The Spirit Level: Why Greater Equality Makes Societies Stronger (29 page)

Read The Spirit Level: Why Greater Equality Makes Societies Stronger Online

Authors: Richard Wilkinson,Kate Pickett

Tags: #Social Science, #Economics, #General, #Economic Conditions, #Political Science, #Business & Economics

That leaves the question of which way causality goes. Occasionally when we describe our findings people suggest that instead of inequality causing everything else, perhaps it all works the other way round and health and social problems cause bigger income difference. Of course, in the real world these things do not happen in clearly defined steps which would allow us to see which comes first. The limited evidence from studies of changes over time tells us only that they tend to change together. Could it be that people who succumb to health or social problems suffer a loss of income and that tends to increase inequality? Perhaps people who are sick or very overweight are less likely to have jobs or to be given promotion.

Could this explain why countries with worse health and social problems are more unequal?

The short answer is no – or at least, not much. First, it doesn’t explain why societies that do badly on any particular health or social problem tend to do badly on all of them. If they are not all caused at least partly by the same thing, then there would be no reason why countries which, for instance, have high obesity rates should also have high prison populations. Second, some of the health and social problems are unlikely to lead to serious loss of income. Using the UNICEF index we showed that many childhood outcomes were worse in more unequal countries. But low child wellbeing will not have a major influence on income inequality among adults. Nor could higher homicide rates be considered as a major cause of inequality even if the numbers were much higher. Nor for that matter could expanding prison populations lead to wider income differences – rather the reverse, because measures of inequality are usually based on measures of household income which leave out institutionalized populations. Although it could be argued that teenage parents might increase inequality because they are often single and poor, some more equal countries have a high proportion of single parents but a generous welfare system which ensures that a very much smaller proportion of them are in poverty than in more unequal countries. And when the unemployed and the children of single parents are protected from poverty, they are also protected from the human damage it can cause.

However, there is a more fundamental objection to the idea that causality might go from social problems to inequality. Earlier in this chapter we showed that it was people at almost all income levels, not just the poor, who do worse in more unequal societies. Even when you compare groups of people with the same income, you find that those in more unequal societies do worse than those on the same income in more equal societies. Though some more unequal societies have more poor people, most of the relationship with inequality is, as we pointed out earlier, not explained by the poor: the effects are much more widespread. So even if there is some loss of income among those who are sick or affected by some social problem, this does not begin to explain why people who remain on perfectly good incomes still do worse in more unequal societies.

Another alternative approach is to suggest that the real cause is not income distribution but something more like changes in ideology, a shift perhaps to a more individualistic economic philosophy or view of society, such as the so-called ‘neo-liberal’ thinking. Different ideologies will of course affect not only government policies but also decisions taken in economic institutions throughout society. They are one of very many different factors which can affect the scale of income differences. But to say that a change in ideology can affect income distribution is not at all the same as saying that it can also affect all the health and social problems we have discussed – regardless of what happens to income distribution. Although it does look as if neo-liberal policies widened income differences (see Chapter 16) there was no government intention to lower social cohesion or to increase violence, teenage births, obesity, drug abuse and everything else. So while changes in government ideology may sometimes be among the causes of changes in income distribution, this is not part of a package of policies intended to increase the prevalence of social problems. Their increase is, instead, an unintended consequence of the changes in income distribution. Rather than challenging the causal role of inequality in increasing health and social problems, if governments understood the consequences of widening income differences they would be keener to prevent them.

Economists have never suggested that poor health and social problems were the real determinants of income inequality. Instead they have concentrated on the contributions of things like taxes and benefits, international competition, changing technology and the mix of skills needed by industry. None of these is obviously connected to the frequency of health and social problems. In Chapter 16 we shall touch on the factors responsible for major changes in inequality in different countries.

A difficulty in proving causality is that we cannot experimentally reduce the inequalities in half our sample of countries and not in the others and then wait to see what happens. But purely observational research can still produce powerful science – as astronomy shows. There are, however, some experimental studies which do support causality working in the way our argument suggests. Some of them have already been mentioned in earlier chapters. In Chapter 8 on education we described experiments which show how much people’s performance is affected by being categorized as socially inferior. Indian children from lower castes solved mazes just as well as those from higher castes – until their low caste was made known. Experiments in the United States have shown that African-American students (but not white students) do less well when they are told a test is a test of ability than they do on the same test when they are told it is not a test of ability. We also described the famous ‘blue-eyes’ experiments with school children which showed the same processes at work.

