The Sugar King of Havana (32 page)

Read The Sugar King of Havana Online

Authors: John Paul Rathbone

MILTON HERSHEY, the chocolate maker, was the soft-spoken son of a Mennonite family, an Anabaptist sect similar to the Amish. His Cuban property, founded in 1916 to supply Hershey’s growing American chocolate empire, consisted of three sugar mills, a refinery, and fifty thousand acres of choice real estate about a half-hour drive outside Havana. It was established along the same lines as Hersheyville, the utopian factory town he built outside Philadelphia, with subsidized houses equipped with electricity and running water for the workers. Hershey’s own house was an elegant hacienda, with private rooms that opened on three sides to sweeping views of the Caribbean, the cane fields, and the refinery. Hershey spent most of his later years living on the estate, plagued by insomnia, grieving the death of his beloved wife, Kitty, whiling away the hours scraping liver spots from the back of his hands with a penknife and treating the wounds with cocoa butter.

Lobo had first stalked the property in the mid-fifties when he tried to take over Cuban Atlantic, the sugar company that had bought Hershey’s mills in 1946 shortly after the old man died. Czarnikow-Rionda, getting wind of Lobo’s interest, tried to stall their competitor by leaking a spoiler to the press. The article that appeared in the

Journal of Commerce

on February 3, 1956, claimed that if Lobo’s bid was successful he would control as much as half of Cuba’s sugar production. Lobo could then say to U.S. refiners, “Pay me my price for your sugar, or else.” This was indeed theoretically possible, due to the small size of “freefloat” sugar then actively traded. Most of the 50 million tons the world produced each year was consumed in protected home markets. Cuba, producing 5 million to 6 million tons, was the largest single exporter and accounted for as much as half the freely traded market. Anyone who controlled Cuban sugar could therefore control the world market. The Cuban Atlantic deal, the article suggested, would be a classic Lobo market squeeze, only on a global scale.

Journal of Commerce

on February 3, 1956, claimed that if Lobo’s bid was successful he would control as much as half of Cuba’s sugar production. Lobo could then say to U.S. refiners, “Pay me my price for your sugar, or else.” This was indeed theoretically possible, due to the small size of “freefloat” sugar then actively traded. Most of the 50 million tons the world produced each year was consumed in protected home markets. Cuba, producing 5 million to 6 million tons, was the largest single exporter and accounted for as much as half the freely traded market. Anyone who controlled Cuban sugar could therefore control the world market. The Cuban Atlantic deal, the article suggested, would be a classic Lobo market squeeze, only on a global scale.

From New York, the day after the article appeared, Czarnikow-Rionda warned Havana about possible repercussions. “Lobo’s office has admitted to us that their organization is quite upset and [Lobo] is naturally quite wild,” the cable read. “This is probably the first round.” It was. Ten days later, Lobo moved on Cuban Atlantic in the same way he had tried to take over Cuba Company ten years before. He bought 300,000 of the firm’s shares on the open New York market, a 15 percent stake, and planned to gain other allies and so take over the rest at a shareholders’ meeting in March.

It was a daring raid. Hostile takeovers were still rare then, although Lobo was more or less infamous for them. Hostile takeovers funded by debt were rarer still; they would become commonplace in the United States only in the mid-1980s, with the rise of Michael Milken, the junk bond king. Lobo was therefore ahead of the financial curve. Politically, though, he had miscalculated. Laurence Crosby, Cuban Atlantic’s chairman, was close to Batista, who could be persuaded to oppose the deal. Crosby could also count on Lobo’s old adversary Francisco Blanco to cast his 100,000 shares alongside the company’s incumbent managers. Meanwhile two North American investors, the Bronfman family, which owned the Seagram distillery, and the Wall Street banker John Loeb, teamed up with Cuba’s largest sugar concern, the Falla-Gutiérrez trust, and bought 25 percent of the company. Blocked and unable to gain control, Lobo backed out, sold his stake to Loeb, and watched with dismay as Blanco was elected to the board.

