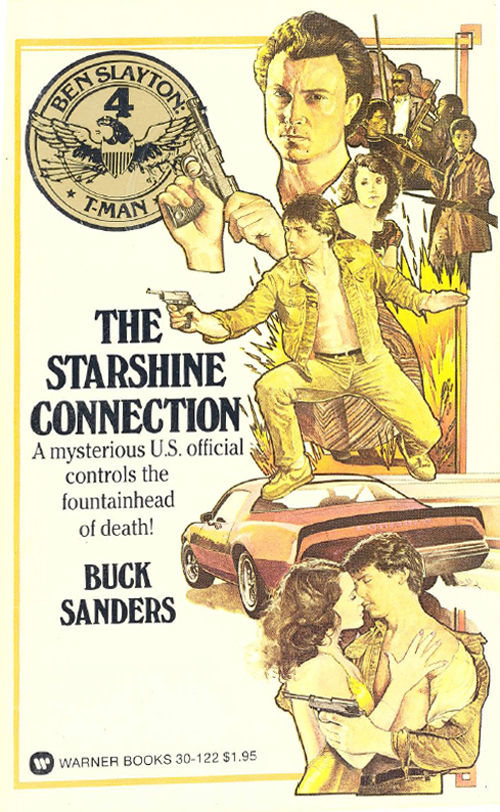

The Starshine Connection

Read The Starshine Connection Online

Authors: Buck Sanders

Alone, somewhere in Mexico, and about to be killed by bribed Federales. Incapable of defending himself, doped up and bound

like a chicken ready for the chopping block. They tossed him into a cell and the Federales began softening him up the way

a cook might soften a cheap steak with a tenderizing mallet. What had he done wrong? He had to make his phone call, had to

call Winship in Washington and find out what he had done wrong! Did he have Miranda rights in Mexico? Did Mexico have an repatriation

treaty with the United States? Did they even have

phones

in Mexico…?

T-Man #1: A Clear and Present Danger

T-Man #2: Star of Egypt

T-Man #3: Trail of the Twisted Cross

T-Man #4: The Starshine Connection

Published by

WARNER BOOKS

WARNER BOOKS EDITION

Copyright © 1982 by Warner Books, Inc.

All rights reserved.

Warner Books, Inc.

Hachette Book Group

237 Park Avenue

New York, NY 10017

Visit our website at

www.HachetteBookGroup.com

First eBook Edition: September 2009

ISBN: 978-0-446-56615-5

Contents

Ben Slayton Realized that no One knew where he was.

“Códmo te gusta, gabacho?”

The question was a crude joke, accompanying as it did the man’s headlong plunge onto the floor.

The floor was closely packed dirt. Brown and choking, it kicked up a pale cloud of dust as the man made contact with it, propelled

there by the

Federale

who had escorted him to the cell.

The scene was so clichéd in the prisoner’s mind as to be nearly surreal. It was a Mexican jail with adobe walls and a dirt

floor. The

Federale

had a lewdly crooked mustache, a gold tooth right in front, black beard-stubble to beat the band, and a huge beer belly straining

against the confines of his sweat-soaked tan uniform. He also had the strength of a practiced sadist, grabbing the prisoner

by the crotch of his pants and the scruff of his neck and introducing him to his cell with a grunt and a fling.

The prisoner clopped across the cell on rubbery legs. He met the far wall with a crunch, rebounded drunkenly, lost his balance,

and sprawled on the ground. The guard watched, allowing himself his own brand of disgust. The man clawed at the floor, trying

to hang onto it in the mistaken impression he could hold his own swirling world still. His legs flailed, uncontrolled by his

mind. Sweat poured from him as from a fever victim.

Fuentes, the guard, knew the man was not sick. He was

dndrogada,

drugged to the gills—though on what, Fuentes had no idea, and cared less. More to the point, Fuentes was a class-A Mexican

bigot. He despised Chicanos and their pathetic attempts to mate their character with American sensibilities. To him, such

coupling was like trying to hybridize a snake with an eagle—the result would be no good for anything except making true Mexicans

throw up in disgust. This less-than-brotherly sentiment on behalf of Chicanos made Fuentes’s attitude toward Americans famous

in his district. That they were all whores or sons of whores was a forgone conclusion.

