apaches, and other Indians and resold them as chattel in New Mexico. With the rise in the number of Mexicans taken in the nineteenth century, comancheros simply folded this new stream of captives into their business. Americans on the frontier marveled at how these merchants treated their own kith and kin as chattel. Comancheros sometimes justified the acquisition of these captives by citing their compassion for fellow Christians stranded among heathens. In spite of this pious posturing, in reality such “ransomed” individuals had now become the property of their “redeemers” and were certainly not free to return home. Instead, the comanchero was now in a position to negotiate another “ransom” with the captive’s family or attempt to resell him or her at a higher price.

Remarkably, some comancheros may actually have specialized in the traffic of Mexican captives, as the Mexican government discovered while investigating the case of the Frescas family. Juan José Frescas and his nine-year-old son, Concepción, had been out cutting wood near

Chihuahua City when a party of Indians attacked them in the summer of 1845, killing the father and taking the boy. He was “a blond, long-faced, chubby boy with a big nose,” easy to recognize. For three months, the mother made inquiries, until she learned that her son was being held by a man named Juan Gutiérrez, who lived in the little town of Padillas, near Socorro, in southern New Mexico. Further investigations revealed that Gutiérrez held not only Concepción but also “many others because he takes part in that type of traffic.” Gutiérrez “ransomed” most of his Mexican captives from the Apaches. Other merchants, the governor of New Mexico ruefully admitted, conducted a similar traffic with Comanches and Navajos.

20

These cases emphasize the complicity of all ethnicities in the captive exchange that flourished along the border. The line separating captors from captives was blurry. We tend to think of Indians, Mexicans, and Anglo-Americans as self-contained billiard balls colliding with one another on the frontier. In reality, however, one-fourth of all Kiowa Indians and nearly half of all Comanches were of Mexican descent, and many of them surely participated in raids against fellow Mexicans. Conversely, some Mexican communities, such as San Carlos, in Chihuahua, were notorious for acquiring the spoils offered by Indians—including captives taken elsewhere in Mexico—in much the same way that Bent’s Fort on the Arkansas River “ransomed” captives to work there and New Mexico absorbed goods and individuals stolen by Indians in Chihuahua. It is clear that in the harsh frontier environment, ethnic and national loyalties frequently mattered less than the glint of profit and the imperative of survival.

21

A Family Story

The Apaches were transformed by the general breakdown in Mexico’s control of the border. Although their experience resembled that of the Comanches, it also differed in some crucial respects. In colonial times, the Apaches had been among the worst victims of enslavement. In the seventeenth century, they had been forcibly transported to the silver

mines of northern Mexico, and in the eighteenth century they had suffered in colleras bound for Mexico City and the Caribbean. But with the end of the silver boom, their ordeal came to a halt. The colleras ceased after 1816 as the presidios declined or were abandoned altogether.

22

The celebrated Chiricahua Apache chief Geronimo and his family lived through these searing transitions in western New Mexico and eastern Arizona. Geronimo’s grandfather, Mahco, had been chief of the Bedonkohe band at the height of Spanish militarization of the frontier. The presidios in Chihuahua and Sonora had exerted so much pressure on the Chiricahua Apaches that many of them sued for peace in the 1780s. Threatened by the horror of enslavement and deportation, they agreed to settle in fixed communities under the watchful eye of Spanish officials. Thus began a thirty-year social engineering experiment. The Spaniards gave seeds, animals, farming tools, and even firearms to the Apaches, and in return they were expected to become sedentary agriculturalists. The transition was never complete. The settled Apaches continued to move around, hunting, gathering, and even raiding on occasion, doing their best to maintain their traditional way of life. But they did become more reliant on crops and more dependent on Spanish clothes, weapons, and ammunition. Mahco was remembered as “a man of peace and a successful rancher” who enjoyed “good repute among the Mexicans.” Much of his life coincided with this extraordinary period of relative calm.

