The Other Slavery (37 page)

Authors: Andrés Reséndez

For Geronimo, however, this great victory was a prelude to tragedy. One month after the showdown, Mangas Coloradas, Geronimo, and the other leaders caught everyone by surprise by riding into the presidio of Janos in the neighboring state of Chihuahua. The Apaches were there to sound out the local authorities before opening peace negotiations with Sonora. But their visit also had a commercial purpose. The victorious Apaches needed to dispose of their plunder, and the merchants of Janos had long made their living by acquiring and reselling Indian loot.

One of the Apaches, named Tapilá, began shopping around a saddle that had belonged to the Sonoran captain killed at Pozo Hediondo. His successor as military commander of Sonora, Colonel José María Carrasco, exploded with rage on hearing that these Apaches, who had killed so many Mexicans, had been warmly received at the presidio. On impulse, Colonel Carrasco gathered his men and crossed into Chihuahua without informing anyone. His forces descended on Janos and encircled the nearby Apache encampment, where Geronimo’s family was still bartering. The Apache men were absent from the camp at the time of the attack. Only when they began to gather at nightfall, in the thicket of a nearby river, did they realize the full extent of their losses. As Geronimo put it, “I found that my aged mother, my young wife, and my three small children were among the slain.” He had lost everything that day. “I silently turned away and stood by the river,” Geronimo went on. “How long I stood there, I do not know. But when I saw the warriors arranging for a council I took my place.”

29

For the rest of his life, Geronimo harbored a great hatred for Mexicans. As he said, “My feelings toward the Mexicans did not change . . . I never ceased to plan for their punishment.” And to a remarkable extent, he was able to exact his revenge. His raids are the stuff of legend. “We never chained prisoners or kept them in confinement, but they seldom got away,” he remembered. “Mexican men when captured were compelled to cut wood and herd horses. Mexican women and children were treated as our own people.” Reflecting on the arc of his life in 1905–1906, when he was over eighty years of age, he said, “I am old now and shall never go on the warpath again, but if I were young, and followed the warpath, it would lead into Old Mexico.”

30

The Rising Tide of Servitude

Comanche and Apache raids ravaged northern Mexico in the middle decades of the nineteenth century, resulting in hundreds of captives being taken, but the expansion of the other slavery went far deeper than that. After independence, Mexico extended citizenship rights to all

Indians residing there and abolished slavery. In the absence of slavery, the only way for Mexicans to bind workers to their properties and businesses was by extending credit to them. As a result, debt peonage proliferated throughout Mexico (and in the American Southwest after slavery was abolished there in the 1860s) and emerged as the principal mechanism of the other slavery (see

appendix 6

).

The trappings of debt peonage were in place in Mexico as early as 1587, when an Indian from Michoacán recounted how some Spaniards had advanced him money “at a far higher price than it was worth and then seized my possessions and took me and my wife and children, and they have kept us locked up for twelve years, moving us from one textile factory to another.” The Indian did not know the amount he still owed or how much money he and his family had earned during their twelve years of forced servitude. But he was certain that peonage was worse than slavery because unlike the Africans with whom he toiled, he was not allowed to wander the streets freely even on Sundays. Over the centuries, debt peonage spread. As the Spanish crown abolished Indian slavery in 1542, prohibited the granting of new encomiendas in 1673, and phased out repartimientos after 1777, debt peonage gained ground.

