The Parthenon Enigma (42 page)

Read The Parthenon Enigma Online

Authors: Joan Breton Connelly

When defeated, the Athenians picked themselves up and remembered. In victory, they remembered too. The precious panoplies of armor and weapons were stripped from the fallen enemy and collected in Greek sanctuaries, giving tangible proof of triumph. The dedication of war booty served several purposes, chiefly that of giving thanks as well as pleasure to the gods who made victory possible. But it also

inspired and indoctrinated future generations of warriors who visited the shrines, educating the young and reminding the broader citizenry of a shared military history.

In this chapter, we shall look at how the imperative of memorializing the heroic dead shaped sacred space, furnishing another mystic cord of memory whereby the Athenians were bound to their remote past.

As with

genealogy, this bond connected the present-day populace not only to one another but also to their legendary forebears and to divinities. It also amplified the emotional and psychic charge of such places, beyond even the effect of their sanctification to particular gods, creating a unique nexus of death, memory, and holiness, of which the Parthenon is the most sublime example.

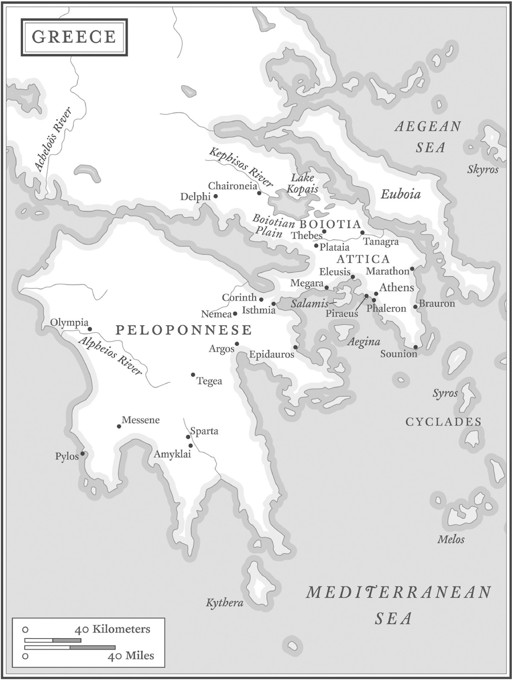

Map of Greece. (illustration credit

ill.84

)

The pattern is attested throughout Greece. Mythic heroes from the

Bronze Age whose “tombs” were still visible in historical times and heroes from the present who died defending their communities: both groups were commemorated within the great sanctuaries. War, death, and remembrance overhung each city, informing the placement of local shrines and the development of local rituals. We will consider as particular examples the great Panhellenic sanctuaries of

Olympia, Delphi,

Isthmia, and

Nemea (facing page), where the tombs of mythical heroes are located close to the

temples of

Olympian gods. Ultimately, of course, our purpose is to understand how the

meaning of the Acropolis’s most sacred spaces developed from the perceived presence of the tombs of Erechtheus and his daughters within temples of Athena: the

Erechtheion and the Parthenon. In this way we can understand how the Parthenon inevitably also became the Athenians’ (and, eventually, all Greeks’) supreme place of memory.

STUDENTS OF ANCIENT GREECE

have long been taught to study space hallowed to gods (and votive offerings left there) as distinct from funerary space (and grave goods), but the two are more interconnected than such thinking allows. Not so surprisingly perhaps: triumph in battle required a combination of human and divine will; the favor and intervention of the gods were absolutely essential but so too was the shedding of human blood. Gods and goddesses must do their part, handing out good fortune and distributing defeat; heroes must give their lives, in return for which their remains are, fittingly, sanctified.

Tombs and temples are thus intricately linked, much like the asking and thanking that characterized Greek piety as a whole. It is no wonder, then, that trophies of war took pride of place within the great sacred precincts. They are the perfect totems of the city’s rightness with the gods.

