The Sugar King of Havana (26 page)

Read The Sugar King of Havana Online

Authors: John Paul Rathbone

Lobo’s Napoleon-bedecked sitting room. Havana, 1958.

Lobo’s collection was the extravagance of a true collector. It was obsessive and unnecessary, yet by definition all great private collections are so. In 1959, when Lobo privately published a volume of letters between Napoleon and the Comte de Mollien, his minister of finance, General Charles de Gaulle, another difficult man with a sense of destiny, wrote from Paris to thank Lobo for “this priceless contribution to the study of the Imperial Age.”

Today, most of Lobo’s Napoleonic books are kept on the top floor of the museum. Ringed by a breezy terrace, it is the only bright room in the old house. Wooden shelves run down both sides, bursting with leather-bound books, some with the initials “JL” gold-embossed on their spines. When I asked one of the attendants if I could open a book, just to have a peek, she said no, reflexively, although perhaps the supervisor might be able to help. I climbed down the marble steps, knocked on the cracked window of an office on the ground floor that overlooked the garden, and a thin woman with the beleaguered look of a minor civil servant came out. We sat in the shade of an arbor overflowing with pink and orange bougainvillea, and she politely explained, with a resigned sense of the absurd, that

tristemente

, sadly, nobody was allowed to consult the books, not even professional Napoleon researchers. It was the common story of modern Cuba. That which should be possible is forbidden. Everything else is illegal.

tristemente

, sadly, nobody was allowed to consult the books, not even professional Napoleon researchers. It was the common story of modern Cuba. That which should be possible is forbidden. Everything else is illegal.

It would be fascinating to know more about what Lobo thought about Napoleon—especially as his hero was responsible for the industrial development of beet sugar after the English blockade reduced Caribbean sugar supplies to France. The shortages were such that imperial dignitaries were known to suspend a piece of sugar on a string from the ceiling, with each member of the family allowed to dip it into their cup only briefly. Sadly, only scraps of Lobo’s views survive. He jotted down asides in the margins of the histories, memoirs, and biographies that he collected, scribbling

FALSO

next to statements he disagreed with. (Here, as in much else, Lobo had made up his mind.) But most of these thoughts are now sealed off in the museum’s bookshelves—or lost in semidarkness in the subterranean archives of Cuba’s National Library. The other day, an archivist announced with great fanfare that he had found a complete ten-volume edition of rare Egyptian drawings that Napoleon had commissioned, part of the study of Egyptology that he invented, and that had once formed part of Lobo’s collection but had since moldered in a library basement for fifty years.

FALSO

next to statements he disagreed with. (Here, as in much else, Lobo had made up his mind.) But most of these thoughts are now sealed off in the museum’s bookshelves—or lost in semidarkness in the subterranean archives of Cuba’s National Library. The other day, an archivist announced with great fanfare that he had found a complete ten-volume edition of rare Egyptian drawings that Napoleon had commissioned, part of the study of Egyptology that he invented, and that had once formed part of Lobo’s collection but had since moldered in a library basement for fifty years.

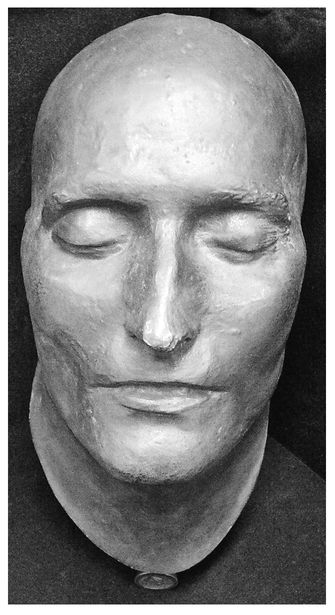

One of Lobo’s few surviving extended disquisitions concerns the emperor’s death mask, kept on a velvet cushion in a glass cabinet on the second floor of the museum. It is a scholarly article and tells a story curious for the macabre object itself, the long controversy that surrounded its maker, and how it arrived in Cuba.

Napoleon’s last physician, Francesco Antommarchi, was by the emperor’s bedside with several other members of the court when he died on the afternoon of May 5, 1821. At 5:51 p.m., the thirty-two-year-old Corsican-born doctor pronounced Napoleon officially dead and closed his open eyes. Napoleon’s body was laid out in the billiard room on a trestle table, and the following day Antommarchi performed an autopsy. He opened the cavity of the chest and removed the organs; Madame Bertrand, the wife of the Marshal of France, asked to keep the emperor’s heart, but her request was refused. Antommarchi then shaved Napoleon’s head and took precise measurements of the skull. The circumference was 22½ inches, an average size, despite most descriptions that agreed Napoleon’s head was disproportionately large for his body. “If we were to catalogue that in its most prosaic form, we would say that his head measured a hat size number 7,” as Lobo wrote.

Although Napoleon’s death had been foreseen for weeks, nobody had taken the precaution of gathering the chemicals necessary to embalm the great man’s body, let alone the plaster required to make a death mask. So that night an enterprising Englishman, Dr. Francis Burton, rowed out to a nearby island to collect some gypsum deposits. He roasted and crushed the crystals into a fine white powder, and on the afternoon of the following day made two molds, one of Napoleon’s face, the second of the back of his head and ears. The next day, Burton took positive casts and left them to dry. On his return, he discovered to his fury that Madame Bertrand, having failed to secure Napoleon’s heart, had packed the face mask in her bags and now refused to part with it. No more is known about the cast of the back of Napoleon’s head; according to some reports, Burton smashed it on the floor in anger at the theft. Madame Bertrand meanwhile took her mask to France.