23

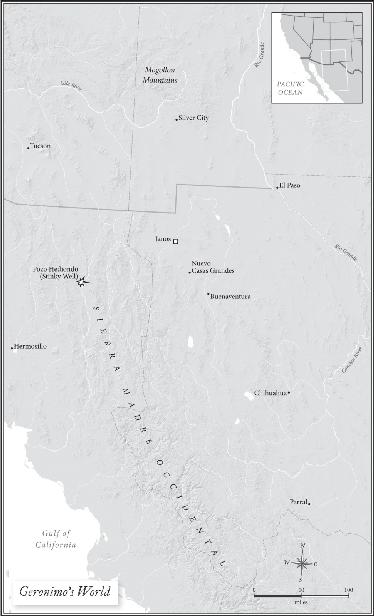

Yet these Indian settlements depended on the continuing flow of money and the presence of the military. Mexico’s struggles for independence eroded both of these pillars. The annual expenditures at the presidio of Janos—the closest to the Bedonkohe band—plummeted by more than ninety percent. The number of soldiers and the overall civilian population residing at the garrison also declined significantly in the 1820s. As had happened elsewhere along the frontier, Mexico’s prolonged wars and economic ruin fanned the fires of change. Geronimo was born around 1823, barely two years after Mexico’s independence. As the country’s defenses crumbled, the Bedonkohe people abandoned their settlements and retreated into New Mexico’s Mogollon Mountains, a compact, extremely rugged range thirty miles in length. Peaks soaring above ten thousand feet, deep canyons and gorges, and mesas buffeted by strong winds and violent storms offered these Apaches a nearly impregnable refuge, as well as immediate access to various Mexican communities and ranches.

24

During Geronimo’s youth, no single individual led the Chiricahua Apaches, or even the Bedonkohe band, which was further subdivided into local groups and extended families, each with its own chief. But there was one warrior who captured the imagination of many young Apaches. The Mexicans knew him as Fuerte (Strong) or Mangas Coloradas (Red Sleeves). At six feet five inches tall, he towered above other Apaches and Mexicans alike. He was “clothed with muscles,” according to the enthusiastic description of an American physician, and had deep-set dark eyes and a posture as “straight as a reed from which his arrows were made.” This formidable man helped pioneer a new relationship between the Chiricahuas and Mexico. In one of his earliest raids, probably between 1812 and 1815, Mangas Coloradas took a Mexican captive named Carmen and made her one of his wives. (This young woman turned out to be so willful that some Apaches complained she “didn’t know her place,” a reminder that even captives could improve their situations and assert power.) During the 1820s and 1830s, as Mexico pared down its rationing system and reduced the number of soldiers posted in Sonora and Chihuahua, many Apaches left their communities around the Mexican presidios. After more than a generation of relative peace, many Chiricahuas were still eager to reach an accommodation with the Mexican government. But many others became restless and quite receptive to war leaders such as Mangas Coloradas. By the 1840s, this impressive individual had emerged as the preeminent leader of the war faction among all the Chiricahua bands.

25

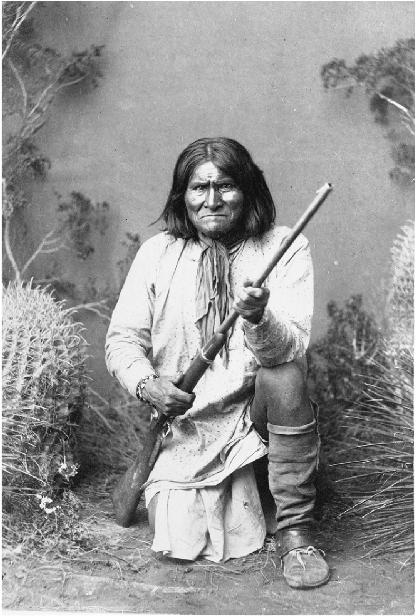

This is the image most Americans have of Geronimo: a determined-looking man clutching a Winchester rifle, with one knee planted on the ground to steady his aim. In the United States, Geronimo is widely remembered as a tragic hero, fighting to preserve his homeland from westward-moving whites. Yet Americans did not take notice of him until he was in his fifties. By then he had spent a lifetime straddling the U.S.-Mexico border engaged in raids and counterraids, taking Mexican captives while seeing members of his family being killed or impressed by Mexican soldiers.

