The Parthenon Enigma (44 page)

Read The Parthenon Enigma Online

Authors: Joan Breton Connelly

A writing tablet, a gilt bridle, a lustral basin, an incense burner, a sacrificial knife with ivory sheath, a linen chiton, some fine muslin cloth, boots: these are varied and very personal offerings that filled the shelves and floors and porches of the temple. Its westernmost room, that which the inventory accounts refer to as the

parthenon

, had giant doors, even bigger than those opening onto the eastern cella, and a great treasure trove locked within: seven gilt Persian swords and a gold-plated helmet, three bronze helmets, and many shields, as well as quantities of furniture, including seven couches from Chios and ten from Miletos, stools, and tables (one with inlaid ivory).

67

And then there were those hundreds of pairs of gold earrings, silver and gold bowls, and so many lyres, all dedicated here in the room called the

parthenon

.

THIRTY YEARS AGO

, in a pair of identically titled back-to-back articles, the Assyriologist

Georges Roux and the Greek epigraphist

Jacques Tréheux vigorously debated the big question: “Pourquoi le Parthénon?”

68

Indeed, why is the Parthenon called by this name? Its translation is simple enough: “Place of the Maidens.” But which maidens and why? Roux rejected this meaning out of hand, advancing the opinion that the word refers not to a group of girls but to the virginity of the goddess Athena and that the room called

parthenon

was, in fact, the eastern

cella of the temple, home to Athena’s monumental cult statue. Tréheux vehemently disagreed, arguing that the word

parthenon

demands a plurality of maidens and that the room in question is the westernmost or back chamber of the building (

this page

).

In amplifying this debate, the French duo seized on an enigma that had puzzled experts since the early days of classical archaeology. Already in 1893,

Adolf Furtwängler insisted that

parthenon

be understood in a plural sense, indeed as a cult place for a group of Athenian maidens. He even named the daughters of Erechtheus (or, possibly, the daughters of Kekrops) as the maidens in question.

69

Wilhelm Dörpfeld saw these maidens not as mythical princesses but as historical

ergastinai

, the “worker women” who wove the

peplos for the Panathenaic festival. He suggested that the actual

weaving took place within the rear chamber of the Parthenon.

70

But there were also, in these early days, those who looked to Athena’s virginity as the source of the name of the building and who, like Roux in later years, believed the

parthenon

to be one and the same with the eastern cella of the temple.

71

At the root of this debate are a series of inscribed inventories that record sacred property housed within the Parthenon (facing page). Beginning in 434/433

B.C.

and running until circa 408/407

B.C.

, the inventories of the treasurers of Athens describe offerings held in the

proneos

(the east porch), in the

hekatompedon

(believed to be the eastern cella), and in a place called

parthenon

(most likely the western room of the building).

72

The accounts also speak of the contents of the

opisthodomos

, which has now been identified as the surviving back room of the Old Athena Temple where treasures, and possibly the olive wood statue of Athena, were kept, at least until the

Erechtheion was built (

this page

).

73

The building we call Parthenon today was known by several names in antiquity. In the fifth century it was simply referred to as “the temple,”

ho neos

.

74

According to a late source, the architects who actually worked on the project and wrote a treatise on its construction—

Mnesikles and

Kallikrates—called the building the “Hekatompedos,” or “Hundred-Footer.”

75

This name could have been used in remembrance of what came before it on this same spot. (As discussed in

chapter 2

, something called the Hekatompedon is attested on the

Archaic Acropolis and may have occupied the space where the Parthenon stands today.)

76

But by the fourth century, the word

parthenon

had come to be used for the entire temple.

77

It is

Demosthenes who, in 345/344

B.C.

, gives us our first

attested use of this word to describe the Parthenon as a whole.

78

Interestingly,

Plutarch combines the two names, referring to the building as the “Hekatompedon Parthenon.”

79

And by the time Pausanias writes in the second century

A.D.

, he refers to the temple simply as “the building they call Parthenon.”

80

As Roux and Tréheux point out, there are other sanctuaries besides

that of Athena at Athens that have places called

parthenon

within them. These include the shrines of

Artemis at Brauron, Artemis at Magnesia on the Maeander, and

Meter Plakiane at Kyzikos on the Black Sea.

