The Potluck Club (10 page)

Authors: Linda Evans Shepherd and Eva Marie Everson

Tags: #ebook, #book

Leigh smiled at Donna. “That’s right. I just flew in yesterday.” I leaned back in my chair and almost let my happy sigh escape my lips. This was perfect. The conversation wouldn’t need much direction from me, and I could concentrate on studying each of these women. Though, I couldn’t help but feel sorry for Evangeline. Here was a woman who loved control, and that control had just slipped through her fingers. Which, to tell the truth, was all right with me.

Soon, Evangeline’s world would be my domain. And as for Donna, she was a woman who ate a meal without so much of a prayer or blessing. There was a lot more to her than her dear Grace Church friends suspected. I detected a lot of pent-up anger. But why? A dark secret, perhaps? Whatever it was, not only was I going to find out, I would somehow manage to give her a much-deserved makeover. I could hardly wait to get started.

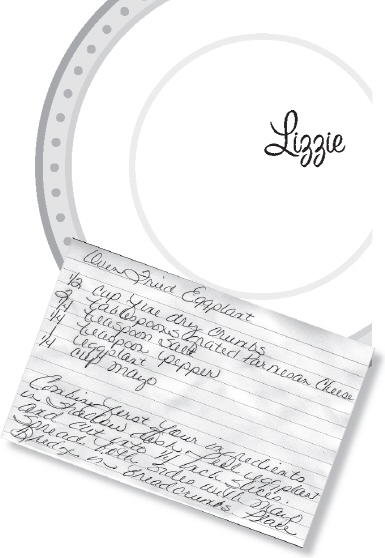

Clay had seen Lizzie Prattle in the Higher Grounds Café earlier that day, so he knew the Potluck Club had been canceled. The news had caused a bit of a stir among those, like him, who were sitting there nursing hot cups of coffee and finishing off plates of the daily breakfast special.

“Everybody knows that Evie doesn’t call off the meeting for just any reason.” Sal, the owner of Higher Grounds, was poised with coffeepot in hand as she refilled his cup for the fifth time that morning. “That’s just odd,” she continued. “Wonder what’s going on over at Evie’s?” “Maybe she’s not feeling well. Cold weather coming in . . . some people are getting sick,” someone from behind Clay said, though he wasn’t sure who.

Lizzie shook her head. “Evie’s fine. Whatever the reason, I’m sure it’s a good one.”

But when Clay saw Lisa Leann’s car heading toward Evie’s side of town, he spoke out loud but to no one in particular. “There goes trouble.” In spite of himself, he chuckled a bit.

For a little bitty

thing,

he thought,

that woman carries a lot of nerve.

Not too much later, Donna’s Bronco passed by the café, heading in the same direction. This time, Clay nearly fell out of his chair. “What’s so funny?” Sal asked from the counter.

He shook his head. “Nothing,” he answered. “I just got a mental picture of three hens fighting in a coop.”

Sal frowned. “You need help,” she said.

“Someone does,” he said, reaching for his notebook and pen. “But it’s not me.”

It didn’t take long after our canceled Potluck Club meeting for us to know why the postponement. Evie’s niece coming to town seven months pregnant jolted us to no end; I won’t lie about it. After all, this was Leigh whose swollen belly we were suddenly staring at a whole day later in the middle of the church parking lot. Leigh, who’d come to visit every summer and who’d played with my own daughter, Michelle.

Michelle and Leigh are the same age. When Leigh came to visit Evie alone for the first time, the girls were about eight years old. Evie explained to Leigh that there was a little girl she could play with, but that the little girl—my daughter—was deaf. Couldn’t hear sounds and couldn’t speak well enough to always be understood, though she does have a voice. I think it’s a beautiful voice.

Leigh wasn’t the least bit intimidated by this. We brought the girls together, my old chum and I, and allowed their hearts to blend in a very special way. In no time, Leigh was attempting to learn sign language, and by the end of the summer she’d pretty well mastered it. For Michelle, it was more than merely gaining a new friend, or even a hearing friend. Michelle attended Denver Institute for the Deaf in those days, so she had plenty of deaf friends. They seemed to have so much in common.