Geronimo came of age hearing stories of Mangas Coloradas and quite possibly training under his supervision. (Adolescents sometimes accompanied raiding parties but were limited to observing the campaign from a distance.) His apprenticeship finally ended in 1846, as Mexico and the United States teetered on the brink of war. As Geronimo later recalled, “Then I was very happy for I could go wherever I wanted and do whatever I liked. I had not been under the control of any individual, but the custom of our tribe prohibited me from sharing the glories of the warpath until the council admitted me.” Geronimo also had another incentive. For some time, he had wished to marry Alope, the daughter of a Bedonkohe man named No-po-so, but No-po-so was not favorably disposed toward him. When the young man asked for Alope’s hand, No-po-so demanded many ponies. “I made no reply,” Geronimo recalled, “but in a few days appeared before his wigwam with the herd of ponies and took with me Alope.” The “days” must have been weeks, during which Geronimo gathered the required animals from Mexican ranches and towns.

26

The couple’s early life coincided with a great increase in the number of Chiricahua raids into Mexico. At the conclusion of the United States’ war with Mexico in 1848, the international border was redrawn, and the Chiricahuas ended up on the American side. They could now raid Mexico, then retreat across the border, where Mexican troops could not follow. Officials in both countries recognized the seriousness of this problem. According to article 11 of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, which officially ended the war, “Considering that a great part of the territory is now occupied by savage tribes, and whose incursions within the territory of Mexico would be prejudicial in the extreme, it is solemnly agreed that all such incursions shall be forcibly restrained by the Government of the United States whensoever this may be necessary.” If policing a two-thousand-mile border today is difficult, it was utterly impossible at a time when there were no fences, passports, or other impediments to the people’s movements. The Chiricahuas, headed by an extraordinary cadre of leaders, continued to launch raid after raid into Mexico. Among their leaders were Mangas Coloradas, who even at sixty years of age remained a formidable presence on the battlefield; Cochise, whose reputation for courage was unsurpassed among the Apaches; Miguel Narbona, who as a boy had been kept for a decade in Mexico as a servant and whose seething resentment toward his former captors made him a formidable foe; Juh, a cousin of Geronimo’s who had a speech impediment but was able to lead his warriors by using hand signals; and Geronimo himself, who showed great promise from an early age. During this

period of active raiding, both Apaches and Mexicans took captives, frequently using them as chips to bring the other side to the bargaining table or to retrieve prisoners.

27

One of the Chiricahuas’ raids changed Geronimo’s life forever. At the start of 1851, the Chiricahuas launched two simultaneous campaigns into the Mexican state of Sonora. One was headed by Mangas Coloradas and included Cochise, Miguel Narbona, Juh, Geronimo, and about 150 battle-tested men. This formidable party made its way almost to the outskirts of the capital city of Hermosillo. The other Apache force was similar in size and kept to the west of the first, targeting the mountain communities and ranches of the Sahuaripa district in the Sierra Madre Occidental. The two parties met less resistance than anticipated. The people of Sonora seemed overwhelmed and even paralyzed by the simultaneous raids. The group of Mangas Coloradas and Geronimo succeeded in rounding up around three hundred head of stock and no less than one thousand horses. But on January 20, a Mexican patrol spotted a large cloud of dust produced by the returning Indians just to the south of a place called Pozo Hediondo (Stinky Well). The soldiers dutifully moved into position and set up an ambush. The battle that ensued started with bullets and arrows but soon devolved into hand-to-hand combat. Mangas Coloradas, never given to exaggeration, called it “a war to the knife.” In the part of the field where Geronimo fought, he was the only man left alive. The Mexican losses were unprecedented. Out of one hundred men, twenty-six were killed—including most of the officers—and forty-six sustained serious wounds. A mere fifteen were left unscathed. It was the most crushing Apache victory over Mexican troops in history.

28