The Sugar King of Havana (31 page)

Read The Sugar King of Havana Online

Authors: John Paul Rathbone

The legacy of this prosperity can still be seen in Havana districts such as Miramar, beyond the shopping district of El Centro and the hotels, businesses, and all-night cafés that lined La Rampa, the broad avenue that rises from the Malecón into Vedado. Planted with large shade trees, Miramar still exudes a plush restfulness, with balconied houses set back from the streets amid generous gardens. Most impressive are such suburbs’ size. Miramar alone runs for a hundred blocks. And beyond Miramar the white stucco houses keep on going, through the quiet streets of residential areas now called Siboney, Náutico, Flores, and Cubanacán.

In the mid-1950s, Havana became known as the “Paris of the Caribbean,” the “Monte Carlo of the Americas,” the greatest party town on earth. Its nightlife was compared to that of prewar Paris or Berlin. There were flawless suits and glittering casinos, hot dance music and seductive showgirls, guerrillas in the mountains and repressive policemen in the streets. The city’s “gangster chic,” as Mob historian T. J. English describes it, so redolent of the golden age of Hollywood, was part of Havana’s glamour, and glamour generates myths, such as the valiant revolutionary during the last years of Batista who blew himself up after rushing a policeman. That, at any rate, was the scene that Don Michael Corleone saw from the back of his car when he came down to Havana in

The Godfather Part II

to try to secure his influence over the city’s casinos. Yet

The Godfather Part II

is just a movie, and the scene is only a plausible invention, since there is no record of a revolutionary suicide-bomber.

The Godfather Part II

to try to secure his influence over the city’s casinos. Yet

The Godfather Part II

is just a movie, and the scene is only a plausible invention, since there is no record of a revolutionary suicide-bomber.

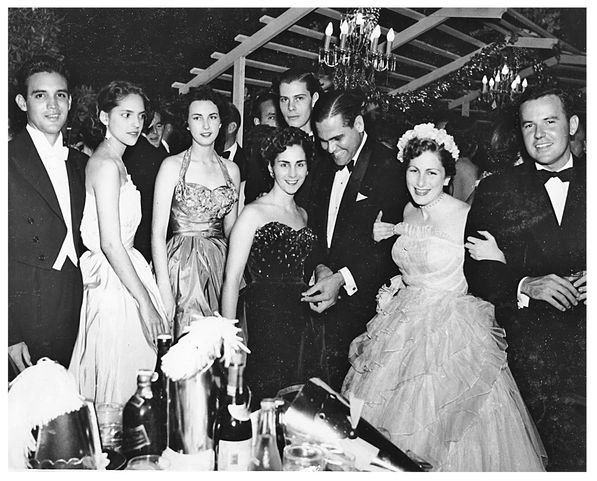

Members of my grandparents’ and mother’s generations living in Havana at the time would have been perplexed by the portrayal of their city in such films. And yet the Batista government did fall almost as rapidly as these movies depicted it. Then all the parties with the men in black tie, the women in cocktail dresses, the debutantes in fluffy confections of white silk and linen and tulle; the extravagant shows at the Tropicana; the Mafia, their casinos, and the famous American actor drunk in a small bar in Old Havana were suddenly over, gone with the wind, and the traces and stories that they left behind grew into legends. How could they not? A scene that bad was too good for any Hollywood screenwriter or revolutionary ideologue to ignore.

Havana Country Club, New Year’s Eve.

Leonor wears a dark dress in the middle; María Luisa is second from the right;

my mother second from the left.

Leonor wears a dark dress in the middle; María Luisa is second from the right;

my mother second from the left.

ONE DAY IN HAVANA, I went to a bougainvillea-shrouded street in Miramar to visit Guillermo Jiménez. A retired economist and journalist of distinction, Jiménez is also a decorated comandante who took a bullet in the fight against Batista fifty years ago. A wiry seventy-year-old, with a warm face, nervous hands, and a natty dress sense, Jiménez has the careful manner of someone who, like Cuba itself, has triumphed because he has survived. Unlike many, he looks forward to the future.

“Sometimes I get requests for interviews when there is some revolutionary anniversary or other,” he told me as we sat in his study, a shady room at the front of the house. “I am glad to help, but we have to get on, to live in the present.”