The girls loved Barbie. And Cabbage Patch dolls. And biking on warm afternoons. They spoke of their friends; Michelle’s from the Institute and Leigh’s from West Virginia. During the school year they wrote letters to each other and, eventually, when personal computers became as common as television, they emailed. The passing years only added to their camaraderie. They shared favorite movies and music, stories of boyfriends and future plans.

To my knowledge, however, they’d never talked about being unwed mothers.

I asked Michelle about it as soon as we returned home from church that autumn morning.

“Did you know?” I signed to her.

She shook her head no, then started up the staircase toward her bedroom. I knew she wanted to avoid the conversation, but I worried about how this might affect her.

I reached for her hand and turned her toward me.

“Don’t walk away from me, Michelle,” I said, signing “don’t” and “Michelle” with my free hand as firmness registered on my face.

Michelle spoke out loud in a voice that, although nasal and strained, is angelic and pure. “I don’t know anything, Mom. I was as shocked as you.”

Michelle uses her voice when she’s emphatic about something, so I knew she was telling me the truth. I released her hand. “Okay,” I said.

Michelle sat on one of the stairs then, wrapping her arms around her knees, buried her head in the circle of her arms, and began to weep.

“Oh, Michy . . .” I cooed, though I knew she couldn’t hear me. I sat beside her, slipped my arm around her shoulders, and drew her close.

“I feel bad for her,” Michelle signed when she’d gained her composure.

“Me too.”

I waited, not wanting to rush my daughter’s feelings or expression of emotion. “I think I should talk with her, but I don’t want her to think I’m prying,” she signed.

I raised a finger before I signed back. “Why not go over later this afternoon . . . spend some friendship time with her . . . let her know you’re here for her if she needs you.” I shook my head. “But don’t question her. Just listen.”

Michelle eyed me funny. “You won’t beg for the answers?”

I laughed at her. “No, Funny Face. I won’t beg for the answers.” Michelle brushed her cheeks with her fingers, pushing the remaining tears away. “I love you, Mom,” she said out loud.

“I love you too,” I said as she stood and, turning, bounded up the stairs just as her father walked through the front door and found me sitting there alone.

“Let me guess,” he began. “You’ve fallen and you can’t get up?”

I smiled at the handsome devil I’d married thirty-six years ago. Though his hair is silver (well, so is mine) and mostly flushed down the drain or swept up in my Hoover, he still has a way of setting my heart to flutter. After all these years—four children and five marvelous grandchildren—he and I still desire the presence of each other over any other person in the whole wide world. “No. I was just sitting here talking to Michelle.”

Samuel’s glance went up the staircase and back to me. Joining me on the stair, he said, “I suppose you were talking about Leigh Banks.”

I nodded.

“Pastor Kevin and Jan called me into his office after the finance committee and I had finished with the morning offering to ask me how I thought Evie was handling it.”

I ran my fingers through one side of my short but full hair as I propped my elbow on one knee. “What’d you say?”

“Well, I said I thought once the shock wore off she’d be okay . . . but we certainly need to pray for her.”

“Of course.”

“I think Evie has her hands full right now. She’s always put Leigh on such a pedestal. She probably never expected to have to deal with anything like this from her.”

“I might have expected it from one of Peg’s boys but not Leigh, no.”

Samuel reached over and kissed my cheek. “We know how Evie feels, don’t we, Mother?” He stood and began to ascend the stairs.

“I’m going to lie down for a while. Want to call me when lunch is ready?”

“

Want

to or

will

I?”

“You know what I mean,” he said with a chuckle.

I listened to his footsteps as he mounted the thickly carpeted stairs and then finally disappeared down the hallway toward our bedroom.

Yes, we did know about that; we weren’t the first and we obviously wouldn’t be the last. Although the Brightmans and the Fairfields were the first in our church community to struggle with it, our youngest son, Timothy—now thirty-one and most commonly called Tim—and his lovely wife “had to get married,” as they say. They’d been high school sweethearts and went off to college together, and while they swore they lived in their separate apartments, Samantha’s mother and father felt as we felt: the kids were managing to live together behind our backs.