31

After Mexico declared its independence from Spain, the process gained momentum. States throughout the country enacted servitude and vagrancy laws. The state of Yucatán, for example, regulated the movement of servants through a certificate system. No servant could abandon his master without having fulfilled the terms of his contract and could not be hired by another employer without first presenting a certificate showing that he owed “absolutely nothing” to his previous employer. In Chiapas the state legislature introduced a servitude code in 1827 allowing owners to retain their workers by force if necessary until they had fulfilled the terms of their contracts. Lashes, lockdowns, and shackles were commonly used. The same was true in Coahuila. In 1851 the state legislature there allowed owners to flog their peons. Interestingly, the governor opposed the measure because it would affect more than one-third of all the people of Coahuila, according to his calculations. Peonage in neighboring Nuevo León may have been just as common and was especially galling because it was customary to

transfer debts from fathers to sons, thus perpetuating a system of inherited bondage. In these ways, servitude for the liquidation of debts spread all over Mexico. Although Mexico’s faltering economy kept the demand for workers in check in the early decades after independence, once economic growth resumed later in the century, employers went to great lengths to procure and retain coerced laborers.

32

A muckraking American journalist named John Kenneth Turner had unique access to this expanding world of servitude and provided the most detailed portrait of its workings. Posing as a millionaire investor, Turner traveled to Yucatán in 1908. He made his way to Mérida, a town that boasted extravagant mansions and was surrounded by about 150 henequen haciendas. The planters there received the American warmly. These “little Rockefellers,” as Turner called them, had grown rich by selling rope and twine made from the henequen plant. In the early years of the century, Yucatán’s total exports of henequen had reached nearly 250 million pounds a year. But a panic in 1907 had cut severely into their profits, “so they needed ready cash, and they were willing to take it from anyone who came,” Turner explained. “Hence my imaginary money was the open sesame to their club, and to their farms.”

33

Turner’s disguise as a prospective investor also allowed him to ask freely about how workers were hired. “Slavery is against the law; we do not call it slavery,” the planters told him again and again. They generally referred to the Mayas, Yaquis, and even Koreans working at their haciendas as “people” or “laborers,” never as slaves. The “henequen kings” were quite forthcoming about how debt served as a tool of coercion. “We do not consider that we own our laborers; we consider they are in debt to us,” the president of the Agricultural Chamber of Yucatán told Turner. “And we do not consider that we buy and sell them; we consider that we transfer the debt, and the man goes with the debt.” In spite of this verbal obfuscation, the fact was that an Indian worker could be acquired for $400 (400 pesos) in Yucatán. “If you buy now, you buy at a very good time,” Turner was told. “The panic has put the price down. One year ago the price of each man was $1,000.” Obviously, the reason the going rate was uniform was not that all peons were equally in debt, but that there was a market for them irrespective of their debt. “We

don’t keep much account of the debt,” clarified one planter, “because it doesn’t matter after you’ve got possession of the man.” After paying the price, Turner was told, he would get the worker along with a photograph and identification papers. “And if your man runs away,” another planter added reassuringly, “the papers are all the authorities require for you to get him back again.”

34

Turner asked candidly about how to treat his workers. “It is necessary to whip them—oh, yes, very necessary,” opined Felipe G. Canton, secretary of the Agricultural Chamber, “for there is no other way to make them do what you wish. What other means is there of enforcing the discipline of the farm? If we did not whip them they would do nothing.” The American journalist witnessed a formal beating, with all the workers assembled, during one of his hacienda visits. The young man received fifteen lashes across his back with a heavy, wet rope. All henequen plantations had

capataces,

or foremen, who carried canes to prod and whack the Indians. Turner wrote, “I do not remember visiting a single field in which I did not see some of this punching and prodding and whacking going on.”

35

Slavery in Mexico in the twentieth century? “Yes, I found it,” wrote Turner in his extraordinary exposé, published on the eve of the Mexican Revolution. “I found it first in Yucatan.” According to him, the slave population of Yucatán consisted of 8,000 Yaqui Indians forcibly transported from Sonora; 3,000 Koreans, who had departed from the port of Inchon and were on four- or five-year labor contracts; and between 100,000 and 125,000 Mayas, “who formerly owned the lands that the henequen kings now own.” Turner estimated that in all of Mexico, there may have been 750,000 slaves, a figure that is almost certainly exaggerated but that underscores the expansion of the other slavery during the last few decades of the nineteenth century.

