The Singularity Is Near: When Humans Transcend Biology (18 page)

Read The Singularity Is Near: When Humans Transcend Biology Online

Authors: Ray Kurzweil

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Fringe Science, #Retail, #Technology, #Amazon.com

Deflation . . . a Bad Thing?

In 1846 we believe there was not a single garment in our country sewed by machinery; in that year the first American patent of a sewing machine was issued. At the present moment thousands are wearing clothes which have been stitched by iron fingers, with a delicacy rivaling that of a Cashmere maiden.

—

S

CIENTIFIC

A

MERICAN

, 1853

As this book is being written, a worry of many mainstream economists on both the political right and the left is deflation. On the face of it, having your money

go further would appear to be a good thing. The economists’ concern is that if consumers can buy what they need and want with fewer dollars, the economy will shrink (as measured in dollars). This ignores, however, the inherently insatiable needs and desires of human consumers. The revenues of the semiconductor industry, which “suffers” 40 to 50 percent deflation per year, have nonetheless grown by 17 percent each year over the past half century.

88

Since the economy is in fact expanding, this theoretical implication of deflation should not cause concern.

The 1990s and early 2000s have seen the most powerful deflationary forces in history, which explains why we are not seeing significant rates of inflation. Yes, it’s true that historically low unemployment, high asset values, economic growth, and other such factors are inflationary, but these factors are offset by the exponential trends in the price-performance of all information-based technologies: computation, memory, communications, biotechnology, miniaturization, and even the overall rate of technical progress. These technologies deeply affect all industries. We are also undergoing massive disintermediation in the channels of distribution through the Web and other new communication technologies, as well as escalating efficiencies in operations and administration.

Since the information industry is becoming increasingly influential in all sectors of the economy, we are seeing the increasing impact of the IT industry’s extraordinary deflation rates. Deflation during the Great Depression in the 1930s was due to a collapse of consumer confidence and a collapse of the money supply. Today’s deflation is a completely different phenomenon, caused by rapidly increasing productivity and the increasing pervasiveness of information in all its forms.

All of the technology trend charts in this chapter represent massive deflation. There are many examples of the impact of these escalating efficiencies. BP Amoco’s cost for finding oil in 2000 was less than one dollar per barrel, down from nearly ten dollars in 1991. Processing an Internet transaction costs a bank one penny, compared to more than one dollar using a teller.

It is important to point out that a key implication of nanotechnology is that it will bring the economics of software to hardware—that is, to physical products. Software prices are deflating even more quickly than those of hardware (see the figure below).

Exponential Software Price-Performance Improvement

89

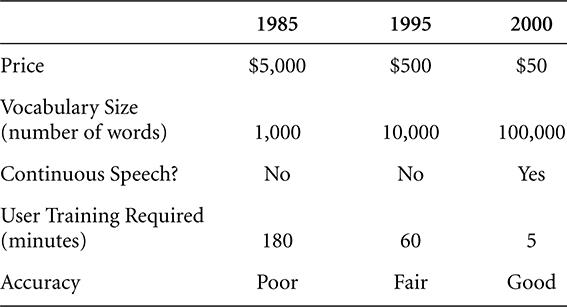

Example: Automatic Speech-Recognition Software

The impact of distributed and intelligent communications has been felt perhaps most intensely in the world of business. Despite dramatic mood swings on Wall Street, the extraordinary values ascribed to so-called e-companies during the 1990s boom era reflected a valid perception: the business models that have sustained businesses for decades are in the early phases of a radical transformation. New models based on direct personalized communication with the customer will transform every industry, resulting in massive disintermediation of the middle layers that have traditionally separated the customer from the ultimate source of products and services. There is, however, a pace to all revolutions, and the investments and stock market valuations in this area expanded way beyond the early phases of this economic S-curve.

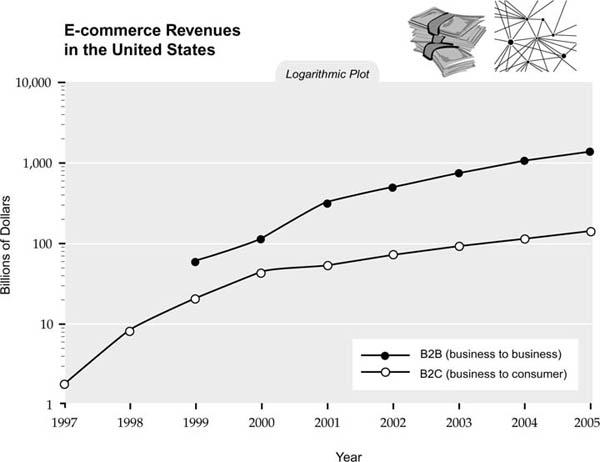

The boom-and-bust cycle in these information technologies was strictly a capital-markets (stock-value) phenomenon. Neither boom nor bust is apparent in the actual business-to-consumer (B2C) and business-to-business (B2B) data (see the figure on the next page). Actual B2C revenues grew smoothly from $1.8 billion in 1997 to $70 billion in 2002. B2B had similarly smooth growth from $56 billion in 1999 to $482 billion in 2002.

90

In 2004 it is approaching $1 trillion. We certainly do not see any evidence of business cycles in the actual price-performance of the underlying technologies, as I discussed extensively above.

Expanding access to knowledge is also changing power relationships. Patients increasingly approach visits to their physician armed with a sophisticated understanding of their medical condition and their options. Consumers of virtually everything from toasters, cars, and homes to banking and insurance are now using automated software agents to quickly identify the right choices with the optimal features and prices. Web services such as eBay are rapidly connecting buyers and sellers in unprecedented ways.