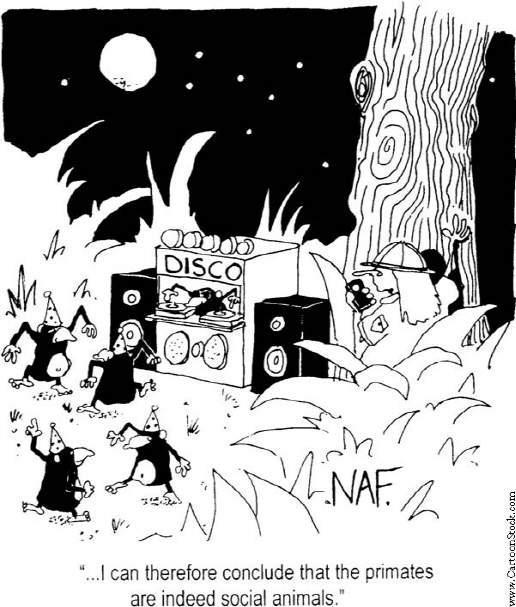

Sometimes associations which are only observed among human beings can be shown to be causal in animal experiments. For instance, studies of civil servants show cardiovascular health declines with declining social status. But how can we tell whether the damage is caused by low social status rather than by poorer material conditions? Experiments with macaque monkeys make the answer clear. Macaques form status hierarchies but with captive colonies it is possible to ensure all animals live in the same material conditions: they are given the same diet and live in the same compounds. In addition, it is possible to manipulate social status by moving animals between groups. If you take low-status animals from different groups and house them together, some have to become high-status. Similarly, if you put high-status animals together some will become low-status. Animals which move down in these conditions have been found to have a rapid build-up of atherosclerosis in their arteries.

322

Similar experiments also suggest a causal relationship between low social status and the accumulation of abdominal fat.

323

In Chapter 5 we mentioned other animal experiments which showed that when cocaine was made available to monkeys in these conditions, it was taken more by low social status animals – as if to offset their lower dopamine activity.

59

Although we know of no experiments confirming the causality of the relation between inequality and violence, we invite anyone to go into a poor part of town and try randomly insulting a few people.

We have discussed the reasons for thinking that these links are causal from a number of different perspectives. But as philosophers of science, such as Sir Karl Popper, have emphasized, an essential element in judging the success of any theory is whether it makes successful predictions. A successful theory is one which predicts the existence of previously unknown phenomena or relationships which can then be verified. The theory that more equal societies were healthier arose from one set of international data. There have now been a very large number of tests (about 200) of that theory in different settings. With the exception of studies which looked at inequality in small local areas, an overwhelming majority of these tests confirmed the theory. Second, if the link is causal it implies that there must be a mechanism. The search for a mechanism led to the discovery that social relationships (as measured by social cohesion, trust, involvement in community life and low levels of violence) are better in more equal societies. This happened at a time when the importance of social relationships to health was beginning to be more widely recognized. Third, the theory that poor health might be one of a range of problems with social gradients related to inequality has been tested (initially on cause-specific death rates as described earlier in this chapter) and has since been amply confirmed in two different settings as we have described in Chapters 4–12. Fourth, at a time when there was no reason to think that inequality had psychosocial effects, the relation between health and equality seemed to imply that inequality must be affecting health through psychosocial processes related to social differentiation. That inequality does have powerful psychosocial effects is now confirmed by its links (shown in earlier chapters) with the quality of social relations and numerous behavioural outcomes.

It is very difficult to see how the enormous variations which exist from one society to another in the level of problems associated with low social status can be explained without accepting that inequality is, in an essential respect, the common denominator, and a hugely damaging force.

Gifts make friends and friends make gifts.

Marshall Sahlins,

Stone Age Economics

LOOKING BEFORE LEAPING

Although attitudes to inequality have always been central to the disagreement between the political right and left, few would not prefer a friendlier society, with less violence, better mental health, more involvement in community life – and so on. Now that we have shown that reducing inequality leads to a very much better society, the main sticking point is whether people believe greater equality is attainable. Our analysis has not of course compared existing societies with impossibly egalitarian imaginary ones: it is not about utopias or the extent of human perfectibility. Everything we have seen comes from comparisons of existing societies, and those societies have not been particularly unusual or odd ones. Instead, we have looked exclusively at differences between the world’s richest and most successful economies, all of which enjoy democratic institutions and freedom of speech. There can be no doubt whatsoever that human beings are capable of living well in societies with inequalities as small – for instance – as Japan and the Nordic countries. Far from being impractical, the implications of our findings are probably more consistent with the institutional structures of market democracy than some people – at either end of the political spectrum – would like to believe.

Some may still feel hesitant to take the evidence at face value.

From the vantage point of more unequal countries, it may seem genuinely perplexing and difficult to understand how some, apparently similar, countries can function with so much less inequality. Evidence that material self-interest is the governing principle of human life seems to be everywhere. The efficiency of the market economy seems to prove that greed and avarice are, as economic theory assumes, the overriding human motivations. Even the burden of crime appears to spring from the difficulty of stopping people breaking the rules to satisfy selfish desires. Signs of a caring, sharing, human nature seem thin on the ground.

Some of this scepticism might be allayed by a more fundamental understanding of how we, as human beings, are damaged by inequality and have the capacity for something else. We need to understand how, without genetically re-engineering ourselves, greater equality allows a more sociable human nature to emerge.

TWO SIDES OF THE COIN

In our research for this book, social status and friendship have kept cropping up together, linked inextricably as a pair of opposites. First, they are linked as determinants of the health of each individual. As we saw in Chapter 6, friendship and involvement in social life are highly protective of good health, while low social status, or bigger status differences and more inequality, are harmful. Second, the two are again linked as they vary in societies. We saw in Chapter 4 that as inequality increases, sociability as measured by the strength of community life, how much people trust each other, and the frequency of violence, declines. They crop up together for a third time in people’s tendency to choose friends from among their near equals: larger differences in status or wealth create a social gulf between people.