Who could have predicted that by their junior year of college they would have a little one to prove it? Of course, by the time the baby was born, they were married and more than a little repentant. Today they live in Baton Rouge and have two children—a boy and a girl—so their little family is complete.

Samuel and I have two other children—Samuel Jr. (whom we call Sam) is thirty-three and Cindy (whom we call Sis) is thirty-one. Tim is also thirty-one—and no, they aren’t twins. For the life of me, I don’t know how I managed to give birth to two children within the span of a twelve-month period, but I did. More than that, I’m not sure how I managed to raise three children with just under three years’ difference in their ages.

Then, five years later, when I thought I’d finally be able to catch my breath, Michelle was born, bringing a whole new set of worries and concerns. But God has been faithful and good. As the psalmist said, “His mercy endureth forever.” Though I had a pack of children and a husband with the all-important job of Gold Mine Bank and Loan president, I was equally blessed to be the high school librarian, which meant I got summers and holidays off to be with my babies. I taught them the joy of reading, every year encouraging them to win a star-studded certificate from the Summit View Public Library as the top readers in Summit County, which they did, Michelle more than the others. I suppose with her hearing loss, the world of books opened up exciting possibilities to her.

Like me, Michelle is fond of both the Little House books and the Green Gables series. Last year, for Christmas, she gave me a collection of short stories by Rose Wilder Lane, daughter of Laura Ingalls Wilder and great author in her own right, which thrilled my heart.

We also enjoy the works of Daphne du Maurier and the Bronte sisters.

Michelle and I are simply old souls living in contemporary bodies.

Michelle did go see Leigh. As I promised, I didn’t pry my daughter for information. I did, however, drive over to Evie’s Monday afternoon as soon as I got off from work. In her hospitable way, she offered me a cup of coffee and some homemade tea cookies.

“Leigh made them,” she said.

“I figured,” I said as I took a seat at the kitchen table. Evie gave me one of her looks. “What?” I asked. “Like I don’t know you?”

She nodded her weary head then, casting her eyes to the countertop, where she had set large Dollar Bonanza mugs, asked, “Lizzie, what in the world am I going to do?”

I stood, walking over to her, and placed my hand on her back. “About Leigh?”

She cut her eyes over to me. “No, Lizzie. About the price of tea in China. Of course about Leigh.”

I gave a quick look over my shoulder. “Where is she now?”

“Out taking a drive. Said she just needed some air.”

“Oh,” I said. “Well, it’s a nice day for it.” The coffeemaker coughed and sputtered as it dripped its last drop of aromatic brew. I jerked the pot out and began pouring while Evie walked over to the fridge for some milk. “Has she said anything about the father?” I replaced the coffeepot and then walked the mugs over to the table, where Evie was already sitting, folding two napkins from the napkin holder that set in the center.

“Only that—and I quote—‘it’s over.’”

“How can that be? She’s pregnant with his child, isn’t she?”

Evie began preparing her coffee to her liking, and I did the same. “That’s what I said. Apparently he’s a businessman. Successful, she says. And wants to take part in the baby’s life. Support the child financially. Have visitation rights.” Evie’s shoulders sagged. “What kind of world are we living in, Lizzie Prattle?”

“You tell me,” I answered, taking a quick sip of the hot coffee. “I work at that school every day, and I am here to testify that the children of today are only getting worse. I am fifty-eight years old, and if I can hold out four or five more years, I can retire and be done with the whole lot of them.”

Evie patted my hand. “How’s Samuel?”

“Good, but don’t change the subject. Let’s talk about what we can do for Leigh.” I took another sip. “Other than pray.”

Evie swallowed a gulp of coffee. “Did I tell you that busybody Lisa Leann Lambert showed up here on Saturday?”

“No!”

“Yes.” Evie shook her head, then began a high-pitched, drawling imitation of our newest member. “‘I heard you had company, and me with all this hot barbecued brisket and homemade apple cinnamon bread, I

had

to drop by. That’s okay, isn’t it?’”

“She’s up to something, that one is.”

“Like I don’t know it. And then, to make matters worse, here comes Vernon’s daughter. Didn’t listen to her answering machine, my great-aunt Martha.”