The Sugar King of Havana (28 page)

Read The Sugar King of Havana Online

Authors: John Paul Rathbone

“Was it possible for the spirits of the young people present to give themselves over to pastimes other than those suggested by the pleasing objects before them? No, it was impossible.” The question is asked and answered by Cuba’s first novelist, Cirilo Villaverde, during a description of a Havana ball in 1830. More than a century later, the glittering young things of Cuban society still did what they had always done: the right thing, with the right people, at the right time, and in the right places, be that the Country Club and the Yacht Club for the Christmas and New Year parties, lunches in Havana at the Floridita, or summer sojourns at Varadero or a

finca

like Lobo’s. It seems frivolous now only because of what happened later. But at the time, if the Hollywood stars who visited Cuba so often did the same, emulating their life, who could gainsay them?

finca

like Lobo’s. It seems frivolous now only because of what happened later. But at the time, if the Hollywood stars who visited Cuba so often did the same, emulating their life, who could gainsay them?

LOBO’S PARTIES AT TINGUARO, however much fun, or his affairs, however gallant, were still diversions from his work life. Indeed, while Lobo was courting Fontaine, the largest sugar harvest in Cuban history was being reaped. Its size was due to good weather and large cane sowings during the first days of the Korean War. The bumper 1952 crop promised an island-wide bonanza. Yet as before, many also worried that the surfeit of Cuban sugar would depress world prices. Just as Machado’s government had done twenty years before, Batista’s government stepped into the breach. In an attempt to keep prices high, it decided to keep back 1.8 million tons in reserve and restrict Cuba’s next harvest as well.

The plan was vigorously attacked by Lobo, among others. For the traders, Havana broker Lamborn & Co. wrote in July 1952: “Restriction is not the only or best response in a world of growing population and expanding markets. . . . The effects could be felt for years.” As for the producers, Alejandro Suero Falla, the president of Cuba’s second-largest sugar company, wrote that August: “The Cuban people should not accept the resolution, as it will affect the whole economy, today and tomorrow.” Such men’s reasons were long familiar. If Cuba restricted its harvest, other producers would simply increase theirs. The world price would still fall, only Cuba would suffer most and the island would repeat the same mistake it had made during the Great Depression, when the Chadbourne Plan that Lobo had criticized so fiercely had failed, as would this one.

Lobo, now a major planter in his own right, had a different vision of Cuban sugar. He envisaged a modernized industry that used tractors and trucks instead of cane-laden oxcarts, each year grinding out an outsized crop of low-cost sugar that it would then slap onto the market. Although prices might fall, Lobo believed higher volumes would compensate. Cuba, uniquely well suited to growing sugarcane, would then emerge victorious from the ensuing price war, and dominate the world market as never before. Instead Cuba had retreated and the opposite had happened. The Cuban crop had barely increased over the past twenty-five years, and no new mills had been built since 1928. Meanwhile, world consumption had doubled. To Lobo, this meant that upstart nations with modern methods had taken a bigger and bigger piece of the fast-growing pie. Worse, Cuba had let them do it.

Lobo knew that to achieve his ideas would require a complete sea change in Cuban attitudes. One third of the Cuban labor force was directly employed in sugar, and their pay was linked to what was known as the annual average price of sugar, or

promedio

. If the

promedio

was low, everyone earned less. Lobo’s emphasis on the volume of the harvest rather than its price therefore threatened everyone, from the man with a machete to the man with a mill. That was why Eusebio Mujal, head of the Cuban Trade Union Federation, called Lobo Cuba’s public enemy number one. Cuba’s sixty thousand small sugar farmers, called

colonos

, felt much the same. And at official levels, opposition to the kind of mechanization Lobo proposed was such that when he imported an experimental cane-cutting machine, it remained in a customs warehouse for five years and was eventually returned to Louisiana after the authorities refused it entry.

promedio

. If the

promedio

was low, everyone earned less. Lobo’s emphasis on the volume of the harvest rather than its price therefore threatened everyone, from the man with a machete to the man with a mill. That was why Eusebio Mujal, head of the Cuban Trade Union Federation, called Lobo Cuba’s public enemy number one. Cuba’s sixty thousand small sugar farmers, called

colonos

, felt much the same. And at official levels, opposition to the kind of mechanization Lobo proposed was such that when he imported an experimental cane-cutting machine, it remained in a customs warehouse for five years and was eventually returned to Louisiana after the authorities refused it entry.

