The Puzzle of Left-Handedness (20 page)

Call it a historical coincidence, or even in the words of Stephen Jay Gould a ‘glorious evolutionary accident’, but that brain capacity was available. Roughly in parallel with the rapid spread of our early ancestors across the globe, an equally rapid, hugely impressive expansion in their brain mass took place, the first phase of growth that would culminate in the almost one and a half kilos of grey matter housed in the skull of the average modern human. Our new capacity to calculate could not have arrived at a better moment.

Well-aimed throwing is a typically one-sided affair. Its great speed and precision, and therefore the considerable firepower it provides, are achieved by the use of one or other arm as a sling. This means that the required computing power needs to be present in one side of the brain only. Nevertheless, the symmetrical structure of the physical human being meant that the other side of the brain increased in size to almost the same degree. If that capacity was not needed for throwing, it would be available for other skills that conferred evolutionary advantages of their own. Were the throwing capacity to be lodged in both halves of the brain, it would mean extra investment and the use of additional brain-power without much to show for it. After all, a person who can throw equally well with either hand is barely any more effective than someone who can throw accurately only with one or the other. The two-handed thrower may even be worse off, because of the need to choose which hand to use at a point when every millisecond counts.

All this, Calvin argued, sowed the seeds of an increasing dissimilarity in functions between the two cerebral hemispheres, possibly even for the developmental boom in the human brain that eventually produced consciousness, language and all the other characteristics that make us what we are today. At the same time, inevitably, we developed a hand preference.

Of course Calvin’s line of reasoning did not emerge out of thin air. He was inspired above all by what we know about the differences in function between the two halves of the brain. It does indeed seem as if, generally speaking, the left cerebral hemisphere is devoted to the kind of tasks in which the precise sequencing of acts and calculations is of importance. This fits in with the fact that humans are predominantly right-handed, since the left half of the brain controls the right half of the body. But now we are starting to get ahead of the argument. Calvin’s reasoning offers a fair explanation as to why only one half of the brain specializes in this kind of task, and therefore why we have a hand preference, but his story has nothing to say about which of the two halves would be best. It therefore leaves us with the mystery as to why nine out of ten people have the same hand preference. In other words: what is it that makes the left side of the brain the seat of the throwing mechanism in almost all cases and not the right, or one side in half of us and the other side in the rest?

In his search for an explanation, Calvin joins those who turn to the carrying habits of mothers with children and the position of the heart. As we have seen, most mothers carry their children with the left arm, probably because babies are happiest there and therefore quietest, since a mother’s heart is more clearly heard on the left side of her chest cavity than the right. Calvin assumes that

erectus

women were just as active during a hunt as their menfolk and that they carried their offspring with them while hunting, so women with quiet children had a clear advantage. Not only could they move more easily, there was less chance that their positions would be given away by the crying or crowing of their infants as they crept up on their prey. Those quieter children were generally carried on the left, leaving their mothers’ right hands free. So it was not the first stone-thrower but the first stone-throwing woman, Calvin’s ‘Throwing Madonna’, who took the decisive step on the road towards the modern human being.

There seems to be little arguing with the first part of Calvin’s story. It’s both appealing and based on facts. Clearly the forerunners of modern man, once they had climbed down out of the trees, spread across all kinds of terrain without having any special tools at their disposal and started eating more meat. It’s undoubtedly the case that brain size increased spectacularly in the same period, and we can throw incomparably better than our closest relatives in the animal kingdom. Finally, it has gradually come to be accepted as a fact that in the vast majority of people living today the left half of the brain is responsible for activities that involve careful planning, considerable speed and correct sequencing. Until someone throws a spanner in the works, therefore, we can assume that his explanation for the existence of hand preference holds water.

The same cannot be said of Calvin’s story about why most of us are right-handed. It relies upon assumptions about the social role of

erectus

women that are impossible to prove and against which various counter-arguments can be put. Firstly, the advantage to right-handed women who carry their infants in their left arms ceased to apply once children were no longer taken hunting by their parents. We don’t know when this happened. Secondly, we may well wonder whether hunting did not involve such risks to mother and child that women had the best chance of survival if they left it to men and the childless, relying on the solidarity of the group. Occasional examples in the animal kingdom suggest this is the way it worked.

Calvin’s idea also fails to chime with the fairly well-substantiated theories put forward by Richard Wrangham, an American biological anthro pologist who sees in the sharp contrast between

Homo habilis

and

Homo erectus

the beginnings of cookery. He claims this was an activity that fell to women from the start, partly because they were less mobile as a result of their roles in procreation and childrearing. Based on ideas about precisely the period in which Calvin looks to huntresses as the motor for one-sided brain development, Wrangham places women at the kitchen stove for the rest of eternity.

