The Parthenon Enigma (49 page)

Read The Parthenon Enigma Online

Authors: Joan Breton Connelly

The musical events were first performed in the Agora, where temporary stands were erected in an area known as the orchestra. Some believe that the contests were transferred in the 430s to a music hall built by Perikles at the southeast foot of the Acropolis, just beside the

Theater of Dionysos (

this page

).

32

Still, epigraphic evidence attests to the continued use of the Agora for some musical

performances, even after the death

of Perikles.

33

By the last quarter of the fourth century,

Demetrios of Phaleron is believed to have moved the musical and rhapsodic competitions to the Theater of Dionysos.

34

The theater had been entirely rebuilt by

Lykourgos in the 330s, increasing its seating capacity to around seventeen thousand. Lykourgos also built a new Panathenaic stadium entirely of marble, set just beside the Ilissos River (

this page

). The footraces along with most of the gymnastic events were no doubt moved at this time to the lavish new stadium. Venue changes allowed contemporary Athenian leaders to put their own stamps on the competitions, eclipsing the memory, not always pleasant, of former regimes. Setting the Panathenaic competitions became, in this sense, a power play, whereby vast numbers of worshippers could be made aware of the contributions of political leaders to refreshing traditions, even as the universal past was invoked and glorified.

35

The recitation of epic song narratives on the first day of the festival reconnected worshippers with the sentiments and ideals of their ancestors. If there was anything that approached the status of a sacred foundation text for all Greeks, it was Homer’s account of the

Trojan War and its aftermath as told in the

Iliad

and the

Odyssey

. In

Against Leokrates

, Lykourgos emphasizes that the ancestors legislated changes to the Great Panathenaia in order to ensure that Homer’s, and

only

Homer’s, work would be recited at the festival. “Poets,” Lykourgos observes, “depicting life itself, select the noblest actions and so through argument and

demonstration convert men’s hearts.”

36

Lykourgos is referring to what has been called the “

Panathenaic Regulation,” by which the Homeric poems were established as those to be performed, or “reperformed,” at the Panathenaia. This measure has been traced, by some, all the way back to

Solon’s day.

37

Listening to the

Iliad

and the

Odyssey

enabled all participants in the festival, Athenians and non-Athenians alike, to start the week off “on the same page,” reflecting in the proper spirit on their common origins as Hellenes. There would be plenty of time later in the week for the Athenians to show off their superior lineage while the outsiders watched.

A roster of rhapsodes recited the Homeric poems in a relay sequence, one picking up where the other left off, each declaiming five hundred to eight hundred lines. In a sense, this resembled the footraces of the tribal competitions that followed, the sharing of the performed text as a “team event.” Indeed, both the athletic and rhapsodic competitions were referred to as

agones

(contests). And like all Panathenaic contests the rhapsodic, at its core, was a ritual, one in which participants both collaborated and competed, as

Gregory Nagy has emphasized. It is generally believed that the versions of the Homeric poems recited at the Panathenaia were organized, or reorganized, by

Hipparchos, son of

Peisistratos.

38

By the Hellenistic period, theatrical contests were added to the schedule of events, and by Roman times we hear that tragedies were also performed.

39

In the middle of the fifth century, Perikles, by now one of the

athlothetai

overseeing the festival, seems to have put his own stamp on the first day of the festival. Apparently, he had a decree passed introducing a musical contest, personally prescribing every detail of how contestants should blow on the

aulos, sing, or pluck the

kithara.

40

That musical competitions became so integral to the Panathenaic Games signals the centrality of music making (which included rhapsodic recitation) in ancient Athens. It equates this art with athletic contests, placing it under the same umbrella of competition and expenditure of energy for the delight of the goddess, a species of prayer. There is indeed a certain physicality to playing instruments, singing, and reciting poetry that renders the effort akin to athletic exertion. Music, no less than athletics, demands raw talent, rigorous training, and performance skills. For this reason, with memorization of words, athletics, and dance, music was central to the education of the young. That the Panathenaic

competitions tested all the abilities cultivated in Athenian paideia is no accident: this training of the next generation in the values and ideals of the polis was essential to good

citizenship. To be Athenian was to belong, by reason of birth above all but by formation as well.

Music was ubiquitous at the Panathenaia. The sounds of pipes and lyres accompanied athletic contests as well as

animal sacrifices and other rites. Indeed, the shrill tones of the

aulos masked the cries of animal victims as their throats were cut upon the

altar of sacrifice. Music punctuated and articulated the progressive stages of sacrifice. Some sense of the ancient experience may survive in the Spanish bullfight in which a band of musicians accompanies each phase of the spectacle: arrival of the bull, arrival of the torero and banderilleros, entry of the picador on horseback, killing of the bull, awarding of prizes, and exit from the arena. In Athens, musical punctuation also marked stages within athletic competitions, the sound of pipes signaling the start of events and the awarding of prizes.

The musical competitions (

musikes agones

), held on the first day of the festival, were divided into two classes, one for boys and one for men, separating voices that had not yet changed from those that had.

41

They were further subdivided into contests for playing and singing with aulos accompaniment and ones for accompaniment by the

kithara.

42

The English word “guitar” derives from the word kithara denoting the large seven-stringed lyre.

