The Sugar King of Havana (27 page)

Read The Sugar King of Havana Online

Authors: John Paul Rathbone

“But Daddy!” they chorused, flushed with the excitement of having stood so close to a Hollywood star. “That was

Joan Fontaine

, and you didn’t even notice.”

Joan Fontaine

, and you didn’t even notice.”

“I see,” replied Lobo, who hadn’t. He thought for a moment, and lifted up the phone.

“I would like to leave a message for Miss Joan Fontaine,” he told the hotel operator. “A mutual friend of ours insisted that I call her when I passed through London.”

The girls were aghast at the fabrication. But a few minutes later the phone rang with Fontaine on the line. Lobo’s eyes lit up and they arranged to meet in the lobby for a drink.

The girls teased their father the next day. Many years later Lobo told Fontaine that the evening “was one of the outstanding moments in my life”—he always knew how to pay a beautiful woman a compliment. At the time he only commented that the London sky was very beautiful at night.

Lobo’s charm is apparent in the relationship he struck up with Fontaine’s mother, Lillian. A formidable woman, often estranged from her two daughters, Joan Fontaine and the actress Olivia de Havilland, Lillian developed a deep fondness for Lobo over a correspondence that spanned twenty years. The affection was mutual. Lobo sent her rare books, such as

The Art of Worldly Wisdom

by the Spanish friar Baltasar Gracián, and the sayings of the Greek philosopher Epictetus. (“I am certain both will become part of your bedside literature,” he wrote. After his shooting, Lobo was nothing if not stoic.) He also sent music, including an original score by Camille Saint-Saëns (“rather unusual; I trust you will like it”), recordings of Haydn and Bach, with Lobo often gently teasing Lillian in the accompanying letters. In one he asks if she had received a recording of the Cuban zarzuela “Cecilia Valdés” and then says music doesn’t really move him, quoting Lorenzo’s speech in

The Merchant of Venice

about the dangers of “the man that hath no music in himself.” Lobo joked: “So beware! I really must be a bad character!” Neither Lillian nor Joan Fontaine ever found him so.

The Art of Worldly Wisdom

by the Spanish friar Baltasar Gracián, and the sayings of the Greek philosopher Epictetus. (“I am certain both will become part of your bedside literature,” he wrote. After his shooting, Lobo was nothing if not stoic.) He also sent music, including an original score by Camille Saint-Saëns (“rather unusual; I trust you will like it”), recordings of Haydn and Bach, with Lobo often gently teasing Lillian in the accompanying letters. In one he asks if she had received a recording of the Cuban zarzuela “Cecilia Valdés” and then says music doesn’t really move him, quoting Lorenzo’s speech in

The Merchant of Venice

about the dangers of “the man that hath no music in himself.” Lobo joked: “So beware! I really must be a bad character!” Neither Lillian nor Joan Fontaine ever found him so.

I telephoned Joan Fontaine in Los Angeles, having written a few weeks before. I had been warned that she refused most interview requests and lived in near seclusion, preferring a quiet life and gardening. Speaking about Lobo was clearly an exception. Fontaine greeted my call with a firm, bright voice.

“Oh, I am so glad you called. I’ve been thinking so much about him since you wrote. I adored Julio—he was the best friend I ever had.”

There was a whistle of air and static on the line as we talked.

“Wasn’t he driving the car when he was shot?” remembered Fontaine. “I think he was.”

Sushh

, whispered the telephone. “And didn’t he fall on the car horn when he was wounded? I think that is right too.”

Sushh

, whispered the telephone. “And didn’t he fall on the car horn when he was wounded? I think that is right too.”

Lobo eventually proposed to Fontaine. “I couldn’t—it would have been like marrying my father,” she told me. “Julio was like my adviser, he was always there during the hardest times of my life.”

To his credit, Lobo easily made the transition from suitor to friend. In later years, he called Fontaine a person among his “first row,” and valued her above all for her companionship, even though he also thought her

loca

, a bit crazy. “As you know, early in the 1950s I very much wanted to marry you,” Lobo wrote to Fontaine in his eighties. “I suppose that now, looking back, I understand why you got cold feet at the last moment. I think that perhaps you did the right thing.”

loca

, a bit crazy. “As you know, early in the 1950s I very much wanted to marry you,” Lobo wrote to Fontaine in his eighties. “I suppose that now, looking back, I understand why you got cold feet at the last moment. I think that perhaps you did the right thing.”

