Read The Rise and Fall of a Palestinian Dynasty Online

Authors: Ilan Pappe

The Rise and Fall of a Palestinian Dynasty (60 page)

Jamal, who had testified before the commission when it visited Palestine early in 1946, had not imagined such a setback. Now he began to work quietly on a new Palestinian course of action. He asked for the British Mandate to be prolonged and called for an attempt to reach agreement in the hopes that the uncompromising Jewish stance expressed by Ben-Gurion back in 1942 would be softened.

45

When he came out after testifying before the commission, Jamal was surrounded by Jewish journalists, most of whom he knew, and was as always revitalized by such an encounter. ‘What will be the outcome of the investigation?’ the journalists asked. But Jamal preferred to discuss the situation on the ground, and he made a prognostication that would not be realized: ‘If you believe that a Hebrew state will come about, you’re mistaken. If you think that an Arab state will come about, you are again mistaken. Things will go on as before. If only the two sides, the Arabs and the Jews, had any sense, they would reach some sort of agreement.’ ‘Is it possible to reach an agreement?’ asked one journalist.

‘I believe it is,’ Jamal replied, ‘but on one condition

–

not with the existing Jewish Agency.’ ‘Nor with the existing Higher Arab Committee either,’ another journalist remarked. ‘Perhaps,’ replied Jamal on a conciliatory note. That was his last friendly encounter with the country’s Hebrew press.

46

Jamal was mistaken: the Jewish state did come about, while the Anglo-American commission became a footnote in history. Except for one of its recommendations

–

to enable the immigration of another 100,000 Jews

–

it defined the difference between the British and American positions. Bevin made one or two further attempts to keep his promise to solve the conflict, then gave up. He convened another Anglo-American commission, resulting in the Morrison–Grady Report, which recommended dividing Palestine into cantons, such as those in Switzerland, an idea that both sides rejected outright.

To conduct the negotiations, the Arab League now appointed a body that gradually displaced the Higher Arab Committee and barred it first from taking part in the diplomatic struggle for Palestine and later from preparing for the military campaign. The Syrian resort of Bludan reappeared on the map of Palestinian history. But whereas al-Hajj Amin had been an honored participant there in 1937, in June 1946 the cause of Palestine was appropriated by the Arab League. When the League met in Sofar, Lebanon, to discuss the Palestinian struggle a few months later, it did not even bother to invite al-Hajj Amin. His dismay can only be imagined, given that he had formed a close association with the Arab League when he settled in its birthplace of Cairo.

47

Jamal was more welcome in Bludan, though not more effective. He demanded that the Arab states provide military support for a revolt if an Anglo-American solution were to be forced on Palestine (based, he assumed, on the creation of an independent Jewish state). The representatives of Syria and Iraq declared their full support. Since the end of World War II, Syria had been in favor of aggressive action, though it did not support the Husaynis. The Iraqi delegates were two-faced. They supported the ambition of Transjordan’s King Abdullah, the kinsman of their Hashemite king, to take over all or part of Palestine, assuming he could reach an agreement with the Zionists. At the same time, in pan-Arab gatherings, whether secret or open, they were the keenest supporters of comprehensive military action.

48

Jamal tried to impress the delegates by claiming, falsely, that he had recruited 30,000 young men for the revolt, but it is doubtful anyone believed him.

This diplomatic effort did yield some results that inspired false hopes in the Palestinian public. In January 1947, after years of conflict, the British government recognized the Arab Higher Committee (a few months later the committee was also recognized by the United Nations). But the gesture was almost meaningless, since over the following months, hit by a severe winter of austerity and economic crisis, the British government resolved to quit Palestine. The Palestinian leadership tried frenziedly to devise ways of dealing with the imminent power vacuum. The Jewish Agency, by contrast, had been preparing for this juncture since the 1920s. Jamal directed the team that struggled to create a Palestinian state out of nothing to replace the British Mandate. Perhaps he had the necessary qualifications, but he had neither the means nor the time in which to do this.