43

The global renown of ancient

kitharodes

who traveled on tour from town to town finds certain parallels in the fame of contemporary rock musicians who sing and play the guitar. In some sense, kithara players were the rock stars of Greek antiquity, and they were comparably compensated, enjoying the patronage of wealthy tyrants and political leaders. At the Panathenaia, the value of their prizes hugely exceeds the awards given in all other contests. First-place

kitharodes

received not an amphora of olive oil but a gold crown worth a thousand drachmas, plus five

hundred drachmas in silver. By comparison,

kitharistai

, those who played the kithara but did not sing, received a crown worth just five hundred drachmas, plus three hundred drachmas in cash. And the

kitharode

competition had second-, third-, fourth-, and even fifth-place finishers, where no other Panathenaic contests did. All musical competition was lucrative but nothing matched the kithara contest. First place in competitions for a combination of singing and playing the pipes (

aulodia

) brought prizes of a wreath and three hundred drachmas in cash. Musicians who played the pipes alone without singing (

auletai

) received only a wreath.

44

Athletic competition, meanwhile, was organized into three leagues: one for boys, one for beardless youths (

ageneioi

), and one for men.

45

These contests started on the second day, with boys competing in six events and youths in five. On the third day, the men’s competitions comprised nine events.

46

Track-and-field contests included running the

stadion

(at Athens, a distance of 185 meters, or 607 feet), the

diaulos

(2 stadia, or 370 meters), the

hippios

(4 stadia), and the

dolichos

(24 stadia). Men also competed in a special two-stadia race that required them to run fully armed, testing the strength and endurance needed on the battlefield.

The

pentathlon events were hugely exciting for viewers, who watched naked athletes compete in a comprehensive and grueling test of their physical strength, stamina, speed, and flexibility. Indeed, competitors had to show real versatility and all-around robustness in running the

stadion

, competing in the long jump, throwing the discus and the javelin, and wrestling.

47

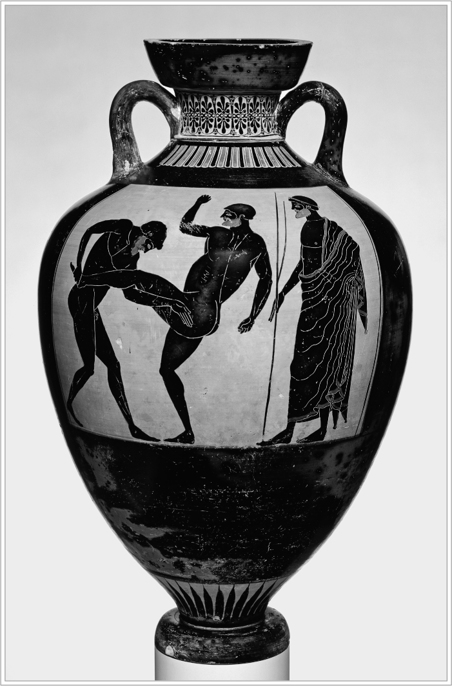

Boxing and the punishing

pankration

, a combination of boxing and wrestling with no holds barred (only eye gouging,

kicking, and biting were forbidden), rounded out the

gymnikoi agones

, literally contests undertaken in the nude. A Panathenaic amphora by the

Kleophrades Painter, dating to the last quarter of the sixth century, captures something of the brutal drama of the

pankration:

a burly nude combatant is twisted into an unwieldy position by his able adversary as a judge watches (previous page).

48

These contests provided thrilling and extreme spectacles for the throngs of Panathenaic viewers. We hear of one acclaimed

pankratiast

from Sikyon,

Sostratos, who in the fashion of modern-day World Wrestling Federation stars, won a nickname for his special prowess: Akrochersites, “the Fingerer” or “Mr. Fingertips.” This was owing to his signature move, in which he entered the ring and immediately broke the fingers of his opponents, putting them at serious disadvantage for the rest of the match. It proved an effective strategy; indeed, “the Fingerer” won three consecutive victories at the Olympics (364, 360, and 356

B.C.

), twelve combined victories at the Nemean and

Isthmian Games, and two at the Pythian Games at Delphi. Though there is no surviving evidence that he competed at Athens, we know he was honored with portrait statues set up at both Olympia and Delphi.

49

Burly athletes competing in the

pankration.

Panathenaic prize amphora, the Kleophrades Painter, ca. 525–500 B.C. (illustration credit

ill.96

)

The fourth day of the Panathenaia was devoted to equestrian events. These were first held in the Agora but, by the fourth century, had been transferred to a hippodrome built at New Phaleron.

50

The equestrian competitions naturally had a certain military aura about them, testing the speed of the horses as well as the agility of riders and drivers, skills critical on the battlefield. There were bareback races, two-horse chariot races (

synoris

) that ran eight laps around the hippodrome, and four-horse chariot races (

tethrippon

) that ran for twelve laps. There were races for Athenians and those for non-Athenians; races run by yearlings and those run by mature horses. As is the practice today, awards went to the owners rather than to the jockeys or charioteers. Indeed, fielding a team of horses was enormously expensive, impossible for all but the wealthiest of the elite.

The fifth day of the games was wholly reserved for contests open to Athenian citizens alone. There was the

pyrrichos

(a dance in full armor), the

apobates

race, an equestrian event called the

anthippasia

, a boat race, the

euandria

(a beauty contest for mature men), and a torch relay race. These tribal contests evoked sacred memories of the earliest ancestors, emphasizing their physical and aesthetic excellence, their strength and agility in battle, and their grace in dance and comportment. Above

all, tribal events stressed military readiness and power; foreign teams and visitors were compelled to watch a celebration of Athenian supremacy designed, at least in part, for their discomfort.

The pyrrhic dance competitions required contestants to dance nude, hold a shield, and imitate movements from combat: dodging, jumping, crouching, striking, hitting, and lunging.

51

There were separate heats for boys, beardless youths, and men. The dance was attributed to Athena herself, who, according to her birth story, sprang from the head of Zeus in full armor and dancing the

pyrrhike

. It was understood to be a dance of joy anticipating her victory in the

Gigantomachy.

52