Perhaps Lobo was deluded to think Fontaine would ever have agreed to marry him. He may also only have been trying it on, floating the suggestion out of curiosity to see how she reacted. Still, it is striking how frank Lobo and Fontaine are with each other in the letters that they exchanged in the last years of his life, and how tender. “Like you, I am a loner and relish solitude and actually require it,” she wrote in 1981 when, for a moment, it appeared that Lobo might move to the United States to be nearer his old flame during the last two years of his life.

“I am so glad you were touched by my letter for I meant every word of it,” Fontaine wrote. “My apartment is on a floor with an elevator so your visits here could be easily managed. And I have a large leather arm chair with a foot stool by my library fire that would fit you! I am hungry for good conversation and never had better ones than with you.”

They had much in common: an interest in books, in archaeology, and a similarly turbulent family life. Fontaine had a lifelong rivalry with her sister, Olivia de Havilland, an enmity that had a special resonance for Lobo, given the antagonism his two daughters felt for each other. “The sadness which envelopes my heart is very great because the two girls do not talk to each other,” he wrote to Fontaine in 1977. Perhaps because of this, Lobo was one of the few people to bridge the Fontaine–de Havilland rift. Although his letters to de Havilland never approached the same warmth as those to Fontaine, he corresponded often and took a medical interest in her son, who suffered from Hodgkin’s disease, Lobo sending her clippings of the latest treatments.

Fontaine learned about Lobo’s death long after the fact. “I only found out when his secretary wrote to me,” she told me. “But the letter was translated from the Spanish and there was no sense in it that he had gone.” Fontaine paused, the gurgle of our phone connection filling the silence. “I miss him so much.”

Fontaine’s initial brightness had faded, and I didn’t have the heart to ask this nonagenarian former Hollywood icon why she hadn’t mentioned Lobo in her memoir,

No Bed of Roses

, an omission that had hurt him.

No Bed of Roses

, an omission that had hurt him.

Fontaine closed bravely. “Is there anything more I can tell you? I hope that I have been of help. There are so many emotions going through me right now. Goodbye. Oh dear,” she said, and put down the phone.

THE CONVERSATION I HAD with Fontaine made me think of Tinguaro, Lobo’s Shangri-la. She had often stayed there alongside the writers, painters, diplomats, artists, and English lords Lobo invited to the mill. The singer Maurice Chevalier came, as did the

New Yorker

cartoonist Charles Addams, Ginger Rogers, Merle Oberon, and Cesar Romero, best known for his role as the Joker in the

Batman

television series but whose other claim to fame was as José Martí’s illegitimate grandson. The only people rarely present were Cuban politicians. Esther Williams remembered the plantation fondly in her memoir,

The Million Dollar Mermaid.

New Yorker

cartoonist Charles Addams, Ginger Rogers, Merle Oberon, and Cesar Romero, best known for his role as the Joker in the

Batman

television series but whose other claim to fame was as José Martí’s illegitimate grandson. The only people rarely present were Cuban politicians. Esther Williams remembered the plantation fondly in her memoir,

The Million Dollar Mermaid.

Years ago, when I was still at MGM, Ben [ Williams’s then-husband] and I had gone on a junket to Cuba with Cesar Romero and a group of wealthy MGM investors. Julio Lobo . . . had been our host. . . . He had a magnificent villa. . . . There had been some magnificent parties, and Julio had extended an effusive, open-ended invitation to come whenever I wanted.

Lobo’s hospitality grew out of the traditional generosity exhibited by all Cuban

hacendados

. Baron von Humboldt, the nineteenth-century German naturalist who knew high society in Europe and the Americas, observed that “hospitality, which generally diminishes as civilization advances, is still practiced in Cuba with the same profusion as it is in the most distant Spanish American lands.” Of that profusion, there is this description by a traveling Bostonian businessman of one particularly opulent nineteenth-century plantation. “The luxuriousness of the residence is known throughout the island. Its stables have space for fifty horses. The house, of one floor, has internal patios that cover a huge area; it could accommodate at least one hundred people. . . . You arrive at its roman baths, of exquisite marble, by an avenue of bamboos that form an arching roof seventy feet high. . . . It seems like a fairy tale. . . . In the morning, gin flowed from a fountain in the garden, and in the afternoon there burbled a flow of Cologne, to the delight of the guests.”