The country was in a bind. In 1955, the National Bank warned that Cuba needed to produce more sugar—seven million tons—if it wanted to maintain living standards from ten years ago. Cubans were therefore doomed if they embraced Lobo’s suggestions, and doomed if they didn’t. Diversification away from sugar was one alternative, and Cubans might have been happy to see the sugar industry modernized if displaced workers could get jobs elsewhere. Unfortunately, such jobs did not exist. Meanwhile the industry was governed by labor laws that had been necessary and humane in the 1930s, but twenty years later had boxed it into a corner. International quotas also restricted some foreign markets. The system had reached its limits and was only rescued when prices rose thanks to unpredictable circumstances elsewhere, such as the Korean War or the Suez crisis. This, though, was a lottery.

Lobo continued to cajole and protest. “One has to modernize or disappear,” he argued. Yet no government, neither Grau’s nor Prío’s before, nor Batista’s afterward, was prepared to defy the political power of the sugar laborers or the

colonos

. And it was the Cuban state that ultimately ran the industry, not the mill owners. Sometimes that even meant abetting speculation on international markets. This was the seamier underside of ostensibly enlightened government involvement that Heriberto had seen firsthand twenty years before when Colonel Tarafa had asked him for advice on a speculative position. In fact, it was now thought that one reason for Batista’s restrictions was again to profit a speculator close to the president.

colonos

. And it was the Cuban state that ultimately ran the industry, not the mill owners. Sometimes that even meant abetting speculation on international markets. This was the seamier underside of ostensibly enlightened government involvement that Heriberto had seen firsthand twenty years before when Colonel Tarafa had asked him for advice on a speculative position. In fact, it was now thought that one reason for Batista’s restrictions was again to profit a speculator close to the president.

The magazine

Bohemia

revealed an interesting detail about Batista’s sugar policy that related to Francisco Blanco, Lobo’s longtime adversary. Born in Oriente, Blanco was a well-known speculator and capable

hacendado

who maintained good political connections. He had been close to Prío, who years before had allegedly bailed Blanco out of a losing short position when the sugar price was rising. To stave off his potential ruin, the government had rescued Blanco by selling him 815,000 tons of sugar on the cheap from its own reserves so that he could close his position without bankrupting other Havana sugar brokers, counterparties to the trade. When Prío went into exile after the 1952 coup, Blanco cozied up to Batista.

Bohemia

revealed an interesting detail about Batista’s sugar policy that related to Francisco Blanco, Lobo’s longtime adversary. Born in Oriente, Blanco was a well-known speculator and capable

hacendado

who maintained good political connections. He had been close to Prío, who years before had allegedly bailed Blanco out of a losing short position when the sugar price was rising. To stave off his potential ruin, the government had rescued Blanco by selling him 815,000 tons of sugar on the cheap from its own reserves so that he could close his position without bankrupting other Havana sugar brokers, counterparties to the trade. When Prío went into exile after the 1952 coup, Blanco cozied up to Batista.

How interesting,

Bohemia

pointed out in an article, that Blanco, whose nephew managed Batista’s sugar mill Washington, had paid $24 million to Dr. Jorge Barroso, head of the Sugar Board. How interesting too that almost every morning Blanco visited Amadeo López Castro, the government’s representative at the committee on sugar sales. Was it as a result of this, perhaps, that a Cuban sugar selling agency had been set up, which was now dominated by Blanco? Others believed so. “Of Blanco,” Lobo later wrote intemperately, “nothing surprises me because he was a crook.” Raúl Cepero Bonilla, a respected economics correspondent, went further. He suggested the restrictions were solely designed to bail Blanco out of a huge speculative position. To cover it, Blanco needed prices to rise. Instead, they were continuing to fall, and Blanco faced a large margin call he could not afford to pay.

Bohemia

pointed out in an article, that Blanco, whose nephew managed Batista’s sugar mill Washington, had paid $24 million to Dr. Jorge Barroso, head of the Sugar Board. How interesting too that almost every morning Blanco visited Amadeo López Castro, the government’s representative at the committee on sugar sales. Was it as a result of this, perhaps, that a Cuban sugar selling agency had been set up, which was now dominated by Blanco? Others believed so. “Of Blanco,” Lobo later wrote intemperately, “nothing surprises me because he was a crook.” Raúl Cepero Bonilla, a respected economics correspondent, went further. He suggested the restrictions were solely designed to bail Blanco out of a huge speculative position. To cover it, Blanco needed prices to rise. Instead, they were continuing to fall, and Blanco faced a large margin call he could not afford to pay.

Blanco turned to Lobo for help, visiting him at the Galbán Lobo office with two officials from the Sugar Institute. Lobo obliged, buying 387,000 tons of sugar, worth some $30 million, that Blanco would otherwise have dumped on the market. It was not out of charity. Lobo believed Blanco was “an S.O.B. of the first order,” and acted only to prop up prices and so save his own and others’ positions. More remarkably, Lobo next approached the government. He offered to buy the surplus 1.8 million tons that Batista had planned to stockpile and keep back from the market. The Sugar Board refused. “We don’t deal with speculators,” said Barroso, despite his links with Blanco, one of the country’s biggest.

