The Parthenon Enigma (54 page)

Read The Parthenon Enigma Online

Authors: Joan Breton Connelly

In the Greek world, owls carried a similar connotation of death, lament, and mourning. In the visual arts, winged figures often represent the human soul leaving the body. Female “

death spirits,” sometimes called

Keres, were understood to transport souls to Hades. We

find winged sirens, harpies, griffins, and sphinxes employed as guardian figures on Greek funerary monuments.

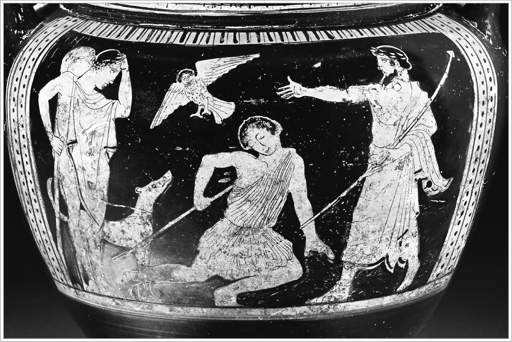

The winged soul of the dying

Prokris can be seen flying out of her body and up to the heavens on a red-figured krater in London, dating to around 440

B.C.

(below).

141

Her husband,

Kephalos, out hunting, accidentally killed her with his spear, mistaking her for a wild animal hiding in the bushes. We see him with his hunting hound, at left, while Prokris’s father, King Erechtheus, stands at right, pointing with great agitation to her winged spirit as it slips away. Prokris’s soul, shown as a woman’s head on a bird’s body, faces the viewer head-on, just like the lifeless face of the woman left behind, the two together telling of the ineffably altered state that is death.

The owl’s role as harbinger of death holds the key to its close association with Athena. We have seen that the word

ololugmata

, the shrill wailing of women at times of sacrifice and death, provides the root for the word “owl,”

ulula

in Latin and

ule

in Old English. Alkman’s

First Partheneion

, or “Maidens’ Song,” a remarkable text dated to the seventh century

B.C.

, preserves lines sung by the girls’ chorus under his supervision at Sparta:

Death of Prokris, showing her “bird-soul” leaving her body while her husband Kephalos and father Erechtheus watch. Column krater, by Hephaistos Painter, ca. 440 B.C. (illustration credit

ill.103

)

I would say I myself,

a maiden, wail [

lelaka

] in vain from the sky,

an owl [

glaux

].

Alkman,

First Partheneion

85–87

142

Gloria Ferrari points to an important connection between the girls’ chorus that sings this song and the Hyades, the inconsolable nymph sisters who mourn the death of their brother,

Hyas, killed in a hunting accident. Known for their weepy raininess, the Hyades become the archetypal singers of dirges, engaged in eternally funereal lament. In the “somber, relentless quality of the night owl’s hooting,” Ferrari hears the “mourning voice” of the Hyades.

143

Their grief culminates in their transformation into the star cluster Hyades, a

constellation that is further associated with the dead daughters of Erechtheus, catasterized as the Hyakinthides. Some of the final lines preserved in the fragments of Euripides’s

Erechtheus

give the words “to/for the Hyakinthides,” and “stars.”

144

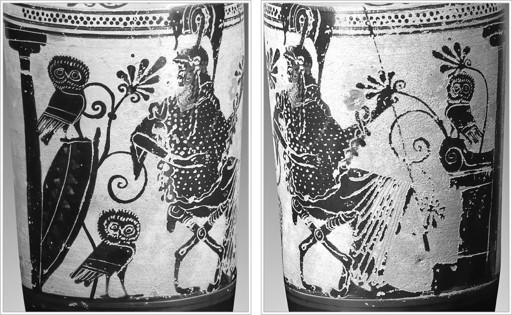

In Athenian vase painting, we find a number of intriguing images that show Athena in the company of three owls. A white-ground

lekythos in Kansas bears the image of a helmeted Athena seated within her sanctuary (facing page).

145

One owl alights upon her shield, another stands beneath it, and a third perches atop her

altar. When the image is read as the souls of the three daughters of Erechtheus, the owl on the altar can be seen as the maiden who was sacrificed (on Athena’s altar) while her sisters, who kept their oath and died as well, are paired together at the left of the scene (as we see them on the Parthenon frieze, set apart from their little sister). The dead heroines are shown on the vase as winged souls, their bodies lost but their spirits living on within the sanctuary of Athena. In this, I build on Ferrari’s interpretation, whereby she associated these owls with the daughters of Kekrops.

146

I argue instead that they represent the daughters of Erechtheus, who are, after all, related to and (in the ancient record) often confused with the Kekropids.

A hydria in Uppsala, Sweden, makes the connection even more emphatically. Here, a single owl perches atop an altar within Athena’s shrine, signified by a

Doric column (insert

this page

, top).

147

A man leads a ram to sacrifice while a bull stands in readiness at the far right. These represent the same animal victims (sheep and cattle) that are depicted on the north frieze of the Parthenon. Remember Philochoros: “Whoever sacrifices a cow to Athena is obliged to sacrifice a ewe to Pandora.”

148

If the owl perched upon the altar represents the sacrificed daughter of Erechtheus, whose name may, in fact, be Pandora, then the ram is an offering for her, while the bull is destined for her father, Erechtheus.

