The Oxford History of World Cinema (61 page)

Read The Oxford History of World Cinema Online

Authors: Geoffrey Nowell-Smith

the early planning stages with Murnau, 'Film-Dichter' Carl Mayer, and cinematographer

Karl Freund, Together they created the concept of the camera unbound' (entfesselte

Kamera) and cinematic mixture of actors, lighting, and décor that is typical of these films.

Léon Barsacq ( 1976) writes: 'The sets are reduced to the essential, sometimes to a ceiling

and a mirror. In his initial sketches Herlth, influenced by Murnau, began by roughing in

characters as they were positioned in a particular scene; then the volume of the set seemed

to create itself. Thus interiors became simpler and simpler, barer and barer, Despite the

simplification, all the tricks of set design and camera movements were utilized, and some

times invented, for this film [ The Last Laugh]. Scale models on top of actual buildings

made it possible to give a vertigionous height to the façade of the Grand Hotel.'

Towards the end of the silent period Herlth and Röhrig joined forces for one of Ufa's best

films, Joe May's Asphalt ( 1928). They built a Berlin street crossing complete with shops,

cars, and buses, using the former Zeppelin hangar-turned-film-studio at Staaken. After the

introduction of sound they stayed with the Pommer team at Ufa, working with some of

his young talents such as Robert Siodmak and Anatole Litvak and also creating the lavish

period sets for the opulent and very successful multilingual versions of operettas such as

Erik Charell's Der Kongress tanzt ( 1931) and Ludwig Berger's Walzerkreig ( 1933).In

1929 they started a collaboration with the director Gustav Ucicky which afforded them a

smooth transition into the Ufa of the Nazi period. Ucicky, a former cinematographer and

reliable craftsman, specialized in entertainment with a nationalistic touch, and Herlth and

Röhrig were able to avoid the hard propaganda films by working on popular

entertainment. In 1935 they designed the Greek temples for Reinhold Schünzel's satirical

comedy Amphitryon ( 1935), which mocked the pseudo-classical architecture of Albert

Speer's Nazi buildings. Michael Esser describes their concept: 'Set design doesn't create

copies of real buildings; it brings found details into a new context. Their relation to the

originals is a distancing one, often even an ironic one.'In 1935 Herlth and Röhrig wrote,

designed, and directed the fairy-tale Hans im Glück. Shortly afterwards the collaboration

ended.After constructing the technical buildings for Leni Riefenstahl's Olympia ( 1938).

Herlth (whose wife was Jewish) worked for Tobis, then Terra, designing mainly

entertainment films. His first production in colour was Bolvary's operetta Die Fledermaus,

which was shot in winter 1944-5 and released after the was by DEFA.After the war Herlth

first worked as stage designer for theatres in Berlin. In 1947 he designed the ruins of a

Grand Hotel for Harald Braun's Zwischen gestern und morgen ( 1947). Throughout the

1950s he was again mainly involved with entertainment films made by the better directors

of the period such as Rolf Hansen and Kurt Hoffman. For one of his last big productions,

Alfred Weidenmann's two-part adaptation of Thomas Mann's Die Buddenbrooks ( 1959)

(designed in collaboration with his younger brother Kurt Herlth and Arno Richter) Robert

Herlth was awarded a 'Deutscher Filmpreis'.HANS-MICHAEL BOCKSELECT

FILMOGRAPHY Der Schatz ( 1923); The Last Laugh (Der letzte Mann) ( 1924); Tartüff

( 1925); Faust ( 1926); Asphalt ( 1928); The Congress Dances (Der Kongress tanzt)

( 1931); Amphitryon ( 1935); Hans im glück ( 1936); Olympia ( 1938); Kleider machen

Leute ( 1940); Die Fledermaus ( 1945); Die Buddenbrooks ( 1959)

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Barsacq, Léon ( 1976), Caligari's Cabinet and Other Grand Illusions.

Herlth, Robert ( 1979), 'Dreharben mit Murnau'.

Längsfeld, Wolfgang (ed.) ( 1965), Filmarchitektur Robert Herlth.