hacendados

. Baron von Humboldt, the nineteenth-century German naturalist who knew high society in Europe and the Americas, observed that “hospitality, which generally diminishes as civilization advances, is still practiced in Cuba with the same profusion as it is in the most distant Spanish American lands.” Of that profusion, there is this description by a traveling Bostonian businessman of one particularly opulent nineteenth-century plantation. “The luxuriousness of the residence is known throughout the island. Its stables have space for fifty horses. The house, of one floor, has internal patios that cover a huge area; it could accommodate at least one hundred people. . . . You arrive at its roman baths, of exquisite marble, by an avenue of bamboos that form an arching roof seventy feet high. . . . It seems like a fairy tale. . . . In the morning, gin flowed from a fountain in the garden, and in the afternoon there burbled a flow of Cologne, to the delight of the guests.”

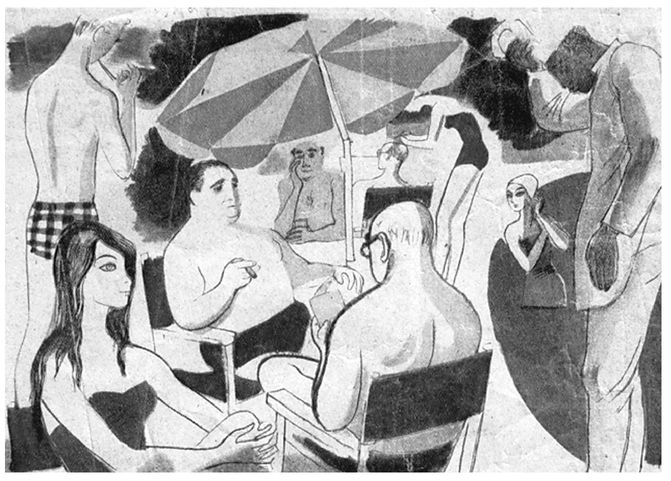

An Afternoon at Tinguaro,

by Hipólito Caviedes.

by Hipólito Caviedes.

While welcoming, Lobo disdained such showiness. In 1950, when he offered a joint coming-out party for his daughters with four hundred guests, María Luisa wrote to her father saying she had found a beautiful dress in New York for $600. Lobo sent a curt reply: “You know I am modest in my habits and way of life and that I hate ostentation, a sign of bad taste and the ‘nouveau riche,’ ” and he recommended that she find a cheaper dress in Havana. Rather than amid brazen luxury, Lobo’s guests at Tinguaro slept in a modest if well-appointed

casa de vivienda,

a staggered row of clapboard buildings, with air-conditioned rooms and white porches joined by stone paths that curved through well-tended lawns. During the day, they rode on horses through the grounds or socialized around the pool. In the evening, a local orchestra composed of plantation workers played during dinner. Fireflies danced in the bushes, and the mill puffed and groaned in the background with a comforting hum. Hipólito Caviedes, the Spanish artist who painted the mural at the Galbán Lobo office in Havana, remembered—and drew—a typical afternoon:

casa de vivienda,

a staggered row of clapboard buildings, with air-conditioned rooms and white porches joined by stone paths that curved through well-tended lawns. During the day, they rode on horses through the grounds or socialized around the pool. In the evening, a local orchestra composed of plantation workers played during dinner. Fireflies danced in the bushes, and the mill puffed and groaned in the background with a comforting hum. Hipólito Caviedes, the Spanish artist who painted the mural at the Galbán Lobo office in Havana, remembered—and drew—a typical afternoon:

When Hollywood stars visit . . . their beauty is a wonderful compliment to the surrounding countryside. Joan Fontaine is an island apart, with her enchanting intelligence. Esther, the Venus of the day, bounces off the springboard and splashes the less athletic around the pool. . . . Carlos chooses a recording of violin music while discoursing on “hifidelity” versus “hi-

infidelity.

” Someone else cuts the hair of the Italian ambassador, while he reads the score of a Bach sonata. . . . While all this goes on, Julio periodically receives enigmatic messages from the office written on blue or yellow slips of paper: glucose, lactose, polarization, the state of sugar production at 4.30pm.

infidelity.

” Someone else cuts the hair of the Italian ambassador, while he reads the score of a Bach sonata. . . . While all this goes on, Julio periodically receives enigmatic messages from the office written on blue or yellow slips of paper: glucose, lactose, polarization, the state of sugar production at 4.30pm.

