The Puzzle of Left-Handedness (16 page)

We find plenty of examples of the same type of composition in double portraits on two separate canvases. There are almost no couples in portraits in the Rijksmuseum with the man standing to the left of his wife, and none at all among those painted prior to 1700. It is a traditional arrangement that shows we are dealing with a respectable married couple, and one that still applies in the rules for formal church weddings; once the ceremony is over, the bride leaves the church on the left side of her new husband. This tradition has apparently had a profound influence not only on the double portrait but, via the double portrait on separate canvases, on the composition of portraits of lone individuals as well.

The strong tradition of portraying women with their left cheeks to the fore and men the other way around therefore seems to be derived from rituals and etiquette, but there is probably more to it than that. The phenomenon is reinforced by the influence of the angle of the light on the composition. Even in right-cheeked portraits the light generally falls from the left, so the model is looking away from the light to a greater or lesser degree. This does not necessarily mean that the face is obscured, but it does tend to emphasize the edges of the profile, strengthening the curve of the nose and the lines of the chin and forehead. This kind of lighting tends to stress sternness, willpower and other characteristics traditionally attributed to the male. The softness, roundness and elegance that are thought of as typically feminine are not aided by such angular lighting; they are more apparent when the light bathes the whole face equally, in other words when the face is turned towards the left of the picture, where the light is coming from.

So it came about that a great many posing Madonnas, in order to display their femininity and their soft features, were forced to treat their children with unpleasant severity.

*

Some experts are of the opinion that the royal couple are not the subject of Velázquez’s attention, since no double portrait of them is known and because the canvas shown in the picture is too large for a portrait. But in that case what are they doing at the spot where the model should be? Furthermore, what Velázquez professes to show,

Las Meninas

, cannot possibly have been painted from life. The fact that he was not in reality working on a double portrait therefore tells us nothing.

20

Little Johnny Cries to the Left,

Little Johnny Smiles to the Left

Human faces are remarkable things. Everyone knows that the left and right halves may differ considerably. Like the rest of our bodies, faces are only broadly symmetrical, a fact that is not without consequences. Symmetrical faces are seen as a hallmark of beauty. There’s an assumption that we can explain this in evolutionary terms. Regular features are said to indicate good health and a flawless package of genes, and people with symmetrical faces are therefore valuable partners in the struggle to reproduce.

Less well known is the fact that the two halves of the face have different roles, both in the recognition of someone’s identity and in the interpretation of his or her emotional state.

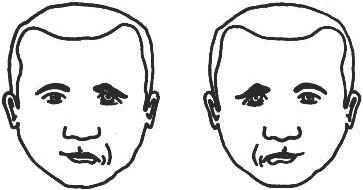

Generally speaking people can effortlessly express at least six different emotions on their faces: happiness, sadness, surprise, fear, disgust and anger. Of course we can convey more than that with our facial expressions, but these six occur in all cultures and are equally easy to produce and to recognize in every population group. Oddly enough it’s the left side of the face that does most to determine which emotions others see in it. This was made clear many years ago when research subjects were shown two pictures of a face, each the mirror image of the other and in all other respects identical, in which one side was cheerful while the other looked glum. Around eight out of ten people turned out to base their assessment of the depicted character’s mood mainly on the left side. If the left half of the figure’s face looked unhappy, people thought he was unhappy, if only the right half looked sad, he was seen as rather more cheerful.

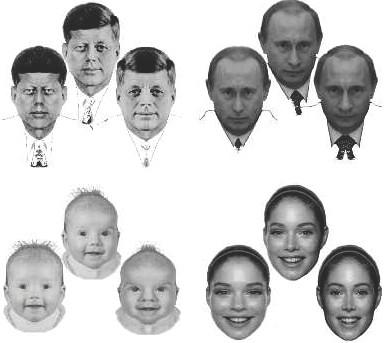

When it comes to the straightforward recognition of a person based on his or her face, the right side weighs more heavily. Tests show that people feel an image of the right half of a face filled in with a mirror image of that same half bears a greater resemblance to the person depicted than a composite photo made of two images of the left half. In some sense we resemble the right side of our faces more than we resemble the left.

Eight out of ten people feel that the face on the left looks more sorrowful than the face on the right. In fact they are identical, except that one is the mirror image of the other.