Undeterred, Lobo tried an even more ambitious ploy. Later that same year, on December 10, he visited Batista at Kuquine, the president’s luxurious

finca

outside Havana. They had first met almost exactly ten years ago when Lobo had attended a large banquet at the Waldorf Astoria in honor of the then newly elected president—a different man. That had been the “good Batista” of the 1930s and ’40s, a nimble and imaginative politician, with two Communist ministers in his cabinet, who transformed Cuba into a country with a large social safety net. This was the second, “bad” Batista of the 1950s who had emerged after the coup. Gone were the reputed sixteen-hour workdays of his first presidency. Instead Batista played canasta, watched horror films, and obsessed over minor details such as the correct tying of a tie or the punctuation of a letter. He was also less intent on winning popular support and, because his presidency came on the heels of Grau’s and Prío’s eight years of corruption, at first he did not need it. But opposition was growing quickly, and, soon, like all dictators, Batista would face a succession crisis, one that he resolved, as dictators so often do, by postponing elections and his scheduled departure from office. As in so many corrupt sultanates, his most creative schemes also involved growing his fortune and those of associates and friends.

finca

outside Havana. They had first met almost exactly ten years ago when Lobo had attended a large banquet at the Waldorf Astoria in honor of the then newly elected president—a different man. That had been the “good Batista” of the 1930s and ’40s, a nimble and imaginative politician, with two Communist ministers in his cabinet, who transformed Cuba into a country with a large social safety net. This was the second, “bad” Batista of the 1950s who had emerged after the coup. Gone were the reputed sixteen-hour workdays of his first presidency. Instead Batista played canasta, watched horror films, and obsessed over minor details such as the correct tying of a tie or the punctuation of a letter. He was also less intent on winning popular support and, because his presidency came on the heels of Grau’s and Prío’s eight years of corruption, at first he did not need it. But opposition was growing quickly, and, soon, like all dictators, Batista would face a succession crisis, one that he resolved, as dictators so often do, by postponing elections and his scheduled departure from office. As in so many corrupt sultanates, his most creative schemes also involved growing his fortune and those of associates and friends.

Batista received Lobo in splendor. In his private office there was a large painting of the president as a sergeant, a solid gold telephone, along with busts of Churchill, Gandhi, Stalin, Rommel, Joan of Arc, and the president himself. There were also the telescope Napoleon used on St. Helena, two pistols the emperor had used at Austerlitz, and, open on a lectern by the doorway, an 1822 edition of the

Vie politique et militaire de Napoléon

by Antoine-Vincent Arnault.

Vie politique et militaire de Napoléon

by Antoine-Vincent Arnault.

Lobo made the president his offer. He asked Batista to drop next year’s restrictions, adding that he would buy any sugar that Cuba produced over and above the three million tons destined to meet the U.S. quota and Cuba’s own needs. In effect, Lobo was saying, let the Cuban sugar crop rip and

he

would absorb it as a substitute world market. (Pleasing irony: Che Guevara would assert seven years later that Cuba, after it lost the U.S. quota, should become “master of the world market, able to dictate prices,” close to Lobo’s aim then.)

he

would absorb it as a substitute world market. (Pleasing irony: Che Guevara would assert seven years later that Cuba, after it lost the U.S. quota, should become “master of the world market, able to dictate prices,” close to Lobo’s aim then.)

Batista asked Lobo what price he had in mind. Lobo offered three cents a pound, slightly less than the prevailing world price, with the only provision that he would take all profits if the sugar price rose above that level, tax free.

It would be a huge position, over three million tons, Lobo estimated, worth some $225 million, or $2 billion now. The risks were tremendous. If Cuba produced as much sugar as it could, world prices could plummet—and Lobo would lose a fortune. But from his London agents, Lobo believed that Britain, after thirteen years of postwar sugar rationing, was poised to lift restrictions, and that extra demand from the sweet-toothed English would support the market. Mujal, head of the workers’ union and present at the meeting, thought otherwise. He told Batista that Churchill would tighten further the British belt, and Lobo’s plan was thus doomed to fail. That would ruin Lobo and possibly Cuba. Batista refused the offer, although events soon proved Lobo’s prediction right. On February 5, 1953, Churchill began to lift Britain’s sugar rations, and there was a rush on stores as schoolchildren emptied their piggy banks and men in pin-striped suits queued to buy boiled sweets during their lunch breaks in the City of London.