81

The presence of maidens, and a room for them, at the shrines of the virgin goddess Artemis are easy to understand. Less clear would be why the mother goddess Meter Plakiane would be associated with a

parthenon

.

82

Seizing on the case at Magnesia, Roux points out that Artemis was worshipped here under the epithet Loukophryne and not Parthenos, and uses this to bolster his argument that Athena Polias at Athens could still have a temple called Parthenon.

83

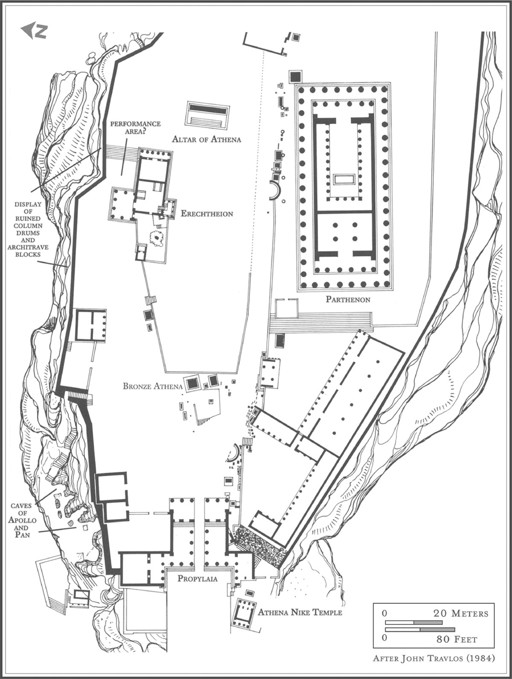

Plan of Acropolis showing classical and Hellenistic monuments. (illustration credit

ill.89

)

Which invites the question: Is “Parthenos” an epithet at all? Indeed, Athena is not worshipped under the name Athena Parthenos at any site outside Athens.

84

But even if it were, it would be highly unusual for a place-name to be formed from an epithet. Normally, place-names are formed from a divinity’s proper name. A place sacred to Hera is called a Heraion. A place sacred to Artemis is an Artemision. A precinct sacred to Athena should be called an Athenaion. A room belonging to a single maiden is a

parthenion

(in Greek script, παρθένιον, with the ending -ιον). A

parthenon

(written παρθενών, with the ending -ων), however, is clearly a place that belongs to a plurality of maidens. Most nouns whose ending is spelled -ων or -εων have a collective sense.

85

Elaion

is therefore a place full of olive trees,

hippon

a place for horses,

andron

is a place for men, and

gynaikon

a place for women.

Our “place of the maidens” could well be explained by Athena’s words at the very end of Euripides’s

Erechtheus

in which she instructs Praxithea to bury her dead daughters in a single earth-tomb and to establish a temenos to them. Athena then orders the queen to build, for her dead husband, a precinct (

sekos

) with stone enclosure in the middle of the Acropolis. Euripides is here offering by etymology an explanation for the foundation of the two great cult buildings on the Periklean Acropolis: if the

Erechtheion incorporates the tomb of Erechtheus, then the Parthenon must incorporate the tomb of the virgins.

Indeed, the westernmost room of the Parthenon could have been perceived to cover the very spot where the tomb of the virgin daughters of Erechtheus lay. This would accord with the Erechtheion, where the tomb of Erechtheus was understood to rest beneath the western part of the building. If this is so, then the heroic father and daughters were more intimately connected to the worship, and cult buildings, of Athena than we have previously imagined. Not only was their sacrifice celebrated on the frieze; together with the goddess herself, they received the most holy and most glorious temple honors, sacrifices, and

ritual devotions.