Such optimism about the future may be because Jiménez has spent so much time examining the past. When we met he had just completed the second of a planned four-volume economic history of prerevolutionary Cuba. The first describes its largest businesses; the second is a series of biographical sketches of their owners, the country’s 551 richest and most influential men and women (mostly men). The research is meticulous, shorn of inference and ideology. “Its eloquence, if there is any, stems only from the force and aridity of facts, without any interpolation by the author,” as Jiménez wrote in the preface. Indeed, with their crisp entries arranged in alphabetical order, the books have the utilitarian feel of a dictionary. They make “no concession to the reader,” as Jiménez said. All of which makes the success they have since enjoyed in Havana, and in samizdat versions in Miami, more surprising.

The second volume was released on June 2, 2007, at a launch party held at the Palacio del Segundo Cabo, a three-story colonial building in Old Havana with a fountain set in an inner courtyard. There had been a violent rainstorm the night before, and the Cuban book institute was hopeful of a good turnout. Soon they worried the second floor of the building might collapse under the weight of the eager audience. Some there recalled the crush in 1991 that had followed the reissue of José Lezama Lima’s baroque masterpiece

Paradiso.

Partly because of its homosexual references, the authorities had tacitly banned the novel after a limited print run in 1966.

Paradiso

’s rerelease two decades later was more of a rock concert than a book launch. People chanted “Paradise! Paradise! Paradise!”—a recovered Paradise—as the crowd ebbed and flowed from one floor of the building to another as rumor spread that copies would be sold upstairs, then downstairs, then outside. Although Jiménez’s history book does not pretend to be literature, sixteen years later there was pushing and shoving again in the Palacio del Segundo Cabo among the lines that formed in front of the two tables stacked with copies of his book, and a huge uproar when someone said there were only 150 copies to go around. The head of the institute rushed off to get more, assuring the crowd that if these ran out there would be an immediate reprint, ready in a month.

Paradiso.

Partly because of its homosexual references, the authorities had tacitly banned the novel after a limited print run in 1966.

Paradiso

’s rerelease two decades later was more of a rock concert than a book launch. People chanted “Paradise! Paradise! Paradise!”—a recovered Paradise—as the crowd ebbed and flowed from one floor of the building to another as rumor spread that copies would be sold upstairs, then downstairs, then outside. Although Jiménez’s history book does not pretend to be literature, sixteen years later there was pushing and shoving again in the Palacio del Segundo Cabo among the lines that formed in front of the two tables stacked with copies of his book, and a huge uproar when someone said there were only 150 copies to go around. The head of the institute rushed off to get more, assuring the crowd that if these ran out there would be an immediate reprint, ready in a month.

Jiménez was characteristically modest about his book’s reception and genuinely puzzled too. Amid the crowd, he saw men and women he had not spoken to for years; old friends from the revolutionary struggle in the mountains, the city, and the plains. There were also journalists and novelists. One asked Jiménez to dedicate a copy, and then turned to a young poet next to him to explain the importance of the book. Jiménez could not understand the interest in his work, and was reticent to try and explain it.

It may be that the book is simply an invaluable work of reference and, in a country of frequent shortages, Cubans out of force of habit leap on anything that is useful. But the greater part of the interest, I believe, is that the book offers its readers a chance to escape the relentless drizzle of a historical past that Cubans have suffered, day by day, speech by speech, like acid rain. Jiménez said his motivation for writing the book was that young Cubans knew neither the capitalism, nor its capitalists, that once formed part of Cuban history. But it is also true that many

older

Cubans have little memory or understanding of prerevolutionary Cuban capitalists either. Their obvious interest in Jiménez’s book, it seemed to me, represented a hunger for something closer to a historical truth, and so also a step toward a reconciliation with Cuba’s past. There, detailed on paper, were the long-held and moneyed adversaries of the revolution: great capitalists like Lobo, powerful clans like the Falla-Gutiérrez and Bacardí families, their business interests calmly noted and accurately presented for the first time. Jiménez’s biographical sketches showed that behind the doctrine, source of so much division, there lay a people and humanity against which abstractions such as class struggle inevitably become remote, an observation as true of the men and women who once fought so bravely for the revolution as of those who subsequently fought against.