It had taken the man on the floor of the cell about ninety seconds to climb to his hands and knees. Fuentes cleared a stray

hair of his

mostacho

away from his mouth, stepped forward, and with a practiced motion, swung his booted foot upward into the man’s stomach. He

flipped over without a noise, landing on his head, and splaying across the floor. He had a mouthful of loose dirt, but barely

enough saliva to make it into mud inside his mouth.

Behind Fuentes, another passing guard arched his eyebrows in silent question as to the problem of the

gringo

in their smallest cell. Fuentes said nothing.

His companion, Cholla, squinted briefly -at the white man, mumbled,

“Quedarse súpito,”

almost inaudibly, and left. Fuentes nodded. The

gringo

was completely under.

To Fuentes, it was not enough to hate Americans merely for their drug trafficking, their annoying melting-pot approach—lumping

the Spanish in with the Mexicans and assuming they were the same, for example—or their snobbish disdain for Mexican culture.

He had formulated his hatred from observing wave after wave of plump American

touristas

and their chicken-skinned

puta

wives and their

melenudo

children. As to this last, Fuentes had taken great joy in rounding up long-haired Mexican boys once the law had been passed.

Grabbed them straight off the. street and trooped them to the barber in bunches for a proper shearing. Fuentes himself had

wide, white sidewalls around each ear, and hair no longer than half an inch on top. He respected the decrees of the

Nacionales.

Then he found out that the reason the law had been passed in the first place was so

touristas

would not be offended by the scruffy appearance of long-haired kids in the streets during their trips across the border.

It was all a show for the

gringos,

the

gabachos.

That was another strike the man on the floor had against him: not only was he an American, not only was he drugged, or drunk,

not only was he an irresponsible mess, but as far as Fuentes was concerned, he was a

jipi,

a hippie, judging by his rags and his unkempt hair. As such, he was, for Fuentes, the perfect embodiment of every wrong ever

wrought on the Mexican culture and character by Americans. And Fuentes never let opportunity get away from him when it favored

his prejudices so blatantly.

He gave the unconscious man a swift boot in the ribs. The man groaned and withdrew, like a snail, into a more fetal, protected

position. Fuentes grinned and kicked the man again. This time, no reaction.

He frowned suddenly and bent to check the man’s jugular pulse, holding two fingers skillfully against his throat. He was still

alive, his breath coming in shallow gasps, his perspiration a living thing standing out in beads against the dim light in

the close and stinking cell. He was still alive, but not conscious.

Fuentes lit a sulphur match by snapping it against his thumbnail, a trick learned early in life on the streets. He lifted

the insensate man’s left hand by the wrist, so it dangled limply in the air. Between his fingers he could also feel a weak

but regular pulse, assuring him that there was nothing wrong with this

fundillo

that a rigorous sobering-up program would not cure—so Fuentes proceeded with his own peculiar brand of sobering-up.

He held the match below the man’s hand and watched it redden, then scorch, the flesh of the palm. Finally, there was a reaction.

The man cried out weakly, like a girl or a baby. Fuentes vised the wrist and flipped the man over again. He stood to his full

height and planted his boot on the man’s throat as he struggled for breath.

He had America by the throat.

Gringos bastardos!

But the man was not even capable of a good fight, let alone a token resistance. Fuentes decided to return when he could force

the man to stand up, so he could flatten him with a few well-placed punches. Harassing officers of the law, taunting his jailers;

yes, that would be a good one. You could insult the idiots to South America and back and they never understood a word you

were saying. Because they, like all Americans, were overconfident and stupid.

He had returned to the door of the cell when the man on the floor spoke to him.

The voice was a dry growl of defiance.

“Tiene lonjas mas grandes, eh, gordinfldn?”