The great Panhellenic sanctuaries, those that drew Greeks from everywhere across state borders, were dynamic arenas for the display

and commemoration of military victories. Indeed, the development and growth of these sanctuaries were in large part financed by the spoils of war, linking death and worship together from their earliest foundations. At the end of the eighth and the beginning of the seventh centuries, there is a surge in the dedication of arms and armor at sanctuaries and, at the same time, a decline in martial

grave goods deposited in private burials.

26

This has been seen to reflect a shift in emphasis, from honoring an individual’s role as a warrior (marked privately by his family) to commemorating the soldier as national hero, recognized publicly in

rituals financed by the state. This institutionalization of commemoration rites in public sanctuaries has been seen to play an important role in state formation itself.

27

By the early fifth century there were four principal Panhellenic shrines on the official festival circuit of the Greek mainland, known as the

periodos

.

Olympia and

Delphi were the most prestigious, with festivals held in the first and third years of the sequence. Celebrations at Isthmia and

Nemea, both held every second and fourth year of the cycle, were carefully timed so as not to interfere with the more senior festivals.

28

Pilgrims came from all over the Greek world to participate in these feasts; city-states sent their finest athletes to represent them in the associated games. These states contributed to and invested in the Panhellenic shrines, constructing lavish treasury buildings, dedicating expensive offerings, setting up statues of renowned members of their communities, erecting victory monuments, and, very important, offering tithes from the spoils of war, arms and armor from fallen enemies. The local administrations overseeing these Panhellenic sanctuaries not only consented to the setting up of offerings by independent states but absolutely welcomed them as critical investments in their financial, cultural, and religious well-being.

Anthony Snodgrass has shown how sacred pilgrimage to the

periodos

sites made for a world of competitive emulation and cultural exchange in sanctuary centers where information and ideas could be shared by travelers from across the Greek world. In early days, this was very much the rarefied milieu of prominent aristocratic families competing with one another; over time, it evolved into a conspicuous showcase for interstate rivalries, even enmities.

29

This is brilliantly communicated in the dedication of vast amounts of armor and weapons that gave these sanctuaries their overwhelmingly martial character. It has been estimated

that more than a hundred thousand helmets had been dedicated at

Olympia by the seventh and sixth centuries

B.C.

30

The

sanctuary of Poseidon at Isthmia was not far behind, with quantities of arms and armor offered throughout the eighth and seventh centuries, soldiers’ booty awarded after successful campaigns. More than two hundred fragmentary helmets and countless

shields have been excavated from within Poseidon’s precinct, where dedications from wars peaked during the mid-sixth and early fifth centuries.

31

The road leading out from the sanctuary to Corinth was lined with helmets, shields, and cuirasses conspicuously set up as a display of Corinthian superiority.

32

Delphi was a most prestigious setting for the dedication of war booty. It housed the world’s most famous oracle and, as the so-called navel of the earth, was visited by throngs of pilgrims from across the ancient world who came to consult the

Pythia about their future. Visibility was supreme at Delphi, and if a state wanted to show off, this was the place to do it. In the mid-sixth century, the rich king

Kroisos of Lydia dedicated a gold shield at the temple of Athena Pronaia just down the road from the Apollo sanctuary.

33

Herodotos tells that some two thousand shields were sent to Delphi following the Phokians’ defeat of the Thessalian cavalry in a conflict a few years before the

Battle of Thermopylai.

34

In 339

B.C.

, the Athenians sent golden shields to be hung on the new temple of Apollo (the old one having burned down in 373). These were inscribed: “The Athenians from the Medes [Persians] and

Thebans when they fought against the Greeks.”

35

This, of course, was terribly insulting to the Thebans, who had collaborated with the Persians some 140 years earlier. The Athenians made absolutely sure that no one would forget this, broadcasting it here in perpetuity, at the very “navel of the earth.” In 279

B.C.

, following their victory over the Gauls at Thermopylai, the Athenians and Aetolians once again hung gold shields upon the architrave of Apollo’s temple.

36

In fact, no city-state dedicated more monuments at Delphi than Athens did, heaping the sanctuary with lavish offerings to keep Athenian supremacy ever on full display.

