The Parthenon Enigma (51 page)

Read The Parthenon Enigma Online

Authors: Joan Breton Connelly

As they performed behind the northern ramparts of the Acropolis, the girls would have looked up at an astounding celestial display. The upper culmination of the star group

Drako, the Serpent, coincided precisely with the period during which the Panathenaia was held. It is, as

Efrosyni Boutsikas has pointed out, no coincidence that the final days of the Panathenaic festival overlapped precisely with this most significant astronomical phase of Drako, the serpent killed by Athena in the cosmic battle of the gods and the Giants, a boundary event vibrantly commemorated in this sacred feast.

77

By the time the

pannychis

commenced, Boutsikas observes, the

constellation would have been visible in an upright position, having just crossed the meridian.

During this annual culmination of Drako, its two brightest stars, those located in the Serpent’s head, would have been best viewed from the

north porch of the

Erechtheion.

78

And so, if we locate our “theatral space” just beside this porch, the singing and dancing of Athenian maidens would be situated directly beneath this astral spectacle. (A fascinating parallel, the constellation Hyades, the same as the star group Hyakinthides into which the daughters of Erechtheus are catasterized, is best viewed from the area east of the Parthenon and altar of Athena.)

79

Of course, the suggestion that the choral dances of the

pannychis

took place in a theatral square at the north of the Erechtheion is purely speculative. It is impossible to prove that a space was used for dancing in the absence of live performers. Nonetheless, consideration of open spaces where spectacles might have occurred repays the effort and teaches us much about ritual circulation and movement. Indeed, ritual kinesis shaped sacred spaces that today sit silent and elusive, void of the action that defined their original function. The archaeological imagination can come alive through the integration of the visual, the acoustic, the

mythopoetic, the architectural, and the topographic to bring deeper understanding of the experience of place and time within the ancient landscape.

80

AS DAWN BROKE

the following day, marchers would assemble just outside the city walls in the Kerameikos to begin their Panathenaic procession. There the crescent moon hanging in the eastern sky would fade away as the heavens lightened. The parade route stretched roughly one kilometer, starting at the Dipylon Gate, crossing the Agora, and climbing the Acropolis (insert

this page

, top). The

Sacred Way measured ten to twenty meters in width to accommodate the great number of processionists.

81

The honor of leading the marchers was reserved for a young woman of

parthenos

status, that is, a girl just past puberty but not yet married. She was handpicked by the chief magistrate himself from among the daughters of the oldest families in Athens.

82

It was a great distinction to be singled out in this way as one of the fairest daughters of the city’s elite. It was the responsibility of this young woman to carry upon her head a basket containing the implements of sacrifice: knife, oils, ribbons, barley. One wonders if the visual spectacle of a young parthenos, leading the procession and carrying the sacrificial paraphernalia on her head, might not have somehow evoked the

memory of one very special parthenos who, in deep antiquity, marched (with all eyes upon her) to the

altar of Athena for sacrifice at her father’s hand.

An Attic black-figured cup, dating to the mid-fifth century, shows just such a basket bearer approaching a flaming altar within Athena’s sanctuary. The goddess and her priestess stand behind the altar while a man leans over it to shake the priestess’s hand (insert

this page

, top).

83

What are we looking at? Raising her arms to steady her burden, the little

basket bearer is clearly the leader of the procession of sacrificial victims (bull, sow, and ram), musicians, and soldiers that follow behind her. Here, the deep past and the contemporary rituals that commemorated it merge in an

iconography that accesses both mythical times and the historical present.

One cannot help but notice a certain correspondence between maiden basket bearers and the sculptured karyatids that first appear in Greek sanctuaries in the sixth century, when sacred spaces were formalized on a monumental scale.

84

The richly dressed karyatids of the

Siphnian Treasury

at Delphi, for example, show high basketlike elements upon their heads.

85

These so-called

kalathos

(basket) karyatids may reflect the appearance of actual young women who circulated past them on festival days, leading processions up the Sacred Way.

86

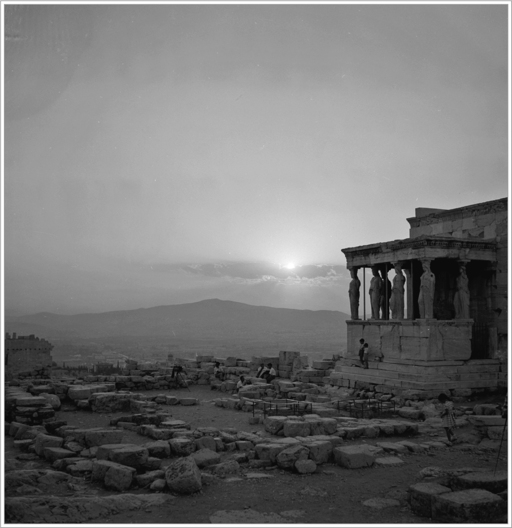

The same can be said for the karyatids of the south porch of the Erechtheion (facing page). Atop their heads are pads that cushion the weight of the lintel. Shown dressed in their festival finery, the Erechtheion karyatids served as mirrors in marble for the maiden basket bearers who led processions up the Acropolis.

87

The aim of the procession was, after all, to invite the deity to the festival. By making the pageant continually present through the permanent fixtures of karyatids, Athenians would have rendered the invitation to

Athena perpetual, and with it the goddess’s benevolent presence.

88

Sacred images carried high in processional display would have met the karyatids at eye level and, perhaps, have been seen to interact with them. It is helpful here to consider the great temple processions of southern India that, to this day, transport statues of divinities along sacred parade routes, stopping at station points along the way.