There is a fourth objection. If the behaviour of a child truly had such a powerful influence on the hunting success of its mother, then the effect on the survival chances of the child itself would be just as significant. In that case, why was the behaviour of the mother rather than that of the child subject to evolutionary pressure? If Calvin is right, you would surely think that quiet children of right-handed mothers had the best survival chances, and therefore tended to survive in greater numbers. It would therefore be perfectly sensible to suppose that modern babies ought to resemble their quietest ancestors and lie absolutely silently in their mothers’ arms. To the chagrin of many parents, this is not the case. Babes in arms still shriek, whine and wriggle to their hearts’ content.

25

Thinking About Brains

It seems natural to assume that hand preference could have something to do with the difference between the two halves of the brain. Yet it was not until well into the nineteenth century that the connection was made.

Hippocrates, the patriarch of doctors, suspected 2,500 years ago that brains were associated with thinking. That was anything but an obvious assumption. Aristotle, for instance, believed that the warm, beating heart was the centre of everything. He regarded the brain as no more than a system for cooling the blood. Yet even in the ancient world some real, concrete knowledge was available about how we control our limbs, for example. In the third century

BC

, Alexandrine scholars Herophilus and Erasistratus discovered the nervous system and were able to distinguish between efferent and afferent nerves. The former are the lines of communication that send instructions to the muscles, while the latter respond to external stimuli by transporting signals to the spinal cord and from there to the brain.

Some four centuries later Galen, the Greek personal physician to Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius, performed experiments on animals in which he partially severed their spinal cords in various places. This revealed a great deal about the composition and function of the nervous system. He also knew that the brain had something to do with the mind, but he thought the mind was to be found in the fluid that fills the hollow spaces between the cerebral hemispheres. That idea would persist until the sixteenth century, when the brilliant Flemish physician Andreas Vesalius showed it could not possibly be true. There are those who claim that as early as the first century ad people knew that the left half of the brain controlled the muscles of the right half of the body and vice versa, but we cannot be certain of this.

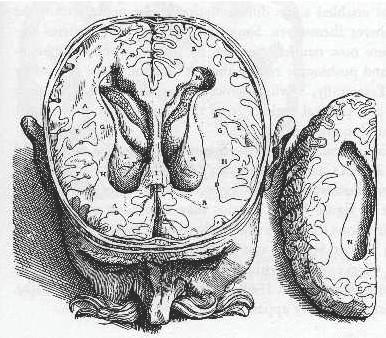

One of the drawings of the brain made by the great anatomist Andreas Vesalius (1514–1564). At the centre are the ventricles, filled with cerebrospinal fluid.

These were impressive achievements, of course, but after Galen hardly anything happened in the field of brain research for almost 1,500 years. The dissection of animals, living or dead, in order to investigate their inner structures had virtually gone out of fashion even in Galen’s time and it would be almost unknown for centuries, making way for all kinds of speculative theories that in the end produced hardly anything useful. Still, it’s possible this was of little consequence for the growth of knowledge about how the brain works, since across all those centuries a range of dogmas, most of them emanating from the churches, blocked the free development of ideas about the connection between our bodies and our mental processes. The mind, the spirit and the soul were things of a higher order, mysteries that must at all costs remain mysterious. In any case people had few techniques, however primitive, that would have enabled them to study the brain, and there is nothing to be seen in the grey matter itself that could possibly divulge how it works. A damaged brain, like a diseased heart or failing kidneys, caused death. Why this was so inevitably remained a mystery.

The idea that the brain has something to do with thought, emotions and the intangible thing we call the mind nevertheless remained alive down through the centuries. A strange grey lump of matter fills the head, while the face is the location of our most striking features and means of contact with the outside world. Throughout history, people have believed that a person’s character and intelligence could be read from his or her face. Aristotle, who felt his own appearance to be no better than ordinary, publicly declared that he had his training in philosophy to thank for the fact that his mind was less ordinary than his face would suggest. It’s an extremely deep-rooted notion, as evidenced by the success of comparable ideas presented by Cesare Lombroso in about 1900, to which we shall return.

| Even Vesalius’ skeletons wondered what was going on inside the brain. |  |

The turning point came in the eighteenth century, with the success of the Enlightenment. The most important achievement of that school of thought was to dispense with traditional, mainly religious convictions. According to the philosophical innovators of the time, the nature of things could be discovered through reasoning, aided by empirical science. In other words, people no longer wished to speculate randomly, nor to adhere to an unquestioning faith in the old, respected authorities simply because they were old and respected. From this point on, the message was: look carefully and draw rational conclusions from what you see. Whether or not God and the pope were pleased by this approach no longer really mattered to serious scientists, who were now free to start examining those aspects of humanity that had to do with the mind.