Barroso, head of the sugar board, worked hard to mask the failures of Batista’s sugar policy. He praised the decision to restrict exports, claiming it “had staved off the collapse of the Cuban economy and the sugar industry.” For this fealty, Barroso was rewarded with a ministerial post. Yet Cuban abnegation did little to help prices. By the end of 1953, sugar traded at 3.1 cents per pound, much as it had a year ago and only slightly above Lobo’s offer. Producers elsewhere meanwhile ground their sugar merrily, just as Lobo and others had predicted they would. Baron Paul Kronacher, a Belgian producer and occasional visitor at Tinguaro, built a huge sugar mill in the Congo, while one enterprising Cuban

hacendado

, Jesus Azqueta, developed a mill in Venezuela, in part to circumvent Batista’s restrictions. Lobo could have done the same but believed it “undignified,” even if good business, to compete from abroad against Cuba, the country to which he owed his fortune. Prices continued to fall, as did the Cuban crop: by 1955 it had dropped a third to 4.5 million tons, while world production rose to fill the gap Cuba had left.

hacendado

, Jesus Azqueta, developed a mill in Venezuela, in part to circumvent Batista’s restrictions. Lobo could have done the same but believed it “undignified,” even if good business, to compete from abroad against Cuba, the country to which he owed his fortune. Prices continued to fall, as did the Cuban crop: by 1955 it had dropped a third to 4.5 million tons, while world production rose to fill the gap Cuba had left.

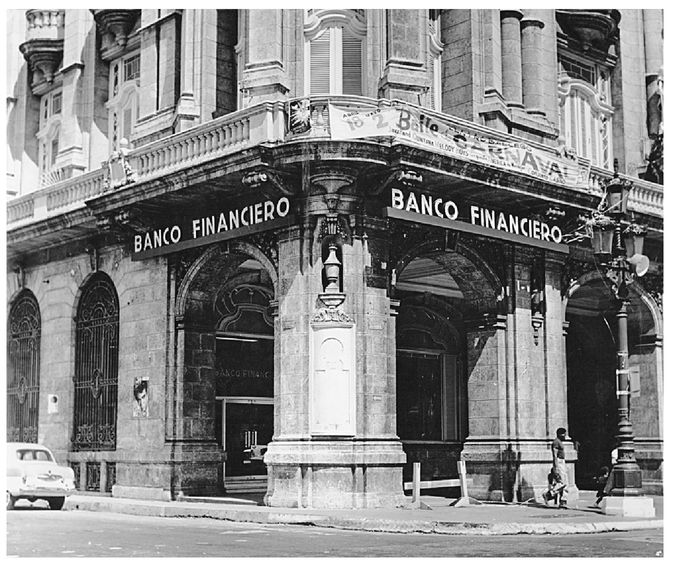

His grand stratagems thwarted, Lobo returned to his entertainments at Tinguaro, his love affairs, and the Napoleon library at his Vedado home. He was in a philosophic mood, yet ready to hatch new plans. In the middle of 1953, he founded a new enterprise, Banco Financiero. He also started to buy mills again, beginning negotiations to buy his twelfth, Araújo in Matanzas, while also consolidating control at another, Unión.

It was the same pattern as after the Second World War, when restric-tions had limited Lobo’s scope for market speculation and he had channeled his energies elsewhere. The difference this time was his health, which was failing. He suffered a mild heart attack in the spring of 1953 and a more serious stroke that summer. Batista’s presidency also suffered its first serious blow that summer after Castro launched a rebel attack on the Moncada military barracks in Santiago. The raid failed, and Castro was captured and sentenced to prison. But Batista, believing his position secure, granted an amnesty in May 1955 and Castro left for Mexico shortly after, where he met Che Guevara for the first time. Together they made plans to launch an invasion of Cuba in December the following year under the banner of the 26 July movement, the date of the Moncada attack.

Other books

Shifters of Grrr 1 by Artemis Wolffe, Terra Wolf, Wednesday Raven, Amelia Jade, Mercy May, Jacklyn Black, Rachael Slate, Emerald Wright, Shelley Shifter, Eve Hunter

Eden's Garden by Juliet Greenwood

Eternal Flame (Eternal Flame #1) by Sofia Giselle

Uncovering Helena by Kamilla Murphy

The Memoirs of Irene Adler: The Irene Adler Trilogy by San Cassimally

The Sari Shop Widow by Shobhan Bantwal

Game Of Risk (Risqué #3) by Scarlett Finn

These Starcrossed Lives of Ours by Linski, Megan

Cry No More by Linda Howard

Murder at Ebbets Field by Troy Soos