Nevertheless, he carried out some impressive operations. At his initiative, the Arab Higher Committee set up the Arab Treasury, the supreme financial institution of the national movement. It solicited funds from the Arab world and sought to nationalize the nation’s capital. It was a good replica of the Zionist financial structure, but it was founded too late. The pace of organization had become more dynamic in May 1946, when al-Hajj Amin began to play an active part in these moves. Under al-Hajj Amin’s direction, the committee began to function as a government-in-waiting, with ministries and collective responsibility. The general headquarters was in Cairo and the local headquarters in Jerusalem. Such a structure, which might have suited a European government in exile, only weakened the Palestinians’ ability to act.

49

Al-Hajj Amin was more effective in obtaining and storing arms in various places in the Arab world.

The main burden fell on Jamal, who carried on as best he could. In April 1947, he nationalized the People’s Fund, Istiqlal’s private finance ministry headed by Ahmad Hilmi, a dim personality who would become the prime minister of a symbolic Palestinian government in Gaza at the end of 1948. But Jamal was unable to nationalize Musa al-Alami’s Project for Saving the Land, and the organization of funds and infrastructures faltered.

After intense efforts, in June 1947 Jamal succeeded in unifying the two main youth movements, the Husaynis’

Futuwah

and Nimr Hawari’s

al-Najada

. He placed Mahmud Labib, a retired Egyptian officer, at the head of the unified organization. But in August, Labib carried out a fairly successful operation against Jewish youth in Tel Aviv, and the British authorities expelled him. Hawari also harmed

the common enterprise by reaching an understanding with the Jewish Agency. He then served the Hashemites until 1950 and finally settled down in Israel and became a justice of the peace. But all the operations together could not create a Palestinian fighting body, build a firm financial foundation for taking over the power bases in the country and sustain the diplomatic campaign.

The greatest obstacle on the diplomatic front was that, since February 1947, the British government had adopted the basic Zionist argument that a vast gulf existed between Jewish ‘progress’ and Palestinian ‘backwardness’. In their eyes, this made it impossible, if only on social grounds, to let the Palestinians run the country

–

except under Jewish dominance and outside supervision. In vain Jamal tried to prove to the mandatory government that illiteracy in the Arab population had greatly diminished and that the Palestinians could no longer be described as an ignorant population by comparison with the Jewish community. Had he not been a member of a notable family, and had he been conversant with the ideology and discourse of nationalism, Jamal might have explained to the British government that ‘progress’ and ‘illiteracy’ were irrelevant to the question of who owned the country.

50

Being outside Palestine, al-Hajj Amin probably could not help Jamal to impose his authority. The family

–

that is, the Tahiri branch

–

mistakenly believed that it stood at the center of events. In fact, al-Hajj Amin had to resort to violence to impose his authority and that of his family. Once again, though on a smaller scale, accounts were settled and enemies eliminated in the urban power bases that al-Hajj Amin valued. The murder of Sami Taha, the Palestinian trade unionist, has already been mentioned. Most of the actions were not as violent and consisted mainly of jostling to dominate the national committees. (These bodies ran the local struggle after having made their appearance during the great uprising.) Al-Hajj Amin tried to create new committees to replace them everywhere but succeeded in creating only three, and they did little to stop the Zionist determination to ‘cleanse’ Palestine.

One victim of the account-settling was a member of the family, Fawzi Darwish al-Husayni. Fawzi favored collaborating with the Zionists against the British and had founded a party called

Filastin al-Jadidah

(‘New Palestine’) for this purpose. In his opening speech before a mixed Palestinian and Jewish crowd at the party’s founding, he said:

Experience has shown that the official policy of both sides has brought nothing but harm and suffering to both. The Jews and the Arabs used to live together in amity and cooperation. I myself went along for many years with my cousin Jamal al-Husayni. I took part in the events of 1929, but over the years I realized that this road leads nowhere. The imperialist policy is fooling both of us, Arabs and Jews, and there is no other way but to unite and work shoulder to shoulder for all our sakes.