36

10

Americans and the Other Slavery

A

MERICANS POURED INTO

the West during the first half of the nineteenth century. In 1800 they occupied a band of settlements along the Atlantic coast that reached from western New York and upper Ohio south along the Ohio River, then through central Tennessee and the Cherokee lands into southern and coastal Georgia. Fifty years later, they were spilling across the plains of Michigan, the hills of Wisconsin, and into eastern Iowa, Missouri, and Arkansas. They were also washing over the Gulf coast from Florida west to Texas and, after the discovery of gold in the late 1840s, all the way to California and Oregon. Larger than any country in western Europe, this area recently opened to settlement became home to about ten million Americans who represented an astounding forty-four percent of the total U.S. population in 1850.

1

Not only were these pioneers experiencing the novelty of the region, but they were also embarking on a journey of self-discovery and reexamination of their beliefs about human relations. Accustomed to African slavery, they were now confronted by the existence of Indian slavery. Variations of the same story unfolded in many quarters of the West: easterners went from surprise to curiosity and, depending on their temperament and persuasion, either acceptance or outrage.

Into New Mexico

The best evidence of these reactions comes from letters and diaries of westbound settlers. James S. Calhoun had never set foot in New Mexico when he was appointed Indian agent for that territory in April 1849. He had grown up in the South, where he had divided his time between managing a shipping firm based in Columbus, Georgia, and pursuing a successful career in state politics. Sensibly, before taking up his post, he traveled to Washington, D.C., to gather information. But as the commissioner of Indian affairs warned him, “So little is known here of the condition and situation of the Indians in that region, that the Department relies on you to furnish it with such statistical and other information.” All the agent could find was a memorandum listing New Mexico’s principal Indian nations: Apaches, “an indolent and cowardly people”; Utes, “a hardy, warlike people subsisting by the chase”; Navajos, “an industrious, intelligent, and warlike tribe”; Comanches, “a numerous and warlike people,” and so on. The document estimated that there were thirty-seven thousand Indians (excluding Pueblos) in New Mexico, a figure that already gave Calhoun a sense of the enormity of the task at hand.

2

Yet nothing could have prepared this Georgian for what he found on the ground. Along the way to Santa Fe, Calhoun heard rumors about Native hostilities against Americans that made him apprehensive. He even offered to raise a regiment of volunteers on behalf of the federal government to provide protection. Once he was in Santa Fe, his concerns only increased. He reported that Indian relations in New Mexico were “of a much more formidable character than had been anticipated” and feared that the number of U.S. troops—six hundred infantrymen in total—was utterly insufficient to control the Indians. This was still speculation.

3

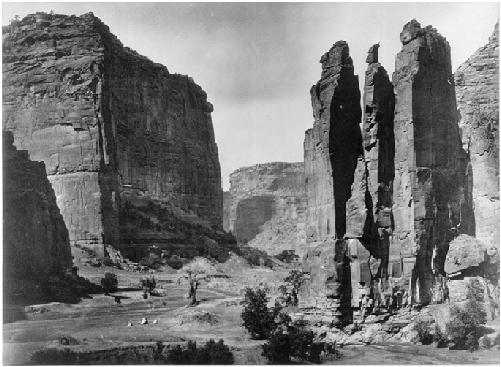

Calhoun’s first tangible experience occurred one month after his arrival, when he joined an expedition to “the seat of the supreme power of the Navajo tribe of Indians,” the famous Canyon de Chelly of Arizona. It was a daring undertaking. For three years, the Navajos had been stepping up their raids on New Mexico’s settlements. To put an end to these attacks and force the Navajos into signing a peace treaty, the territorial

governor decided to visit the Navajo stronghold, accompanied by a detachment of soldiers and the recently arrived Calhoun. From Santa Fe, the party traveled due west through the wide-open, parti-colored plains. After a week of slow progress and difficult conditions, which included camping in places with no water, wood, or grass, they finally reached the gigantic fan-shaped gash in the earth that is the Canyon de Chelly.