older

Cubans have little memory or understanding of prerevolutionary Cuban capitalists either. Their obvious interest in Jiménez’s book, it seemed to me, represented a hunger for something closer to a historical truth, and so also a step toward a reconciliation with Cuba’s past. There, detailed on paper, were the long-held and moneyed adversaries of the revolution: great capitalists like Lobo, powerful clans like the Falla-Gutiérrez and Bacardí families, their business interests calmly noted and accurately presented for the first time. Jiménez’s biographical sketches showed that behind the doctrine, source of so much division, there lay a people and humanity against which abstractions such as class struggle inevitably become remote, an observation as true of the men and women who once fought so bravely for the revolution as of those who subsequently fought against.

Leaf through the book and it becomes apparent that many of these 551

propietarios

were not the rapacious exploiters of the proletariat they are often thought to have been. Or if they were, in socially mobile Cuba some of them came from that same proletariat they exploited. One example is Vicente Domínguez, a mulatto cane cutter who got his break as a mechanic at Lobo’s first mill, Agabama. Domínguez later rented the mill from Lobo, with funds borrowed from Galbán Lobo, and was so successful that he went on to control five Cuban sugar mills, as well as another sugar interest in Haiti, later sold for $1 million. “Not bad for someone who did not know how to read or write,” Lobo commented.

propietarios

were not the rapacious exploiters of the proletariat they are often thought to have been. Or if they were, in socially mobile Cuba some of them came from that same proletariat they exploited. One example is Vicente Domínguez, a mulatto cane cutter who got his break as a mechanic at Lobo’s first mill, Agabama. Domínguez later rented the mill from Lobo, with funds borrowed from Galbán Lobo, and was so successful that he went on to control five Cuban sugar mills, as well as another sugar interest in Haiti, later sold for $1 million. “Not bad for someone who did not know how to read or write,” Lobo commented.

Batista’s entry is the longest, running to almost ten pages, twice the length of any other. But then it has to be. The dictator controlled some seventy businesses, including a bank, at least four sugar mills, swaths of Havana real estate, construction firms, one television station, two newspapers, various radio stations and hotels, and, most impressive of all, much of Cuba’s air and shipping networks, plus three quarters of its bus and road carriage companies. Perhaps it was because of his military past that Batista sought this strategic lock hold on Cuban transport.

Much of Batista’s wealth derived from gambling rackets or public contracts, from which he and his associates took a generous skim off the top. There was the tunnel built under the Havana Bay which linked the city to the beaches at Varadero in the east and was financed in a controversial deal criticized in the newspapers. There were also the expansion of the Rancho Boyeros airport and the new hotels that sprouted up in Havana, cofinanced by the notoriously corrupt state development bank Bandes, from which Bastista took his cut. The ubiquity of Batista’s businesses meant that getting ahead in Cuba, or even getting anything done, often required his involvement, and one unfortunate consequence of this was that it reduced civic duty to a simple philosophy: easier to pay off a public servant than to be one.

The only notable absence in Jiménez’s tour of Cuba’s prerevolutionary financial landscape is the Mafia, which kept a low profile, Lansky only ever appearing on his casino’s books as a minor administrator of the Riviera’s kitchens. Such shadowiness makes the Mob ripe for exaggeration, and it has become a postrevolutionary rite to conceive of Lansky, the “Mafia’s Henry Kissinger,” as a giant spider at the center of a web of corruption that controlled Havana, or indeed the whole country. The Mafia was certainly an important and corrupting force that coexisted with Batista. Yet Cuba produced much else in the 1950s besides casinos—not least sugar, the activity on which all other activities hung and which brought in ten times the revenues that tourism ever did.

Still, tourism was then Cuba’s fastest-growing industry. The number of hotel rooms in Havana doubled to 5,500 under a rule that allowed a casino to be added if more than $1 million was spent on a hotel. Pan American Airways made it easier to travel “down Havana way” by offering a $39 round-trip flight from Miami, advertised in newspapers up and down the east coast of the United States. A drive-on drive-off car ferry service opened between Florida and Havana, making the ninety-mile voyage in seven hours, at a cost of $23.50 per person round-trip. The boom was on.

