The Parthenon Enigma (47 page)

Read The Parthenon Enigma Online

Authors: Joan Breton Connelly

7

THE PANATHENAIA

The Performance of Belonging and the Death of the Maiden

ONLY TEN WOULD BE CHOSEN

. Night after night, nervous boys filed into the ruins of the Theater of Dionysos at the foot of the Acropolis, taking a place center stage. There, each sang his heart out while the odd foreign woman sat among the marble thrones, where eminent Athenians had assembled in ancient times. She fixed her gaze upon each of them, one by one, until she had seen two hundred “ragged urchins.”

Isadora Duncan knew exactly what she was looking for. She would leave Athens with a chorus of ten Athenian boys.

1

Duncan and her family had come to Athens in the autumn of 1903, setting up residence at a place called

Kopanos on the slopes of

Mount Hymettos, a location that afforded them an unobstructed view of the Acropolis. Construction of the family compound, which they called their “temple,” was begun with great ambition but never finished. With typical impetuousness, the family had purchased land lacking an accessible water source. By the end of the year Isadora would have left. But the months spent in Athens were transformative and full. Engaging with poets, singers, dancers, monks, villagers, and royalty, they created their own community, in which they experimented with dance, theater,

music, and weaving. The Duncans recited and danced each morning in the Theater of Dionysos. In the afternoons they scoured the city’s museums and libraries, trying to understand ancient Greek form and movement through a study of poetry, drama, sculpture, and vase painting.

Especially eager to understand the sound of ancient music, Isadora and her brother Raymond, who had met and quickly married

Penelope Sikelianos, sister of the great poet, sought out manuscripts of Byzantine liturgical music. They had a theory that songs of the early Christian Church derived from the

strophes of ancient Greek

hymns. The Duncans also listened carefully to local men and boys singing traditional folk tunes, ever alert for vestiges of classical Greek music.

Isadora was determined to re-create an ancient boys’ chorus to tour with her across Europe in

Aeschylus’s

Suppliants

. Indeed, she collected the best young male voices of Athens, enlisting an Orthodox novice priest with a specialty in Byzantine music to train the ten lucky lads for the ensemble known as the

Greek Choir. Clan Duncan and the singing boys left Athens for Vienna, Munich, and Berlin before the year’s end.

In Munich they performed for students of the great archaeologist

Adolf Furtwängler, who introduced the event with a lecture on the Greek hymns that had been set to music by the novice. The boys, costumed in robes and sandals like an ancient chorus, sang this canon. Isadora herself danced all fifty of the Danaids. The audience was enthralled.

With each new venue, however, enthusiasm for the choir waned. By the time they got to Berlin, six months into the tour, the boys’ voices had started to change, the once mellifluous tones growing ever more shrill and off-key. They had lost that heavenly boyish expression that had so captured Duncan in the Theater of Dionysos. They had also grown in height, some sprouting up by as much as a foot, and in rambunctiousness. By the spring of 1904, they would be sent home to Athens via second-class coach train from Berlin, in their bags the knickerbockers that had been bought for them at Wertheim’s department store, mementos of Duncan’s great experiment re-creating the ancient Greek chorus.

2

Though breathless and flamboyant, Isadora’s pursuit of what she perceived to be ancient sounds and movements remains instructive today. During her time in Athens, Duncan climbed the Acropolis often, summoning the power of the architecture to stir something within herself. Her descriptions of awaiting inspiration are affecting and natural:

For many days no movement came to me. And then one day came the thought: these columns which seem so straight and still are not really straight, each one is curving gently from the base to the height, each one is in flowing movement, never resting, and the movement of each is in harmony with the others. And as I thought this my arms rose slowly toward the Temple and I leaned forward—and then I knew I had found my dance, and it was a Prayer.

3

Duncan had understood, in an instant, the quintessence of movement as prayer. Her epiphany, within the peristyle of the Parthenon,

elicited a gesture that sprang from her diaphragm, forcing her arms upward in a pose of supplication.

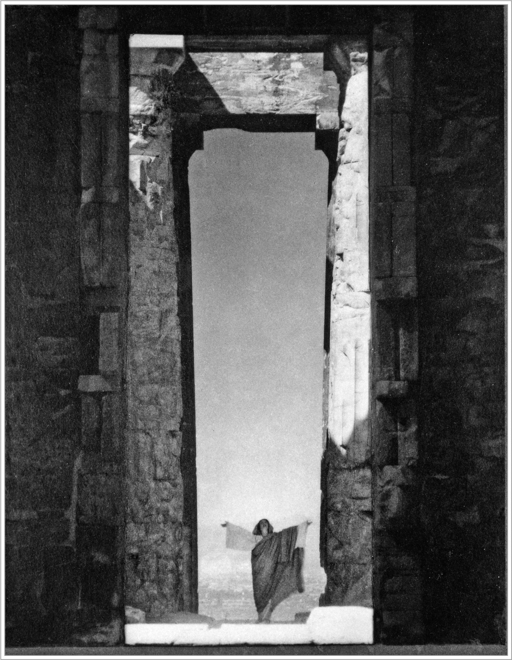

Edward Steichen’s celebrated photographs of Duncan’s striking stances within the Parthenon’s colonnade (previous page) were shot in 1920, seventeen years after she wrote the lines quoted above.

4

Like so many others before and after her, Duncan would feel compelled to revisit the Parthenon throughout her life.

