The Parthenon Enigma (46 page)

Read The Parthenon Enigma Online

Authors: Joan Breton Connelly

The name Hyakinthos is a very ancient one with pre-Greek origins, signaling the great antiquity of cult worship here.

113

But the Hyakinthia festival was probably not introduced until sometime in the eighth century

B.C.

when the sanctuary was formalized.

114

So important was the observation of these sacred rites to Spartans, and especially to the Amyklaioi, that they interrupted warfare each summer so that all could return home to participate in the three-day festival.

115

From what we can tell, it began with a solemn day of mourning and sacrifice, commemorating Apollo’s grief in losing his beloved. In contrast, the second day was one of joy, expressed in a colorful procession along the Sacred Way

from Sparta to Amyklai. There was singing and dancing by maidens,

performances by choruses of boys and adult males, the singing of a paean, and the presentation of a woven chiton to Apollo, all culminating in a celebratory communal banquet.

116

There is obvious overlap between the daughters of Erechtheus and the young hero Hyakinthos; indeed, at the end of the

Erechtheus

, Athena proclaims that the girls will henceforth be called the “Hyakinthian goddesses.”

117

Like Hyakinthos, the maidens die young, are buried beneath the temple of the goddess with whom they are so closely associated, and come to be remembered in cult worship, festival, and contests. But comparison stops here. Unlike Hyakinthos, a victim of

Zephyr’s petty jealousy, the daughters of Erechtheus died for the noblest of causes, saving their city, an act that speaks to the core values that made Athenians different from everyone else.

The best-known story of the dying Hyakinthos is how his blood dripped upon the earth and was transformed into the violet flower we still call hyacinth today.

118

According to one tradition, all three of the daughters of Erechtheus were sacrificed at a place called

Hyakinthos Pagos, “the Purple Rock.”

119

Assimilation of the Spartan myth with the Athenian tale of the Erechtheids may also account for a late tradition in which Hyakinthos was an adult Spartan living at Athens. When a plague threatened the city, an oracle demanded virgin sacrifice to make it stop, and so Hyakinthos offered his daughters to be killed.

120

Thus the mythical and ritual orbits of Athens and Sparta become very much entwined.

Let us conclude our pilgrimage through the Panhellenic

periodos

sites at the very center of Earth. In primordial times at

Delphi, the earth-serpent

Python presided over the cult center of his mother, Ge. Apollo wanted to take Delphi for his own and so slew the mighty Python, burying him deep within a cleft on the slopes of

Mount Parnassos. This is the spot from which oracular vapors rose, sometimes called the

omphalos

, or “navel,” the very center of the earth. It is atop this fissure and the burial place of Python that Apollo’s temple came to be built. Thus we find, once again, a “tomb” beneath a temple. Python gives his name to the

Pythia, the priestess who sat above the cleft on a tripod within Apollo’s temple, pronouncing oracles. Python also gives his name to the Panhellenic festival the Pythaia and athletic competitions known as the Pythian Games. Thus, the serpent is forever commemorated within Apollo’s sacred precinct.

121

A second monumental death occurred within the sanctuary at Delphi, one that was commemorated with a tomb, shrine, festival, and sacrifices. Neoptolemos, son of

Achilles, was killed by a priest in the doorway of Apollo’s temple.

122

We are told that his body was first buried on the spot where he was killed, that is, beneath the temple’s threshold.

King Menelaos later moved it a short distance away.

123

Strabo speaks of Neoptolemos’s grave, and Pausanias claims to have seen it, just to the left, or north, as one exits the temple of Apollo.

124

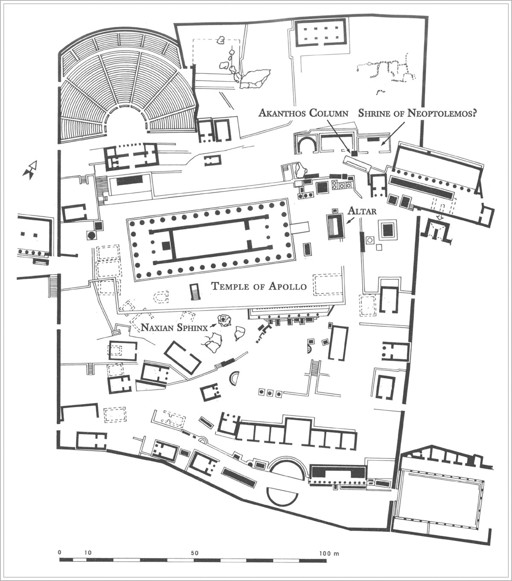

Foundations for a small building unearthed on this spot have been identified as belonging to the hero shrine of Neoptolemos, though this is not certain (above).

125

Location of Shrine of Neoptolemos and the Akanthos Column set just beside it, sanctuary of Apollo, Delphi. (illustration credit

ill.91

)

Still, the importance of Neoptolemos at Delphi is of paramount interest. In Homeric epic, the young warrior takes center stage in a number of grisly episodes. On the night of the fall of Troy, Neoptolemos savagely beats King Priam to death, using the body of

Astyanax, the king’s own little grandson, as a club. The fact that this murder takes place upon the

Altar of Zeus makes it a grave sacrilege. Indeed, it is believed that the priest at Delphi killed Neoptolemos in retaliation for the blasphemy. Neoptolemos also kills

Polyxena, daughter of King Priam and consort of his own father,

Achilles (

this page

). And Neoptolemos himself suffers a violent death, murdered just before the altar of Apollo, which is, of course, the fire altar for all of Greece.

Heliodoros’s novel, the

Aethiopika

, describes in detail a festival honoring Neoptolemos and celebrated during the Pythian festival.