It wasn’t long before a great many people started studying the brain, among them the Viennese doctor and anatomist Franz Joseph Gall (1758–1828). He was the first to claim that our brains consist of a layer of grey matter, the cerebral cortex, over a core of a whiter substance. He was also a central figure in phrenology, a movement that had been gaining in influence ever since the mid-eighteenth century and from which many of the terms and concepts used in today’s psychology are derived, as well as a whole series of misconceptions and popular fallacies. Phrenology was the first real attempt to link human functions and behaviours with the brain. It was based on the notion that specific human characteristics were anchored in specific parts of the brain, and that you could see from the shape of the skull and its bumps and irregularities how highly developed, or not, certain functions were. Phreno logists were rather casual in the way they went about localizing characteristics. Gall, for example, ‘discovered’ that the centre for individuality and new ideas lay just above the nose, since, or so he claimed, that particular area was large in the case of Michelangelo but generally small among the Scots.

Phrenologists believed the brain to be a collection of more or less independent organs for characteristics such as aggression, introspection, conscience and inquisitiveness, as well as for language, a sense of time and melody, humour and wit. The larger the organ in relation to others and therefore the bigger the bump in that position on the skull, the more dominant that particular characteristic would be in the person concerned.

Although there were perhaps as many charts of the skull as there were phrenologists, they had one thing in common: all were symmetrical. On the charts drawn up by Gall, Spurzheim and Combe, exactly the same areas are marked out on the left as on the right. Gall seems to have taken it as read that his brain organs were laid down with the same mirrored symmetry as arms, legs, lungs, kidneys, Fallopian tubes and testicles. This is actually rather strange, since even though the cerebrum consists of two halves that at first sight look symmetrical, the differences between them in the twists and folds on their surfaces are considerable. As a trained anatomist, Gall must have been aware of this – especially since those irregularities were supposedly the features that told us so much.

Personality areas in the brain according to the phrenologists Gall, Spurzheim and Combe.

| There were as many sets of characteristics as there were heads. On this skull, the ‘Protestant saint’ of Alsace, Jean-Fréderic Oberlin, indicated the distribution of talents in a way that was all his own. Above the nose, where Gall locates individu ality, Oberlin identified a ‘memory of things’. |

Phrenology, therefore, was not a true science; it was more a sort of speculative sport for gentlemen of high social standing. Gall simply invented his brain organs and the places where they were located. He didn’t discover them – they were not there to be discovered. Yet al though the claims of phrenology were extremely shaky and plenty of people were aware of this from the start, the ideas of Gall and others like him were popular until the mid-nineteenth century, and not just among certain groups of neurologists and physicians but among a far broader public. For the educated citizen there could be no more enjoyable party game than determining the characteristics of your household, friends and acquaintances in a ‘scientifically sound manner’ simply by looking for irregularities on the surface of their skulls. Think of the solace to be had from the evidence-based notion that you could tell from the broad, flat head of your firm’s chief accountant that he was a crafty schemer.

After about 1820 serious opposition emerged to this brisk, unthinking phrenology, encouraged in part by the fact that another researcher, Frenchman Jean-Pierre Flourens, had noted that destruction of dif ferent parts of the brains of pigeons often had roughly the same effect. The decisive factor was not so much the location of the damage as the amount of brain mass affected. Flourens argued therefore that characteristics and functions cannot be located at specific places. The brain works as an indivisible whole. Although he rather blithely passed over the fact that birds’ brains are not at all the same as human brains, his work marked the beginning of the end for phrenology. As is often the case with scientific plausibility, the pendulum swung to the other extreme. From this point on the localization of brain functions was regarded as nonsense. Anyone who continued to believe that certain parts of the brain had specific tasks to fulfil could expect to meet with a great deal of scepticism in scientific circles.

This is probably the reason why French family doctor Marc Dax made little impression at a congress in Montpellier in 1836 with his discovery that patients with brain damage on the left side often had trouble speaking and understanding speech. This was the basis of his conjecture that linguistic functions are located primarily in the left cerebral hemisphere. He was unable to find a publisher for his work. Within thirty years the situation had changed again. In Paris in 1861, Paul Broca (1824–1880) announced the discovery of the area of the brain that is named after him. Broca reported that time and again speech problems arose when precisely that area was damaged, whereas linguistic comprehension, memory and other functions related to language might remain intact. The area he had identified must therefore be specifically connected to speech.

*

Within ten years of the publication of Broca’s work, Gustav Fritsch and Eduard Hitzig discovered the bands across the middle of each hemisphere that were responsible for the control of the limbs and other movable body parts, brain areas now known collectively as the motor cortex.