This phenomenon probably has to do with the difference between the two halves of our brains, which each have their own specialist functions. The left half of the brain is good at everything that relies upon calculation: counting, arithmetic, logical reasoning and much that has to do with language. Among the things the right cerebral hemisphere concentrates on are the interpretation, recognition and recollection of images. Of course there are a great many things that the two halves of the brain do together, if only because many complex tasks make use of simple functions, some of them located in one half of the brain and some in the other. That cooperation between the two hemispheres is made possible by connections between them at various levels, known as commissures, which work like bundles of telephone lines in a large office complex. The biggest by far is the

corpus callosum

, a broad band of tissue that is unique in making direct contact with both halves of the cerebrum.

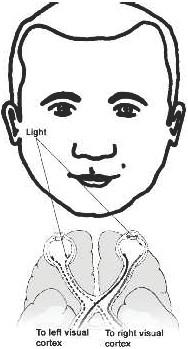

In the case of our eyes, which in a sense are bulges in the brain that stick out through the skull, information coming from the left half of each retina is initially processed by the left half of the brain, and vice versa. So if we look directly at a face, its left half, which is on the right side of our visual field, is registered on the left half of the retina and that half is therefore initially processed by the left cerebral hemisphere. The right side of the face, to the left as we look at it, is registered on the right half of the retina, which sends signals to the right half of the brain.

Four famous people and their half-faces. Clockwise from the top left the American president John F. Kennedy, Russian ruler Vladimir Putin, supermodel Doutzen Kroes and baby Cleo. In each case the middle picture shows their real face, with below it a doubled left half on the right and a doubled right half on the left. Even Kroes’s extremely symmetrical face looks more like its right half.

It therefore seems logical that we base our recognition of faces on their right side, since that information goes straight to the right half of the brain where our capacity to recognize faces is located. Information about the other side can reach that part of the brain only via a detour through the

corpus callosum

. This works fine too; we can instantly recognize a face even if its owner covers the right half, although it does take us a tiny bit more effort. Why is it then that in recognizing emotions on faces, a fairly subtle piece of interpretation based on visual information alone, we mainly take account of the left side of the face?

One explanation that has been advanced is that there is simply more to be seen on the left side of a face, since it’s controlled by the right side of the brain, the side that is more emotionally orientated. But even if this is correct it does not solve the problem. It’s certainly not the case that emotions are exclusively the prerogative of the right side of the brain and even if they were, the advantage of the greater expressiveness of the left side of the face would be cancelled out by the emotional hamfistedness of the left half of the brain, which we use to observe that part of a face. The following explanation may therefore be more convincing, although it too is based on an unproven assumption.

Cross-section of the brain in between the two cerebral hemispheres. We are looking at the right side, with the right half of the bisected

corpus callosum

at the centre. The white brain stem below it continues downwards as the spinal column.

Although emotions are not entirely the preserve of the right cerebral hemisphere, it does seem true to say that the right brain is more emotionally oriented than the left. It could therefore be the case that the left half of a face, controlled as it is by the right side of the brain, is more expressive of emotions. If so, then the right side must be less changeable. This is precisely what makes it a better guide to simple recognition: in all circumstances it looks more like itself than the left side, which has a greater tendency to change according to the mood of its owner. As an extra bonus, when we look at a person the relatively unchanging half of his or her face is connected by the shortest possible route to the portrait gallery in the brain that enables us immediately to recognize family, friends and acquaintances, which is also located in the right brain.

The left brain is better suited to the recognition of the various expressions of emotion on a face. The recognition capacity of the right brain concentrates on making a perfect match between what we see and an image stored in the memory. Fleeting variations only make that task more difficult, whereas subtle changes suit the left brain rather well. Once our right brain has determined whose face we are looking at, our left brain can compare that image with what it sees on the left side of that same face. It then needs to make a complicated subtraction sum: what the left brain sees minus the right-brain-determined standard face gives the emotion that is being expressed. This information can be elaborated further, enabling us to work out exactly what emotion we are witnessing. Although this seems to involve a lot of traffic between the two halves of the brain, each half does exactly what it’s best at: the right brain is responsible for the recognition of a face and the interpretation of emotions at a high level, while the left brain makes calculations at which the right brain is less adept. In this way optimal use is made of the information we perceive with our eyes.

| When we look directly at someone, the light from the right half of their face arrives on the right side of our retina. We therefore use the right half of the brain to ‘see’ the right half of a face. |  |