Fawzi was manipulated by Zionists such as Haim Kalvarisky and by more genuine peace seekers such as the leading members of Brith Shalom. The latter pressured the British police to find Fawzi’s killers

–

believed by everyone, including the police, to be members of his family. The day before he was murdered, Fawzi had made a brave speech attacking Jamal for his uncompromising attitude towards the Jewish community:

They will no doubt incite against us, perhaps even attack us, but if we can demonstrate cooperation with the Jews, useful and productive cooperation, the Arabs will follow us. Because many of those who are following Jamal are doing so from lack of choice.

51

On 10 March 1947, the day Fawzi was killed, the newspaper

al-Wahada

, which favored Jamal, published a strong attack on all who cooperated with ‘the alien invaders who had come to Palestine after 1918’.

52

Fawzi stood out because he had chosen political cooperation with the Jews, but individuals who had personal relations with Jews were not affected. For example, Safwat’s son, Fuad al-Husayni

–

an attractive man with whom many women, Muslim, Christian and Jewish, fell in love

–

had a long affair with a woman who would later become the wife of a prominent Israeli journalist. Their relationship was well known yet did not provoke particular annoyance or censure.

53

These internal dissensions came at the expense of the most important campaign in the history of the Palestinians

–

in the diplomatic arena of the United Nations. The UN had been in existence for two years when it took up the question of Palestine. It was still an inexperienced organization wholly dominated by the United States. In May 1947, it handed the problem to a committee of experts, but unfortunately these experts knew nothing about the subject and some of them were indifferent to it. The UN Special Committee on Palestine (UNSCOP) sat on the issue from May until November and brought forth the Partition Resolution. In 1988, the Palestinians would still regard this resolution as a crime committed by the world against them: partition meant the recognition of a Jewish right to part of Palestine.

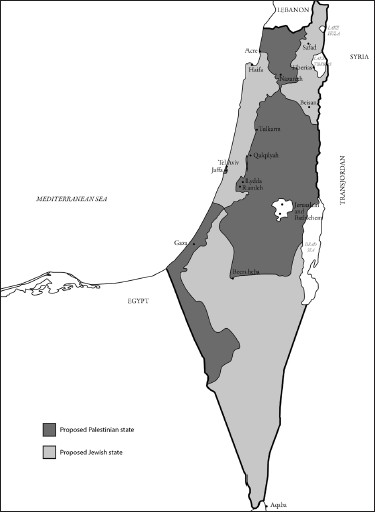

Palestine: United Nations Partition Recommendation, 29 November 1947

Fawzi would have accepted it, perhaps even Musa Kazim, but not Jamal or al-Hajj Amin. Had the Nashashibis been a major political power they might have supported it. But once it was known that Britain was about to quit, they attached themselves to King Abdullah, who thought that dividing the country between himself and the Jews was a good idea. The leadership of the Jewish Agency eagerly

welcomed the proposition, and the absence of a formal agreement between them was due to Ben-Gurion’s territorial aspirations to rule over most of the country, Abdullah’s concern not to seem to betray the pan-Arab interest and the atmosphere of uncertainty before the outbreak of hostilities.

The two sides agreed informally that Abdullah would stay out of the territory of the Jewish state, and in return the Jewish state would let him annex large chunks of Palestine. This was how the West Bank was born, and the Jewish state was spared a direct attack by the Arab world’s best-trained army. Pettiness and religious sensibilities prevented them from agreeing to the partition of Jerusalem

–

which they would do after the war

–

but otherwise their understanding prevailed.

In February 1948, after Bevin’s main advisor on Palestine, Harold Beeley, was sacked, the British government also supported this agreement without reservation and directed the commanders of the Arab Legion to uphold it. The British, the Hashemites and the Zionists all objected strenuously to the establishment of an independent Palestinian state, believing that it would become ‘the

mufti

’s state’. Thus al-Hajj Amin ended up as the

bête noire

of the three most powerful factors in the struggle for Palestine.