The Scandinavian Style

PAOLO CHERCHI USAI

For a brief period after 1910, the countries of Scandinavia, despite their low population

(less than 2.5 million in Denmark in 1901; around 5 million in Sweden in 1900) and their

marginal place in the western economic system, played a major role in the early evolution

of cinema, both as an art and as an industry. Their influence was concentrated into two

phases: the first centred on Denmark in the four-year period 1910-13, which saw the

international success of the production company Nordisk Film Kompagni; and the second

on Sweden between 1917 and 1923. And, far from consisting of an isolated blossoming of

local culture, Scandinavian silent cinema was extensively integrated into a wider

European context. For at least ten years the aesthetic identity of Danish and Swedish films

was intimately related to that of Russian and German cinema, each evolving in symbiotic

relation to the others, linked by complementary distribution strategies and exchanges of

directors and technical expertise. Within this network of co-operation only a marginal role

was played by the other northern European nations. Finland, which did have a

linguistically independent cinema, remained largely an adjunct of tsarist Russia until

1917. Iceland -- part of Denmark until 1918 -- only saw its first film theatre opened in

1906, by the future director Alfred Lind. And Norway produced only seventeen fiction

titles, from its first film Fiskerlivets farer: et drama på havet ('The perils of fishing: a

drama of the sea', 1908) until 1918.

ORIGINS

The first display of moving pictures in Scandinavia took place in Norway on 6 April 1896

at the Variété Club in Oslo (or Christiania as it was then called) and was organized by two

pioneers of German cinema, the brothers Max and Emil Skladanowsky. Such was the

success of their show, and of their Bioskop projection equipment, that they stayed on until

5 May. In Denmark, the earliest documented moving picture show was put on by the

painter Vilhelm. Pacht, who installed a Lumière Cinématographe in the wooden pavilion

of the Raadhusplasen in Copenhagen on 7 June 1896. The equipment and the pavilion

were both destroyed in a fire started by a recently sacked electrician out for revenge, but

the show was relaunched on 30 June to a fanfare of publicity. Even the royal family had

visited Pacht's Kinopticon on 11 June.

The arrival of cinema in Finland followed a few weeks on from its first appearance in St

Petersburg on 16 May. Although the Lumière Cinématographe remained in the Helsinki

town hall for only eight days after opening on 28 June, owing to the high prices of seats

and the relatively small size of the city, the photographer Karl Emil Stählberg was

inspired to take action. He took on the distribution of Lumière films from January 1897,

and outside Helsinki the 'living pictures' were made available through the exhibitor Oskar

Alonen. In 1904, Stählberg set up in Helsinki the first permanent cinema in Finland, the

Maailman YmpÁri ('Around the world'). In the same year were produced the first 'real-

life' sequences, but it is not clear whether or not StÁhlberg was also responsible for these.

On 28 June 1896 the Industrial Exhibition at the Summer Palace in Malmö hosted the first

projection in Sweden, again with Lumière material, organized by the Danish showman

Harald Limkilde. The Cinématographe spread north a few weeks afterwards, when a

correspondent of the Parisian daily Le Soir, Charles Marcel, presented films with the

Edison Kinetoscope on 21 July at the Victoria Theatre, Stockholm, in the Glace Palace of

the Djurgärten. They were not a great success, however, and the Edison films were soon

supplanted by the Skladanowsky brothers, who shot some sequences at Djurgärten itself:

these were the first moving pictures to be shot in Sweden.

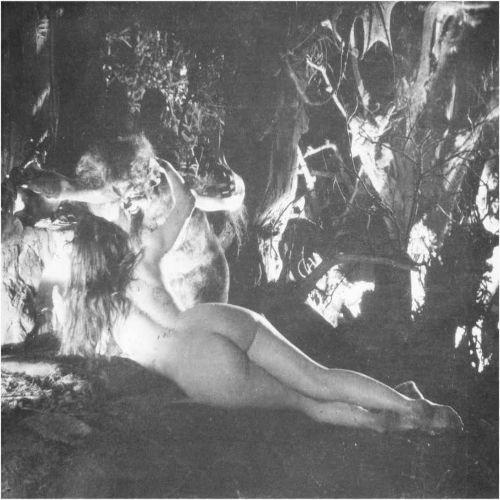

A scene from Häxan (Witchcraft through the Ages), made in Sweden in 1921 by the

Danish director Benjamin Christensen

FINLAND

The first Finnish film company, Pohjola, began distributing films in 1899 under the

direction of a circus impresario, J. A. W. Grönroos. The first location officially designated

for the projection of films was the Kinematograf International, opened at the end of 1901.