The wishes and desires of customers, often unknown even to themselves, are rapidly becoming the driving force in business relationships. Well-connected clothes shoppers, for example, are not going to be satisfied for much longer with settling for whatever items happen to be left hanging on the rack of their local store. Instead, they will select just the right materials and styles by viewing how many possible combinations look on a three-dimensional image of their own body (based on a detailed body scan), and then having the choices custom-manufactured.

The current disadvantages of Web-based commerce (for example, limitations in the ability to directly interact with products and the frequent frustrations of interacting with inflexible menus and forms instead of human personnel) will gradually dissolve as the trends move robustly in favor of the electronic world.

By the end of this decade, computers will disappear as distinct physical objects, with displays built in our eyeglasses, and electronics woven in our clothing, providing full-immersion visual virtual reality. Thus, “going to a Web site” will mean entering a virtual-reality environment—at least for the visual and auditory senses—where we can directly interact with products and people, both real and simulated. Although the simulated people will not be up to human standards—at least not by 2009—they will be quite satisfactory as sales agents, reservation clerks, and research assistants. Haptic (tactile) interfaces will enable us to touch products and people. It is difficult to identify any lasting advantage of the old brick-and-mortar world that will not ultimately be overcome by the rich interactive interfaces that are soon to come.

These developments will have significant implications for the real-estate industry. The need to congregate workers in offices will gradually diminish. From the experience of my own companies, we are already able to effectively organize geographically disparate teams, something that was far more difficult a decade ago. The full-immersion visual-auditory virtual-reality environments, which will be ubiquitous during the second decade of this century, will hasten the trend toward people living and working wherever they wish. Once we have full-immersion virtual-reality environments incorporating all of the senses, which will be feasible by the late 2020s, there will be no reason to utilize real offices. Real estate will become virtual.

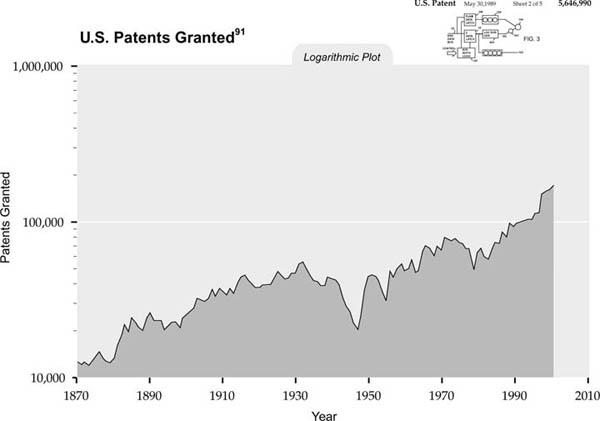

As Sun Tzu pointed out, “knowledge is power,” and another ramification of the law of accelerating returns is the exponential growth of human knowledge, including intellectual property.

None of this means that cycles of recession will disappear immediately. Recently, the country experienced an economic slowdown and technology-sector recession and then a gradual recovery. The economy is still burdened with some of the underlying dynamics that historically have caused cycles of recession: excessive commitments such as overinvestment in capital-intensive projects and the overstocking of inventories. However, because the rapid dissemination of information, sophisticated forms of online procurement, and increasingly transparent markets in all industries have diminished the impact of this cycle, “recessions” are likely to have less direct impact on our standard of living. That appears to have been the case in the minirecession that we experienced in 1991–1993 and was even more evident in the most recent recession in the early 2000s. The underlying long-term growth rate will continue at an exponential rate.

Moreover, innovation and the rate of paradigm shift are not noticeably affected by the minor deviations caused by economic cycles. All of the technologies exhibiting exponential growth shown in the above charts are continuing without losing a beat through recent economic slowdowns. Market acceptance also shows no evidence of boom and bust.

The overall growth of the economy reflects completely new forms and layers of wealth and value that did not previously exist, or at least that did not previously constitute a significant portion of the economy, such as new forms of

nanoparticle-based materials, genetic information, intellectual property, communication portals, Web sites, bandwidth, software, databases, and many other new technology-based categories.

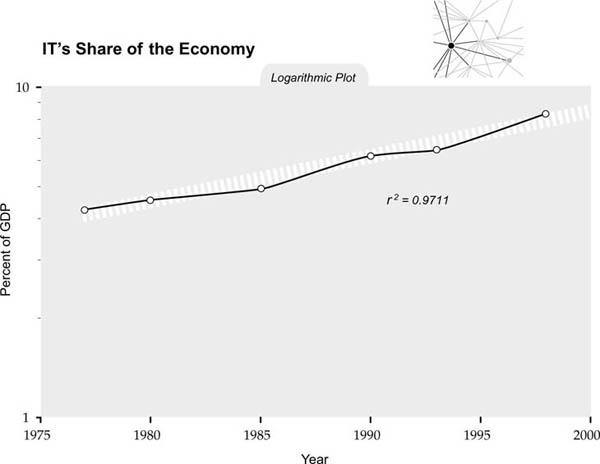

The overall information-technology sector is rapidly increasing its share of the economy and is increasingly influential on all other sectors, as noted in the figure below.

92

Another implication of the law of accelerating returns is exponential growth in education and learning. Over the past 120 years, we have increased our investment in K–12 education (per student and in constant dollars) by a factor of ten. There has been a hundredfold increase in the number of college students. Automation started by amplifying the power of our muscles and in recent times has been amplifying the power of our minds. So for the past two centuries, automation has been eliminating jobs at the bottom of the skill ladder while creating new (and better-paying) jobs at the top of the skill ladder. The ladder has been moving up, and thus we have been exponentially increasing investments in education at all levels (see the figure below).

93