Insults! Fuentes reddened. Insults from the

hijo de puta

on the floor, the American sonofabitch he had thought unconscious! He was faking it!

With a smile of pure pleasure, Fuentes slammed the cell door, remaining on the inside. He hitched up his belt, and then waded

into the man on the floor.

Cholla passed by the cell again, peering briefly through the slot in the door. Fuentes was doing his dance, kicking the shit

out of the

gringo

in the cell. He shrugged to himself. It was a slow Wednesday.

Benjamin Justin Slayton, special assignment pet of Hamilton Winship of the United States Treasury Department and number-one

troubleshooter for the difficulties of said office, was whacked out of his skull.

They had poured liquor down his levered-open gullet. They had injected kickapoo-juice into his bloodstream. They had blindfolded

him, let the intoxicants get a running start, and then they had passed him around like the last roach at a pot party, pounding

and pummeling the piss out of him. Three, four, or two hundred: it made no difference to him then—it might as well have been

a legion of Cortez’s in full armor and regalia that had run him through the meat grinder. Ben Slayton was signed, sealed,

and delivered. And he didn’t even care, let alone know, where in hell he had been delivered to.

The colors, the flowing shapes, undulating and geometric, were the first order of attention. There was much to be learned

from observing, with a scholarly eye, the ebb and flow of rainbow trapezoids and long funnelling corridors of purple and ebony.

Ben Slayton was whacked out of his skull, and not doing a damn thing about it except grooving on the colors. He was actually

capable of little else.

You are the sunshine of my… no wait, starshine of my leaf. My left. No, wait a minute…

He began to sing it in the car as they drove. The singing, he reasoned, would serve a twofold purpose. It would put his captors

at ease, thinking he was stoned. He would sing loud and long in his rich basso, and in so doing hide the fact that the bumpy

car ride had aroused him sexually—nothing more embarrassing than an erection in a carload of

cholos

—and it would prove that he was still conscious, still lucid: indeed, still capable of putting out the words to something

as complex as a song without mucking it up! Try to dope him up and run a fast one past Ben Slayton? Hah! Cold day in hell.

Singing would also refute the allegation of someone else in the automobile that Slayton was knocked out. Dumb Chicanos. They

thought he did not understand their insults, their conversation, their plotting as to where he would be taken and what would

be done with him. He was a goddam Treasury agent; they couldn’t get away with this!

He opened his mouth to sing and somebody slapped it shut. So much for that brilliant idea.

The blow stung him back to momentary reality. These bastards were taking him to be killed!

Training,

his mind chattered,

training and discipline! You’ve been bombed before! Burn it off, bring yourself out of it, they’re going to kill you, you

dumb gringo, they said so!

Or was it

have you

killed? He furrowed his brow. He could not remember. That was the problem with the grammar in romance languages, he complained

to himself; declaratives and inquisitives all sounded alike when they were slurred. Or was it declaratives and imperatives?

Slayton was confused. But it was okay to be confused in Mexico; Mexico was a place where confusion was the order of the day,

n’cest-ce pas?

Something seemed wrong with that, too.

Damn it, nothing was staying the same for more than a few seconds! How in hell could he be expected to behave professionally

when reality stayed in flux, kept zipping around like a crazy slot car on a chicane track, always changing lanes unexpectedly?

He thought he could fool them by pretending to be blasted—that was the key! If they

thought

he was stoned, he would be no threat to them, and he could make his plans and escape unnoticed.

Slayton promptly pounded the shoulder of the

cholo

beside him in the back seat. He pounded with his head, using a butting motion to get the boy’s attention—his hands were bound

behind him and the rough hemp chafed his wrists. Slyly, he told the man that he would fool them by pretending to be childlike,

by

faux-naif,

eh?

The boy’s eyes flared whitely in the nut-brown face. “

Callaté, gabacho!”

He slammed a pointed elbow into Slayton’s ribs and Slayton folded up as much as his bindings would permit. He was wound up

inside coil after coil of thick shipping rope. His nose was in terrible pain.