126

Throngs of youths and maidens marched all the way from Thessaly to participate in the holy rites, offering a sacrifice of a hundred animal victims (

hekatomb

) in front of Neoptolemos’s tomb. The feast seems to

have held special meaning for the young people who experienced a kind of initiation rite through procession, dance, and sacrifices.

Daughters of Erechtheus as dancing Hyakinthides/Hyades. Akanthos Column, sanctuary of Apollo, Delphi. (illustration credit

ill.92

)

Sometime during the 330s

B.C.

, when

Lykourgos was holding up the example of the Erechtheids as inspiration for the young of Athens, a unique monument showing three beautifully sculptured maidens was set up at Delphi—right in front of Neoptolemos’s hero shrine (previous page). The girls were literally held aloft, supported by a high pillar standing some 14 meters (46 feet) tall, reaching the height of the Apollo temple itself. Facing outward, their backs joined to the column from behind, the maidens seem to hang in the air, their diaphanous, knee-length dresses fluttering in the breeze. The tips of their toes are pointed downward, hovering just above a ring of large, unfurling akanthos leaves, exquisitely carved in lush, teeming foliage. But the apparent fecundity of the akanthos plant belies a darker meaning; we know by now that the akanthos signals

death.

The Akanthos Column is one of the most enigmatic monuments to survive from the sanctuary of Apollo.

Gloria Ferrari has identified its three maidens as the daughters of Erechtheus shown catasterized as the dancing star cluster Hyades, set in the heavens by Athena herself, as we have seen at the end of Euripides’s

Erechtheus.

127

The column propels the girls into the sky where they belong, joined in an eternal circle dance among the stars as the Hyakinthian goddesses. Their heads are crowned with basketlike diadems resembling those worn by

kalathiskos

, or “basket” dancers. We can picture the maidens of Heliodoros’s

Aethiopika

, those who danced their way to Delphi with trays and baskets upon their heads, reaching their destination at the shrine of Neoptolemos, beneath the image of the dancing Erechtheids. Here, they may have joined hands in a circle dance, imitating their heroic role models, who floated high above them.

The Akanthos Column ultimately derives from the long tradition of setting images up on tall pillars within Greek sanctuaries, winged figures that appear to fly. Just as the great Archaic sphinx, dedicated by the people of Naxos at Delphi, hovered high beside Apollo’s temple (see its location on

this page

), so, too, the dancing Erechtheids hung in the air atop the Akanthos Column. And like the flying Nike of Paionios set in front of Zeus’s temple at Olympia (

this page

), the Akanthos Column reminded all who passed, friend and foe alike, of the supremacy of Athens and the enormous sacrifices made to achieve this. Each girl raises

her right arm to support a great bronze tripod, lost long ago. It has now been shown that this tripod was further surmounted by a stone

omphalos

, the very symbol of Delphi as center of the Earth.

128

Over time, Neoptolemos develops into a model hero for young men, just as the daughters of Erechtheus do for young women. In fact, the very name Neoptolemos means “young warrior” or “recruit.” And like other heroes encountered in this chapter, he acquires a second name:

Pyrrhos.

129

This means “fire” and further links Neoptolemos to the fire of Apollo’s

altar, just meters from his tomb. Importantly, the name also connects him with

Pyrrha, wife of the Athenian

king Deukalion. The chest in which Pyrrha and Deukalion took refuge during the great flood, in fact, came to rest atop

Mount Parnassos, just above Delphi. The name Pyrrhos thus associates Neoptolemos with the Athenian royal family and may help to explain why the Akanthos Column and its dancing Erechtheids were placed so close to the hero’s shrine (

this page

).

Two key memorials were thus intentionally juxtaposed at Delphi. One commemorated the archetypal young warrior: bold, ruthless, and “fiery.” The other celebrated the archetypal maidens: graceful, elegant, yet no less brave and tenacious in giving their lives to save their city. Indeed, both male and female role models were required in the education of young citizens, in shaping a common

knowledge for appropriate gendered behavior, both steeped in valor and patriotism. In the shadow of Apollo’s temple and in the light of its eternal altar fire, youths and maidens sang, danced, and sacrificed. The shrine of Neoptolemos-Pyrrhos and the column of the dancing Erechtheids above it served as a key destination for young pilgrims at Delphi, especially those from Athens, a place where they performed special rites of initiation and reinforced their identities as Athenians in full view of all.

YOUTHS AND MAIDENS PERFORMED THESE

rites in preparation for their future lives in which war,

death, and remembrance would figure so centrally. These forces were as powerful in the shaping of the youthful psyche as in the formation of Greek sacred spaces and the monuments that filled them. As festive and joyful as the atmosphere of holy shrines might have been, energized with processions, singing, dancing, and other spectacles, we must remember the darkness that otherwise

overhung daily life: the darkness of incessant warfare and of primordial self-sacrifice, both of which made that life possible. The aching

memory of lives lost by every single family who entered the holy precinct was carried with them up the Sacred Way.

What Athenian paideia was ultimately trying to teach was

courage. For courage was essential to survival in the brutal world that was Greek antiquity. Athenians spent two out of every three years at war during most of the fifth century. It has been argued that in this war making, Athenians understood more clearly what they were doing than others of their time.

130

For democracy fostered free speech, deliberation, and forethought, all of which clarified the reasons for one’s actions. From this, the revolutionary ideal of self-sacrifice for a greater good was born. Piety, paideia, and ritual tradition fueled the bravery needed to sustain this ideal. And it is this courage that enabled Athenians, old and young alike, to face the enormous challenges that winning and defending democracy so urgently required.