Athena seated in her sanctuary with two owls by her shield, at left, and one sitting upon her altar, at right. White-ground lekythos, the Athena Painter, ca. 490–480 B.C. (illustration credit

ill.104

)

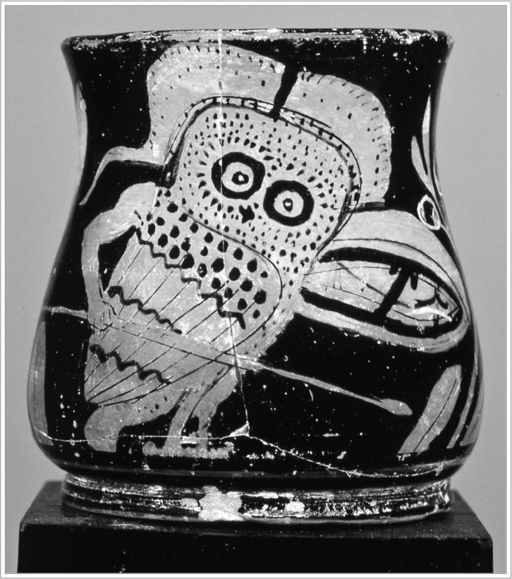

An intriguing image of an anthropomorphized owl, appearing on a mug in the Louvre, once again embodies the intimacy of Athena and the girl who gave her life for Athens (following page).

149

The wide-eyed bird staring back at us is armed and helmeted as it charges into battle, human arms emerging from its feathered body to brandish a spear and a shield (an olive frond spreads across the back of the vase). Here is a warrior owl, a predator, a bird dressed like a

hoplite. In this single image, Athena and her favorite symbol merge into one. And in their combined presence, we sense as well the soul of the little princess who saved Athens.

Praxithea likened the sacrifice of her daughter to sending a son into battle: heroism such as few girls could accede to but one to equal any heroic death for the salvation of the city. On this cup the sacrifice and the transformation have already occurred: the “warrior girl” is dead, and transformed; her spirit lives on as a winged owl. Flying over the battlefield, she inspires Athenian victory, just as hovering above the Acropolis, she summons Athenians to

ritual observances.

Anthropomorphized warrior owl brandishing spear and shield. Mug, ca. 475–450 B.C. (illustration credit

ill.105

)

The Louvre cup dates to the second quarter of the fifth century and is related to a series of Athenian vases known as owl

skyphoi, produced from about 490

B.C.

into the 420s, after which production relocated to the workshops of

Apulia in southern Italy. Thousands of these distinctive vessels survive, uniform in shape and decoration. On front and back they show an owl flanked by two olive twigs.

150

Many of these cups have one horizontal and one vertical handle, an unusual configuration that may have to do with a dual function. A horizontal handle might be used to bring the skyphos to a drinker’s lips, while the vertical handle might be used to pour libations upon the ground or an

altar. In

chapter 1

, we visited the so-called

Skyphos Sanctuary on the

north slope of the Acropolis. Here, over two hundred cups of skyphos shape were found deliberately arranged in rows, perhaps reflecting how worshippers performing such a ritual set down their cups after offering a libation. Indeed, it is likely that the owl skyphoi were used on very specific ritual occasions.

We find yet another anthropomorphized owl on a tiny terra-cotta loom weight from

Tarentum in southern Italy (facing page), now in the Art and Artifact collections at Bryn Mawr College.

151

As on the owl mug in the Louvre, human arms are seen to emerge from the bird’s body. The owl is busy spinning, lifting a distaff as it draws wool from a basket down below. Form, function, and decoration meld seamlessly in this object: when suspended in air from the loom, dangling on threads, these little owls would appear to fly. Imagine the tiny fingers of a girl weaving the weft through the warp, tickling the threads and causing the owls to dance in the air.

Girl owl with human hands spins thread on distaff. Terra-cotta loom weight from Tarentum. (illustration credit

ill.106

)

No class of objects, however, made for a wider dissemination of Athena’s companion than the large silver

tetradrachms, known simply as “owls.” Minted without interruption from the last decade of the sixth century until the first century

B.C.

, these coins and their contemporary imitations circulated as far away as Yemen and Afghanistan.

152

They present Athena on the obverse and, on the reverse, her owl, an olive sprig, and the letters

ATHE

(an abbreviation for the words “of the Athenians”). Some specimens show the crescent moon in the field just to the left of the owl’s head (following page), a device that, we have argued earlier, may well signal the Panathenaic festival itself, a feast that culminated on the day the moon waned. As the quintessential Athenian celebration, the

Panathenaia was so synonymous with Athens that the crescent moon communicated what the city was best known for. In Aristophanes’s

Birds

, the owl coins are famously referenced when

Euelpides asks, “And who is it brings an owl to Athens?”

153

This can be understood as a kind of “coals to Newcastle” joke, hilarity at the thought of bringing to the city the one thing it was awash in.

AS NOTED

at the opening of this chapter, the Panathenaia was not the most important event in Greece, but it could not have been more important at Athens, as the ultimate rite of belonging. We have focused on the singular role of the tribal events, competitions, and rituals that set the Panathenaia apart from all other Panhellenic festivals. These represent a manifestation of a larger Athenian obsession with genealogy that we have tracked throughout this book. Legitimacy of descent was the sine qua non of membership in the citizenry.