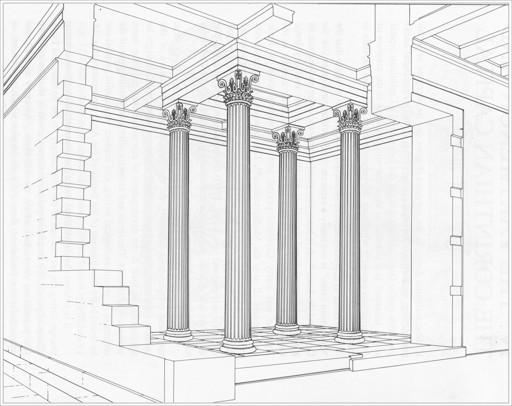

Western room of Parthenon as reconstructed with proto-Corinthian columns. By P. Pedersen. (illustration credit

ill.90

)

While heroes of other Panhellenic sites may have died tragic deaths and received burial within sanctuaries, cult honors, and funerary games, it is at Athens alone that the heroic deaths served a higher purpose. Indeed, only at Athens did the city’s founder-hero and his heroic daughters give their lives to save their entire community and its future. The transcendent selflessness of the Athenian heroines speaks directly to the core values that the citizens of Athens professed as uniquely their own.

The identification of the west room of the Parthenon with the tomb of the Erechtheids is bolstered by evidence for burials of other heroic maidens in proximity to the temples of the goddesses with whom they were closely connected.

Iphigeneia’s tomb was located in the sanctuary of Artemis at Brauron, while the tomb of

the daughters of Antipoinos was set within the sanctuary of Artemis of Glory in

Thebes. Of course, Iphigeneia was sacrificed to resolve a crisis for the collective good of the Greeks; she helped the Greek fleet set sail for the Trojan War. And the daughters of Antipoinos gave their lives in order to save their city of Thebes from attack, just as the Erechtheids did for Athens. All these maidens received heroic burials and sacred rites within the holy precincts of the goddesses they were close to.

86

The westernmost room of the Parthenon, in fact, gives us an important hint of its ambient funerary character (previous page).

Poul Pedersen has persuasively argued that the four interior columns supporting its roof were crowned by a proto-version of

Corinthian capitals.

87

He further relates the layout of this unusual “center-space room” to the cult building of the

Eleusinian Mysteries, the Telesterion at Eleusis, a structure designed by none other than the architect of the Parthenon itself: Iktinos.

88

Vitruvius tells us that the

Corinthian order originated with a basket (

kalathos

) left at the tomb of an aristocratic maiden at Corinth. An

akanthos plant grew up and around the openwork of the basket, giving it a beautiful, leafy appearance that caught the eye of the architect Kallimachos as he passed by. Inspired by this pleasing form, Kallimachos reportedly designed a column capital imitating the shape of the tender leaves entwining the basket: thus, the Corinthian order was born. And as

Joseph Rykwert has demonstrated, Vitruvius’s account contains five telltale elements: a

virgin, a death, an offering basket, akanthos, and the notion of rebirth.

89

As we shall see at the end of this chapter, the daughters of Erechtheus are intimately associated with each of these elements. And it would seem that the deliberate innovation of

proto-Corinthian capitals on the columns in the room called

parthenon

signals the funerary function of this deeply sacred space.

Akanthos leaves take center stage, once again, at the very peak of the Parthenon’s gables, which were crowned by an astonishing pair of giant floral akroteria, one at either end of the temple (insert

this page

, bottom). Carved in Pentelic marble, these show a highly innovative and ambitious openwork design and soar to an astounding height of nearly 4 meters (13 feet). Some twenty-seven fragments of these rooftop anthemia survive, showing fully developed akanthos scrolls and spreading leaves. It is a wonder that this delicate masterpiece of openwork, carved from heavy marble, could have survived production and hoisting into place.

90

Indeed, Pedersen emphasizes the groundbreaking free-plastic manner in which the openwork floral finials have been rendered. He makes a connection between these pioneering akanthos akroteria and

the akanthos leaves of the equally innovative proto-Corinthian capitals he restores in the Parthenon’s westernmost room. Tracing the metamorphosis of traditional lotus-palmette and scroll anthemia seen on Archaic and classical funerary monuments, Pedersen sees a development toward akanthos leaf finials for gravestones of the late fifth and early fourth centuries.

91

Of essential importance to our argument is the relation between the akanthos elements on grave stelai and those atop and within the Parthenon. With four Nikai hovering above the corners of its roof (

this page

) and two akanthos akroteria at the very peak of its gables (insert

this page

, bottom), the Parthenon signals loud and clear that it is at once a monument to

Athenian victory and at the same time a final resting place for the maidens who gave their lives to win Athenian triumph.