37

The Athenians built a treasury entirely of Parian marble, decorated with sculptured metopes showing the exploits of their great heroes

Herakles and

Theseus.

Pausanias says the building was financed from the spoils of their victory at Marathon in 490

B.C.

38

We have already noted in

chapter 3

that a victory monument celebrating

Miltiades’s success at Marathon was set up by the Athenians

at Delphi.

Kimon’s father, the hero of the battle, was shown in a bronze portrait statue, flanked by Athena, Apollo, and the legendary kings and heroes of Athens, images created by no less a master than

Pheidias himself. The Athenians also built a marble stoa at Delphi, commemorating their victory over the Persians at the Battle of Mykale in 479. Here they displayed the actual cables used by Xerxes to bind his famous pontoon bridge across the Hellespont, a triumph of engineering that enabled the Persian army to stream into Greece from Asia. As tangible “

objects of memory,” the captured cords bore witness to the

courage with which Athenians reversed their losses of a decade earlier to defeat the Persian foe.

Panhellenic sanctuaries thus served as international stages on which the Greek city-states broadcast their commitment to winning, putting their resolve on display through the dedication of victory monuments and the establishment of rituals honoring those who served.

39

Let us consider how this system worked.

40

Olympia served as the regional cult place for all of Elis (a district in the northwest Peloponnese), as well as a center for interstate activity. As administrators of the sanctuary, the people of Elis financed the building of the temple of Zeus with spoils from their victory over Pisa in 470

B.C.

But when the

Spartans wished to hang a golden shield on the front gable of the temple (prime real estate for showing off their victory over the Athenians at Tanagra in 458/457), the Elian administration was happy to consent. And so the Spartans installed a great gold shield with a

Gorgon’s head (a symbol of Athena and thereby Athens) along with a hurtful inscription: “From the Argives, Athenians, and Ionians.”

41

This was particularly stinging to their Athenian adversaries, who would ever after suffer in seeing their humiliating defeat memorialized at Zeus’s Panhellenic shrine.

Years later, the Messenians and Naupaktians set up their own victory monument somewhat deflating this Spartan trophy. Supported on a tall column to reach the height of the golden shield fixed on the gable, the beautiful marble statue of Nike (

this page

) was offered by the people of Messene and

Naupaktos following the Athenian victory over the Spartans at

Sphakteria in 425. Thus, we see a monumental tit-for-tat. The master sculpture

Paionios’s winged Nike flew right in the face of the Spartan victory dedication from thirty years earlier. Gold and marble may endure, but triumphant advantage is fleeting.

As early as the Archaic period, we find a tradition for setting winged

sphinxes atop tall columns within Greek sanctuaries. The Naxians erected such a sphinx column just beneath the

temple of Apollo at Delphi around 570–560

B.C.

(

this page

). Fragments of similar sphinx columns have been found in the sanctuaries of Apollo on

Delos, Apollo

at Cyrene, and Aphaia on Aegina, as well as on the Athenian Acropolis (where the column probably stood just north of the Old Athena Temple, insert

this page

, bottom).

42

These dedications served as apotropaic devices, the airborne creatures intended to ward off evil forces that might threaten the temple’s beauty. The flying Victory of

Paionios can be seen as a fourth-century iteration of this long tradition of winged creatures set high in the air above sanctuaries, propelled into flight, as it were. With Panhellenic precincts functioning as great arenas for competitive displays of booty and power, the need for protective charms, as well as boastful emblems of victory, was great.

The Spartan surrender at

Sphakteria was a huge triumph for the Athenians and their allies. It is no wonder the Athenian general

Kleon brought 120

shields from the battlefield to Athens for public display.

43

Some were hung in the Painted Stoa within the Agora; one among these, unearthed during excavations in 1936, bears an inscription confirming its provenance: “over the Spartans at Pylos.”

44

Ninety-nine other shields, also from this victory, were apparently carried up the Acropolis for display on the high podium that supports the Athena Nike temple (

this page

).

45