89

In the

Chittirai festival at

Madurai, statues of the goddess

Meenakshi and her consort Shiva perambulate across a cultic landscape before they are installed at the inner sanctum of the temple. At the Meenakshi-Sundaresvara temple, stone images of King

Tirumalai Nayak and his wives emerge from the architecture to become one with the processions that pass before them.

90

This model can help us understand how the Erechtheion karyatids functioned within their ritual space. Each year at the

Plynteria, or “Washing,” festival, the olive wood statue of Athena was taken from the Acropolis and transported to

Phaleron for bathing in the sea. Held high in sacred procession, it would have been carried right past the Erechtheion karyatids, at their eye level, allowing for a kind of sacred dialogue between the stone maidens and the goddess’s image.

Karyatid porch of Erechtheion, from southeast, Athenian Acropolis. © Robert A. McCabe, 1954–55. (illustration credit

ill.98

)

THE DAY FOLLOWING

the Panathenaic procession, that is, the seventh day of the festival, saw two great tribal contests: the

apobates

race and the boat races. Considered the “noblest and grandest of all competitions,” the

apobates

race required a charioteer to drive four horses at full speed while an armed

hoplite jumped in and out of the chariot.

91

In principle, this mimicked the actions of a warrior in battle, but as we have noted, the days of chariot warfare were long past. Like other tribal events, the

apobates

race evoked the days of early Athens and the exploits of the ancestors.

As observed, the founder himself,

Erechtheus/Erichthonios, introduced the chariot to Athens and competed in a chariot race at the very first Panathenaia. The fact that the

apobates

race concluded at the

City

Eleusinion highlights a special connection between this event and the defeat of Eumolpos. We have already noted that the Panathenaic procession takes a special detour around the City Eleusinion on its way up the Acropolis (insert

this page

, top). This was perhaps done as a nod to Eumolpos, who went on to play a central role in Eleusinian cult.

The tribal regatta held the same day at Munychia Harbor in the Piraeus was, in essence, a mock naval battle. We are told that the tomb of

Themistokles was positioned with full view of these rowing races, which surely commemorated Athenian victory at the

Battle of Salamis, a monumental triumph won under his leadership.

92

As with other tribal contests, the prize for the boat races went to the entire team rather than to an individual winner. First prize consisted of three oxen, a three-hundred-drachma cash award, plus another two hundred drachmas set aside “for banqueting.”

93

From this we can infer that the winning tribe enjoyed a great feast of ox meat following their victory.

MUCH AS WE MAY

try to reconstruct the days of the Panathenaia, a central mystery remains: Just how did the ancient Athenians themselves understand their most important festival? What, in their view, were its origins, and how did they comprehend the meaning behind the rituals they practiced so faithfully for nearly a thousand years? This was, after all, a culture intensely pious and obsessively aware of its past; its understanding might have shifted over centuries, but in such a world there is no place for mere traditions, custom for its own sake. Yet recovering the contemporary understanding is frustrated by a problem inherent in ancient

religions: those bound by a shared system of beliefs rarely have cause to describe them. It is mostly from outsiders looking in that we learn about a community’s religious practice.

94

But there were no outsiders then writing about Athenian cult ritual.

Late-nineteenth-century scholars, eager to explain the Panathenaia, seized upon the

birthday of Athena as the occasion for the festival.

95

Despite immediate protests from

August Mommsen, the brother of the great

Theodor Mommsen, the only classical scholar ever to win the

Nobel Prize in Literature, this idea was generally accepted.

96

Over the course of the twentieth century it became “established fact,” with some scholars still holding to the notion even today. In fact, though, despite knowing so much about it, we are at a loss to definitively explain the reason for the Panathenaia, a cause for chagrin. Some have interpreted it as a kind of New Year’s festival; others as a celebration of the new fire.

97

Noel Robertson has neatly summed it up this way: “Although so many details are so well illuminated, the center is dark. There is no understanding of the origin and significance of the festival, of its social or seasonal purpose, and there has been almost no inquiry.”

98

One alternative to the birthday-party hypothesis has gained strength in recent decades. This view holds that the festival commemorated Athena’s victory in the

Gigantomachy.

99

To be sure, the battle of the gods and the Giants looms large in Acropolis ritual and

iconography. It was spectacularly displayed on the Old Athena Temple at the end of the sixth century (

this page

). That this episode from cosmic prehistory was woven into the peplos offered to Athena is significant, as is its appearance in

Athenian vase painting from the mid-sixth century on, including many fragments found on the Acropolis itself. There is enough evidence, however, that the Gigantomachy, though central, is but one of several boundary events celebrated at the Panathenaia, one among a group of core narratives by which the Athenians defined themselves. In this sense, what can be said of the Parthenon can also be said of the festival, and this is no accident: it presents several pieces of the

genealogical story at once.

The foundation myth of Erechtheus’s victory over Eumolpos, and the

virgin sacrifice that ensured this Athenian triumph, is also one of these central events celebrated in the Panathenaic festival. Capping off the Late

Bronze Age, this victory joins the Titanomachy, the Gigantomachy, the exploits of

Theseus, the

Trojan War, and other genealogical myths celebrated on the Acropolis from the Archaic period on. Just as ancient Near Eastern

epic and visual culture simultaneously celebrated succession myths across a vast stretch of time, so, too, Athenian ritual commemorated a “layering” of successive local victories pushing Athenian identity further and further back into the distant past. Indeed, it would be strange if a ritual as deeply social as that of the Panathenaia could have developed without a strong mythological narrative at its core. And

so the deep history that informed Athenian consciousness was every year enacted

kinetically, just as throughout the year it was attested in the immobile marble of the Parthenon.