Lobo could not but get involved, and Banco Financiero helped finance the construction of the Riviera and the Capri, both owned by the Mob. This did not make Lobo’s bank a front for Mafia money, although it did count among its shareholders Amadeo Barletta, a burly, silver-haired Italo-Cuban born to a wealthy family in Calabria.

A successful businessman, Barletta had moved to the Dominican Republic from Italy in the 1920s, where he opened a car dealership and served as Italian consul. In 1935, he was accused of attempting to assassinate the dictator Rafael Trujillo and was only saved thanks to Mussolini’s intercession. He had since settled in Havana, where he was known as the majority owner of the newspaper

El Mundo

and proprietor of the General Motors and Cadillac concessions, among other concerns. Suspected of Mafia links, although nothing was ever proved, Barletta was invited by Lobo into Banco Financiero as a minor shareholder in the hope that he would help broaden the bank’s business beyond sugar. Their association ended in 1957.

El Mundo

and proprietor of the General Motors and Cadillac concessions, among other concerns. Suspected of Mafia links, although nothing was ever proved, Barletta was invited by Lobo into Banco Financiero as a minor shareholder in the hope that he would help broaden the bank’s business beyond sugar. Their association ended in 1957.

Such intershading of interests and allegiances was inevitable. Although the drama is great, the stage was cramped, and Cuba was a small country marked by a dense and complex web of relationships that made it hard for anyone to claim to have never dealt with Batista, the Mob, the rebels, or often all three. In 1957, Lobo himself paid $25,000 to the Montecristi movement, a group allied to a military conspiracy against Batista. He paid a further $25,000 to Castro’s rebels in the Sierra after they threatened to burn his cane fields—the time-honored guerrilla tactic. Lawrence Berenson, Lobo’s old friend, was later taunted for knowing someone who had aided the rebels, although Lobo was far from being the only businessman to do so. Both Castros later singled out the Bacardís for their help in the Sierra. And the son of Lobo’s oldest friend George Fowler, owner of the Narcisa, a mill in Las Villas, was actively engaged in Castro’s 26 July movement. Anyway, if Lobo really had had Mafia connections, as some writers have since argued, it is doubtful so many senior government members, including Che Guevara, would later wear any previous association with him as a badge of their own professionalism. Raúl León Torres, a die-hard Communist who served as vice-minister of commerce and head of the Cuban National Bank, often boasted to Spanish officials in the 1970s that he had once worked with Lobo.

Instead, in Mafia-infested and corrupt Cuba—at least as conventionally remembered—Lobo made his money on his own terms, using his wits and guile. It was a point of pride. “I’d feel intellectually degraded if I ever obtained a success thanks to the help of some dishonest government functionary,” he once told León. Such pig-headedness made Lobo unforgiving and stubborn, qualities that won him more critics than admirers. “But if he had not been like that he would not have created. He would have been paralyzed,” as Rosario Rexach, León’s wife, remembered him. “And every leader, before anything else, is a man of action.” Indeed, it was this appetite for action that led Lobo to embark on one of his most stubbornly pursued and audacious deals. Only later would he view the $25 million purchase of the three Hershey sugar mills outside Havana as his Waterloo, the moment that he returned to in exile when times seemed bleakest, just as Napoleon returned to Waterloo during his most pessimistic moments on St. Helena. “There were many

comemierdas

, or assholes, in Cuba,” Lobo wrote in one bitter letter from Spain. “Hershey showed I was the biggest of them all.”

comemierdas

, or assholes, in Cuba,” Lobo wrote in one bitter letter from Spain. “Hershey showed I was the biggest of them all.”

Other books

Deliver Us from Evil by Robin Caroll

Shatter by Joan Swan

Clan and Conviction (Clan Beginnings) by Tracy St. John

025 Rich and Dangerous by Carolyn Keene

A Woman on the Edge of Time by Gavron, Jeremy;

Passions Recalled: Forbidden Passions, Book 2 by Loribelle Hunt

The Winter Long by Seanan McGuire

The Web by Jonathan Kellerman

Hillary_Tail of the Dog by Angel Gelique