Still, Lobo made a handsome profit. Cuban Atlantic’s share price had almost doubled to $14 during the battle, and Lobo pocketed some $2.5 million from the increase. His life offered other compensations too. One month after retiring from the battle, Lobo married again, this time to a mysterious international glamour girl who had the looks of a Valkyrie, Hilda Krueger.

A FULL-BODIED BLONDE with wide lips, high cheekbones, and a figure that stopped traffic, Krueger had first met Lobo in Havana eleven years earlier, while he was still married to María Esperanza. Krueger had come to Havana to give a lecture about La Malinche, the Native American mistress of Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés, and to interview then-president Grau for a Mexican newspaper. Krueger telephoned Lobo in Havana after one of María Esperanza’s cousins arranged the introduction. Out of courtesy, Lobo met Krueger for a drink at the Nacional. It was her birthday, and they celebrated. Lobo had been unable to forget Krueger ever since—notwithstanding his subsequent affairs with Fontaine, Varvara, and others. It was to Krueger that Lobo had stopped to send a love note while rushing home the evening he was shot.

Born in Cologne in 1912, Krueger is an intriguing character, more survivor than free spirit. She made her name in prewar Germany as a minor film star. An American diplomat described her then as “one of those bevy of girls that were called upon occasionally to furnish a little ‘joy thru strength’ to the Hitler-Goebbels combination by a night of frolicking à la Nero.” In Berlin, Krueger also knew Jean Paul Getty, the American industrialist and a known Nazi sympathizer. When she emigrated to the United States after war broke out, FBI agents trailed her because of their supposed love affair.

The FBI gamely referred to Krueger as “Hitler’s lover” and suspected her of being a spy. In New York, they tapped her phone calls and read every telegram sent or received, and most of her mail. In Los Angeles, one agent reported that he found a heavily marked-up biography of Mata Hari in her bags. Blackballed, Krueger was unable to find work in wartime Hollywood and so moved to Mexico, Getty arranging the visa. There she took up with Miguel Alemán, Mexico’s minister of the interior, although Getty did not seem to mind the slight. He gave Krueger $5,000 to finance her film activities and asked her to marry him, saying that “he didn’t care about his wife” and “couldn’t wait to get a divorce to marry again.” Krueger declined, finding Getty too prudish, too concerned about others’ opinions, and having “a very feminine attitude.” Soon after, she and Lobo became lovers. She moved to Havana and eventually issued an ultimatum that he marry her. Lobo agonized over the decision for months. Jealous and suspicious, he even hired private detectives to trail Krueger when she traveled abroad.

They eventually wed in a small civil ceremony on April 9, 1956, and Mrs. Hilda K. de Lobo began to make a new life for herself in Havana. For a while her name appeared in the slim blue book that Lobo used to note down menus and placements for dinners held at the house on Eleventh and Fourth streets. She sat at the head of the table facing Lobo on July 24, again on January 8 the following year, and on January 22, two weeks later. Then Krueger’s name suddenly dropped away, and Lobo’s sister Helena sat again opposite her brother at the head of the table.

Separation had been only a matter of time. It was impossible for Krueger to build an independent life in Cuba. Tight-knit Havana society circled its wagons around María Esperanza, who had remarried to Manuel Ángel González del Valle, a well-connected real estate developer. Lobo meanwhile pursued his ventures, including a large real estate deal with the U.S. real estate tycoon Bill Zeckendorf. Amid such wheeling and dealing there was little room in his life for Krueger. “Hilda was very beautiful, very alive,” remembered León. “In Havana she wanted to go out for dinner, to go to the Tropicana. All Julio wanted to do was go to his mills. That wasn’t the life for a woman like Hilda. The marriage ended—because she got bored.” Lobo saw it much the same way. “Yes it was a busy and interesting life,” he later reflected with regret. “My emotional life with my two wives took a backseat, and there are times when chasing the things money can buy, one can lose sight of those things which money can’t buy and are usually free.”