Isadora Duncan in the porch of the Parthenon, photographed by Edward Steichen, 1920. (illustration credit

ill.93

)

Generations of ancient Greeks did the same. In fact, every August for more than 800 years they streamed en masse toward the Acropolis, in a colorful procession that was the climax of the Panathenaic, or “All-Athenian,” festival. Officially founded in the year 566/565

B.C.

, according to tradition, the

Panathenaia was celebrated until the fourth century

A.D.

, when a series of edicts issued by the Christian emperor Theodosios put an end to all “pagan” rites and

festivals, closed Greek temples, and eradicated traditional worship. The final festival was probably held in

A.D.

391 or, at the very latest, in 395.

5

Across the uninterrupted centuries of observance, every fourth year saw an especially grand weeklong version of expanded contests and rites. Known as the Great (or Greater) Panathenaia, this version was international, open to participants and competitors from across the Greek world, whereas the Small (or Lesser) Panathenaia, observed during each of the intervening years, was local, its competitions open to Athenian citizens alone.

6

One naturally thinks of the Olympics by comparison, the quadrennial games open to the whole Greek world (with Panhellenic contests held in the intervening years at

Delphi,

Nemea, and

Isthmia). There are indeed meaningful similarities, not least of which is that the Panathenaia, like the Olympics, was at bottom a religious observance. But while it must be allowed that the Olympic, the Pythian, and other Panhellenic festivals were more important occasions in the Greek world generally (even than the greater version of the Panathenaia), there was no more important occasion in Athens. The Panathenaia comprised the days when the Athenians were most intensely, ecstatically themselves—a crescendo of being and consciousness. At its heart, more important than any of the other

rituals or competitions, was the procession itself. And the destination of that sacred, definitive procession was none other than the sacred

altar of Athena just to the northeast of the Parthenon (insert

this page

, top).

In what can be described as the ultimate multimedia spectacle, the

procession of worshippers was the culmination of both the Great and

the Small Panathenaic festivals. This visual and acoustic marvel began at dawn in the Kerameikos, just outside the city gates at a structure called the

Pompeion, or “Procession Building.” Here, processionists lined up in groups according to their social status, gender, and age cohort. Passing through the Double Gate (Dipylon), they followed the Sacred Way, crossing the Agora and climbing up the Acropolis, where they entered through the monumental gateway (

Propylaia) before marching on toward Athena’s sacred altar (

this page

).

7

In train were a hundred head of cattle for sacrifice to the goddess, an act of collective devotion. Following the sacrifice, the meat was cooked and distributed, a feast shared by all participants, citizens and noncitizens alike.

The Small Panathenaia was, as we have said, a local festival, its competitions open only to citizens from the ten tribes. The Gre

at Panathenaia, including contests open to all Greeks, nevertheless restricted certain competitions to Athenian citizens alone. These so-called tribal events included some of the horse races, the boat race, the torch relay race, and a men’s beauty contest. Also among these was the

pyrrichos

, a competition for armed dancers, and the

apobates

race, which involved contestants jumping on and off a moving chariot wearing full armor. The vigil called the

pannychis

, or “all-nighter,” generally thought to have been held on the eve of the procession, was open only to youths and maidens from citizen families. The following day, as the procession reached the gateway of the Acropolis, only members of these families were allowed to enter Athena’s sacred precinct.

The rites and competitions of the Panathenaia, in substance and exclusivity, enabled Athenian citizens to articulate the very essence of who they were. In no other setting, perhaps not even warfare, would they have so keenly felt the

awareness of being bound together as families and tribes descended from a common point in the epic past. As in Linnaean taxonomy, one could find himself based on membership in a household (

oikos

), a kinship group (

genos

)—known across four generations and associated with the elite—a larger “brotherhood” group (

phratry

), and one of the ten tribes (

phylai

) established by

Kleisthenes in 508/507

B.C.

in the early days of the democracy. This intricate system made the blood bond of Athenian

citizenship essential while exerting enormous pressure against any notion of including outsiders.

8

The prominence of the tribal events at the Panathenaia sets it apart from festival practice at other Panhellenic game sites, those at Olympia,

Delphi, Isthmia, and Nemea. Little if any emphasis was placed on the superiority of the local hosts at these sanctuaries. Indeed, at Athens, administration of the festival was itself very much a tribal affair. Each tribe appointed one representative, drawn by lot, to a board of ten magistrates known as

athlothetai

who oversaw the organization and preparations for the festivities, including the awarding of prizes.

9

They were also responsible for the

financing of the games, a hugely expensive underta

king. The office had a four-year term, providing time enough for officeholders to announce and organize the contests, as well as for them to oversee the

weaving of the sacred peplos for Athena, a job performed by a group of women called

ergastinai

(workers) over nine months.

10

As we understand it from the fragmentary sources, a giant tapestry-peplos was presented to the goddess (from the sixth century on) every four years at the Great Panathenaia, while a small peplos was woven for the Small Panathenaic festivals held during the intervening years.

11

These peplos offerings are understood to have been deposited near the olive wood statue in the Old Athena Temple (or what remained of it) and possibly later in the

Erechtheion, following its construction in the last quarter of the fifth century

B.C.

, though this is by no means certain.

Time was crucial in all matters related to administering the festival. The timing of the events themselves was synchronized with celestial configurations of star groups and

moon phases so that the Panathenaia would be as one with the cosmos.

12

Athenian piety also required that the festival be in harmony with the natural surroundings, the landscape, flora, and fauna of Athens, all the

places of memory that pulsed with the mythic past and kept it alive. But like the rivers and the wind, the observances of the festival were sometimes wildly kinetic, and this is perhaps the hardest element for us to recover.