But, like the two other cinemas which opened shortly afterwards, it survived for only a

few weeks, and it was not until Karl Emil Stählberg's initiative in 1904 that film theatres

were definitively established on a permanent basis. In 1911 there were 17 cinemas in

Helsinki, and 81 in the rest of the country. By 1921, the figures had risen to 20 and 118

respectively.

The first Finnish fiction film, Salaviinanpolttajat ('Bootleggers'), was directed in 1907 by

the Swede Louis Sparre assisted by Teuvo Puro, an actor with Finland's National Theatre,

for the production company Atelier Apollo, run by Stählberg. In the following ten years,

Finland produced another 27 fiction films and 312 documentary shorts, as well as two

publicity films. Stählberg's near monopoly on production -- between 1906 and 1913 he

distributed 110 shorts, around half the entire national production -- was short-lived.

Already in 1907 the Swede David Fernander and the Norwegian Rasmus Hallseth had

founded the Pohjoismaiden Biografi Komppania, which produced forty-seven shorts in

little more than a decade. The Swedish cameraman on Salaviinanpolttajat, Frans

Engström, split with Stählberg and set up -- with little success -his own production

company with the two protagonists of the film, Teuvo Puro and Teppo Raikas. An extant

fragment of Sylvi ( 1913), directed by Puro, constitutes the earliest example of Finnish

fiction film preserved today. Greater success awaited Erik Estlander, who founded

Finlandia Filmi (forty-nine films between 1912 and 1916, including some shorts shot in

the extreme north of the country), and the most important figure of the time, Hjalmar V.

Pohjanheimo, who from 1910 onwards began to acquire several film halls, and soon

turned to production. The films distributed by Pohjanheimo under the aegis of Lyyra

Filmi were documentaries ( 1911), newsreels (from 1914), and comic and dramatic

narratives, made with the help of his sons Adolf, Hilarius, Asser, and Berger, and the

theatrical director Kaarle Halme.

The First World War brought the intervention of the Russian authorities, who in 1916

banned all cinematographic activity. The ban lapsed after the Revolution of February

1917 and was definitively removed in December when Finland declared its independence.

The post-war period was dominated by a production company founded by Puro and the

actor Erkki Karu, Suomi Filmi. Its first important feature-length film was Anna-Liisa

( Teuvo Puro and Jussi Snellman, 1922), taken from a work by Minna Canth and

influenced by Tolstoy's The Power of Darkness ( 1886): a young girl who has killed her

child is overwhelmed by remorse and confesses to expiate her crime. The actor Konrad

Tallroth, who had already been active in Finland before the war but had then emigrated to

Sweden following the banning of the film Eräs elämän murhenäytelmä ('The tragedy of a

life'), was taken on in 1922 by Suomi for Rakkauden kaikkivalta -- Amor Omnia ('Love

conquers all'), an uneven and isolated attempt to adapt Finnish cinema to the mainstream

features emerging from western Europe and the United States. Production in the

following years was limited in quantity, and tended to return to traditional themes of

everyday life, in the line of contemporary Swedish narrative and stylistic models. Judging

by accounts written at the time, only the documentary Finlandia (Erkki Karu and Eero

Leväluoma/ Suomi Filmi, 1922) achieved a certain success abroad. Around eighty silent

feature films were produced in Finland up to 1933. About forty fiction films, including

shorts, are conserved at the Suomen Elokuva-Arkisto in Helsinki.

NORWAY

The first Norwegian film company of any significance was Christiania Film Co. A/S, set

up in 1916. Before then, national production-represented by Norsk Kinematograf A/S,

Internationalt Film Kompagni A/S, Nora Film Co. A/S, and Gladtvet Film -- had been in

an embryonic stage. Fewer than ten fiction films had been produced between 1908 and

1913, and no record exists of important productions for the two following years.

For the entire period of silent cinema, Norway boasted no studio to speak of, and thus the

affirmation of a 'national style' particular to it derived in large part from the exploitation