Krueger left Havana in March 1957, less than a year after the wedding. She was relieved to be out of an increasingly unsettled country that reminded her of the Germany she had escaped two decades before. In December, Castro had landed in Cuba on the

Granma

; Lobo was eating dinner at home on the terrace when he took the call from Pilón’s manager to tell him that there had been fighting around his mill. Furthermore, a few days before Krueger left, the Revolutionary Directorate had assaulted the Presidential Palace. Krueger also left $1 million richer, thanks to the prenuptial settlement she had insisted on. (In Copenhagen, Varvara’s ambitious mother was furious. “You idiot,” she told her daughter. “You should have done the same.” Varvara was nonplussed.) Still, if Krueger had dug Lobo for a million, he nurtured no resentment. The separation was mutual; they remained friends for life, and less than six months after the divorce they lunched at the Sherry-Netherland in New York. The news of the day was the successful Russian launch of Sputnik, the first satellite in space. Lobo turned to León, also there, and asked in jest, “Enrique, do you think with all these technological advances my engagement ring to Krueger might become worthless as they will soon be making artificial diamonds just as big?”

Granma

; Lobo was eating dinner at home on the terrace when he took the call from Pilón’s manager to tell him that there had been fighting around his mill. Furthermore, a few days before Krueger left, the Revolutionary Directorate had assaulted the Presidential Palace. Krueger also left $1 million richer, thanks to the prenuptial settlement she had insisted on. (In Copenhagen, Varvara’s ambitious mother was furious. “You idiot,” she told her daughter. “You should have done the same.” Varvara was nonplussed.) Still, if Krueger had dug Lobo for a million, he nurtured no resentment. The separation was mutual; they remained friends for life, and less than six months after the divorce they lunched at the Sherry-Netherland in New York. The news of the day was the successful Russian launch of Sputnik, the first satellite in space. Lobo turned to León, also there, and asked in jest, “Enrique, do you think with all these technological advances my engagement ring to Krueger might become worthless as they will soon be making artificial diamonds just as big?”

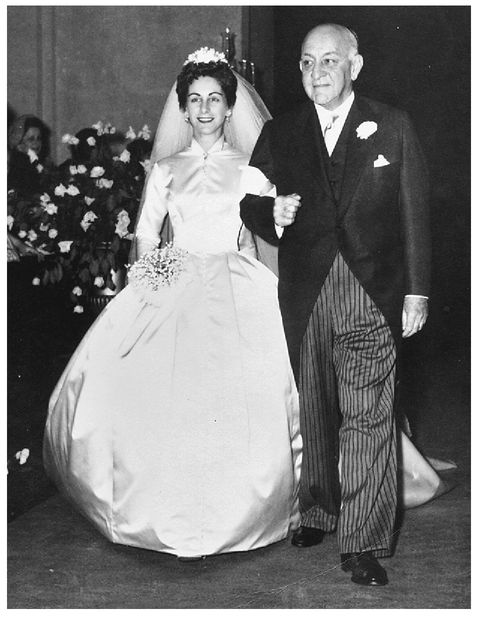

Leonor on her father’s arm. Havana, December 1957.

“No,” interjected Krueger in her German-accented English. “Because before that happens I will already have sold.”

Even Lobo’s market timing was rarely this good. As he wrote to Varvara the following year, “Most people do the wrong thing at the right time or the right thing at the wrong time.” And, in Lobo’s case, sometimes both.

BACK IN HAVANA, Lobo’s thoughts returned to Hershey. This time he found Loeb a keen seller. A gaunt financier with an owlish face who had wintered in Cuba with his wife for three decades, Loeb was worried by the country’s instability. He was also mindful of the heady international context. Revolution was sweeping Africa and Asia, and new nations were forging independence from French, British, and Belgian colonial rule. Keen to sell his Cuban investments, Loeb had even found a possible buyer—a close Batista associate named Pedro Grau. An odd man, no relation to the former president, Grau was a real estate developer with an interest in cryogenics, who wanted to build a nuclear station at Hershey that would power Havana’s industrial park and supply Miami’s energy needs too. But Grau lacked funding for this ambitious plan, and when Loeb began to persuade Lobo to come in, he fell away from the deal.