Even in swimming trunks, Lobo was always at work, reading dispatches, taking phone calls, compartmentalizing his attention so that he could read a telegram, play the sugar market, or act as gracious host at the same time. It was this constant activity, plus the horn of the plantation train, the smoke from the mill’s chimneys, the sweet smell of molasses, the sound of the carts bringing cane from the field, and the factory whistle, which announced the change of shifts during the height of the

zafra,

that saved Tinguaro from a

Dolce Vita

decadence. Lobo wanted Tinguaro to be a Shangri-la for all, including the families that worked there. The American bankers who sold Lobo the mill in 1944 had told him that Tinguaro’s “land was bad, the cane was bad, the mill was bad—but worst of all were the people.” Lobo set out to prove them wrong. Everybody at Tinguaro knew him as Julio, from Lola the maid or El Chino the Communist carpenter to the bishop of Matanzas, who inaugurated the chapel named after his mother’s saint’s day, Eduvigis.

zafra,

that saved Tinguaro from a

Dolce Vita

decadence. Lobo wanted Tinguaro to be a Shangri-la for all, including the families that worked there. The American bankers who sold Lobo the mill in 1944 had told him that Tinguaro’s “land was bad, the cane was bad, the mill was bad—but worst of all were the people.” Lobo set out to prove them wrong. Everybody at Tinguaro knew him as Julio, from Lola the maid or El Chino the Communist carpenter to the bishop of Matanzas, who inaugurated the chapel named after his mother’s saint’s day, Eduvigis.

Tinguaro’s swimming pool.

Lobo built a clinic, a small library, a primary school, and provided scholarships for promising students. When Havana’s Malecón was remodeled, he also bought the seafront’s discarded belle époque streetlamps and stationed them on street corners throughout the

batey

. He refurbished houses, paved street sidewalks, and modernized the mill as much as Cuban labor laws allowed. A tunnel was dug to transport the milled bagasse cane stalks more easily to the furnaces that powered the grinders, and the machines were painted a smart orange so that leaks and grease could be noticed quickly and cleared. “A sugar factory should be as clean and as hygienic as any other food processing plant, such as one that makes condensed milk,” Lobo wrote. When he took ownership, Tinguaro milled around twenty thousand tons of sugar a year. Twenty years later, it produced three times that amount.

batey

. He refurbished houses, paved street sidewalks, and modernized the mill as much as Cuban labor laws allowed. A tunnel was dug to transport the milled bagasse cane stalks more easily to the furnaces that powered the grinders, and the machines were painted a smart orange so that leaks and grease could be noticed quickly and cleared. “A sugar factory should be as clean and as hygienic as any other food processing plant, such as one that makes condensed milk,” Lobo wrote. When he took ownership, Tinguaro milled around twenty thousand tons of sugar a year. Twenty years later, it produced three times that amount.

“We spent a lovely weekend at Tinguaro during the May day holiday,” Lobo wrote to María Luisa in 1950, wishing that she could have been there too. While some guests sang, others painted, and “everyone did their thing, except for me, who played at being master of ceremonies.” When María Luisa did go to Tinguaro, my mother sometimes went with her too. There she swam in the pool, flirted with Havana’s young Turks, and drank cocktails with the rest of Cuba’s

jeunesse dorée

. One of the pictures in her albums shows her sitting cross-legged on the diving board, wearing shorts and a loose shirt, beaming, obviously happy. Another shows a group of six friends crouched in the shallows of the swimming pool, the midday sun bouncing off the water, all smiling, some wearing sunglasses, arms around one another’s shoulders, drinks in their hands raised in a toast.

jeunesse dorée

. One of the pictures in her albums shows her sitting cross-legged on the diving board, wearing shorts and a loose shirt, beaming, obviously happy. Another shows a group of six friends crouched in the shallows of the swimming pool, the midday sun bouncing off the water, all smiling, some wearing sunglasses, arms around one another’s shoulders, drinks in their hands raised in a toast.

Other books

The Prodigal Comes Home by Kathryn Springer

Beneath the Dark Ice by Greig Beck

StrategicLust by Elizabeth Lapthorne

Unnatural by Michael Griffo

Firehurler (Twinborn Trilogy) by Morin, J.S.

A Good Man Gone (Mercy Watts Mysteries) by A.W. Hartoin

Erin's Awakening by Sasha Parker

The Princess of Cortova by Diane Stanley

Witch Is Why The Laughter Stopped (A Witch P.I. Mystery Book 14) by Adele Abbott

Compelled by Carla Krae