Lobo, once so keen to buy, now dragged his feet. Loeb insisted: “Julio, you either buy it before the end of the year or you are not going to get it.” Like Loeb, Lobo was concerned by the situation. In May, a fire—suspected to have been caused by a bomb—had brought Tinguaro to a halt eight days before the end of the grinding season. Castro’s 26 July movement was also extending its reach into the cities. It had even warned Lobo of a bomb that would be placed at Leonor’s forthcoming wedding. As a

boda del gran mundo

, due to be held at the Cathedral, government officials would have been socially bound to come. Leonor’s marriage to Jorge González, a Spaniard, was instead moved to a small chapel in Vedado and the ceremony was delayed until December, María Luisa having eloped with John Ryan, an American, and wed in London the year before.

boda del gran mundo

, due to be held at the Cathedral, government officials would have been socially bound to come. Leonor’s marriage to Jorge González, a Spaniard, was instead moved to a small chapel in Vedado and the ceremony was delayed until December, María Luisa having eloped with John Ryan, an American, and wed in London the year before.

Yet despite these warning signals—or perhaps because of them—Hershey still enticed Lobo. His motivations were complex. Lobo was now fighting his own war against the president. He had edged Batista out of the shipping firm Naviera Vacuba, one of Cuba’s largest, by swapping the company’s debts, which his bank controlled, for Batista’s equity stake. Buying Hershey would be another step in this battle, albeit a larger one. Furthermore, this time Blanco would be unable to summon Batista’s protection, as the president now spent most of his time holed up at his farm Kuquine, surrounded by barbed wire and armed guards, compulsively reading the transcripts of phone taps he had placed on his growing list of enemies. Whatever might happen next in Cuba, Lobo also calculated he could make back his investment in three years. Such a rapid return made for an apparently safe buffer.

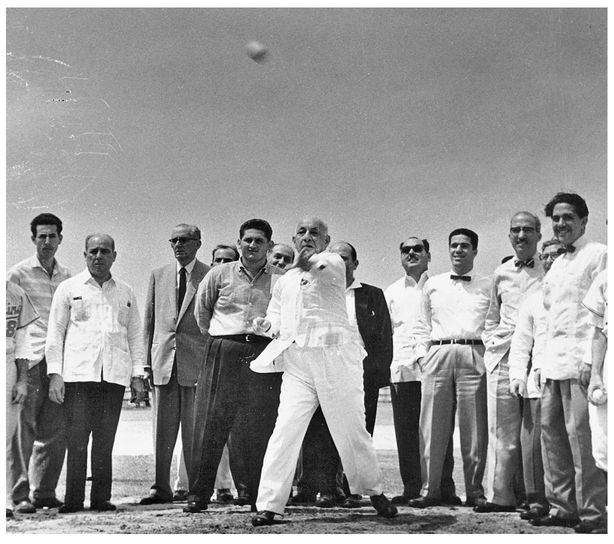

Lobo throws the first ball at an amateur baseball game on the Hershey property.

He bought the mill at midnight, New Year’s Eve, 1957.

He bought the mill at midnight, New Year’s Eve, 1957.

Other books

The Golden Fleece and the Heroes Who Lived Before Achilles by Padraic Colum

Best Australian Short Stories by Douglas Stewart, Beatrice Davis

Finding Father Christmas by Robin Jones Gunn

La nave fantasma by Diane Carey

The Eye of Midnight by Andrew Brumbach

Awakening by Hayes, Olivia

Where Serpents Sleep by C. S. Harris

Wolves of the Beyond: Shadow Wolf by Kathryn Lasky

Payback Is a Mutha by Wahida Clark

Reason to Wed (The Distinguished Rogues Book 7) by Heather Boyd