Burton spent seven years trying to recover the property, but Madame Bertrand kept it with her. Antommarchi took a copy during a visit to her house in 1822 and, when Burton died six years later, made a limited edition in bronze and plaster, put forth his right as the author of the original, distributed several copies among Napoleon’s descendants, and left for the Americas with three others wrapped carefully in his bags.

He made for Santiago de Cuba, where a community of French plant-ers had settled after Haitian independence, including Antommarchi’s first cousin, Antonio, who owned a coffee farm thirty miles outside the city. Antommarchi arrived in November 1837 and set up what promised to be a thriving medical practice on the corner of Gallo and Toro streets. An operation on the cataracts of the Marquesa de las Delicias de Tempú was a notable early success. Unfortunately, the city was gripped by yellow fever at the time and Antommarchi had no natural immunity to the disease. He died just five months later, in the house of the Spanish governor, Brigadier General Juan de Moya y Morejón. The old soldier was Antommarchi’s closest friend in Cuba, despite the fact that he had lost an eye to Napoleon’s troops during the siege of Zaragoza.

Napoleon death mask.

Three Napoleon death masks radiate out from this point. Antommarchi had bequeathed two copies to friends in Santiago, one of which eventually found its way to Lobo’s collection. He gave a third to Dr. Wilson, a North American physician. Of the other imperial souvenirs that Antommarchi brought to Cuba, such as the silver dinner service, the locks of hair he shaved from the emperor’s head, and the other body parts he kept, nothing is known. They may still be in Cuba today.

Antommarchi was buried quickly because of the heat, and when his body proved too big to fit into General Moya’s private tomb, the Marqués de Tempú provided his own, “in gratitude for the operation on his mother’s eyes.” Antommarchi’s remains were later transferred to the Santa Ifigenia cemetery in Santiago where they now rest, mingled with the remains of the Tempús and alongside better-known figures from Cuban history, including the grave of José Martí himself. It is a mournful postscript to the story that a French plan to erect a large structure in the Santiago cemetery to honor the emperor’s physician came to naught. Still, as Napoleon once said: “It is the cause and not the death that makes the martyr.”

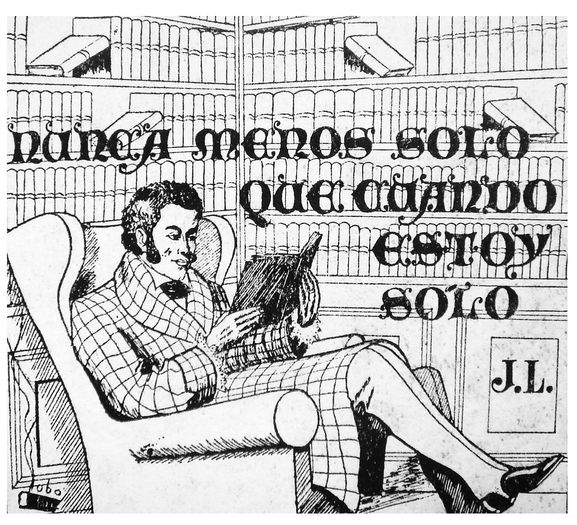

THE IMAGE OF LOBO researching an article about Napoleon’s death mask in his private library in a pool of light is a lonely one. Werner Muensterberger, a psychoanalyst who has made a study of collectors, has even called collecting a reaction to “the trauma of aloneness.” Lobo was certainly a loner by temperament, and the constant physical pain that he suffered after the shooting, plus the end of his marriage shortly after, would only have increased this natural instinct to retire into himself. The ex libris that Lobo’s assistants pasted into his books even showed a picture, drawn by Lobo, of a Byronic-looking squire in a checked dressing gown, reading in a wingback chair. Above runs a legend in Gothic letters:

Nunca menos solo que cuando estoy solo

, never less lonely than when I am alone.

Nunca menos solo que cuando estoy solo

, never less lonely than when I am alone.

Obsessive collectors are also frequently bachelors, which may be why Lobo collected women too. His divorce from María Esperanza marked the beginning of what Margarita González, Lobo’s assistant in New York, referred to as his “playboy years,” even if Lobo only partly matched the required profile of a playboy. He had a good wardrobe, if not good looks. He had languages, manners honed into reflexes, wit, a sense of humor, connections, wealth, and intelligence—both bookish and worldly. Extra points: he had a reputation for dangerousness. This transformed the artery that could be seen faintly pulsing in a soft patch at the back of his skull, where a bullet had plowed through bone, into a roguish attraction. Unlike the shy and withdrawn María Esperanza, the women Lobo courted were also fiery and strong-willed, somewhat like Napoleon’s first wife herself, the worldly Josephine, second daughter of a Martinique sugar planter, whose memoir was the last book Napoleon ever read. “I really loved her,” the emperor announced suddenly to his court one day, six weeks before he died, perhaps remembering Josephine’s indolent Caribbean walk, musical voice, and large eyes—if not her teeth, blackened by a childhood of chewing sugarcane. “She had something, I don’t quite know what. . . . She was a real woman. She had the sweetest little backside in the world.”

Lobo’s ex libris.

Josephine was the woman who broke Napoleon’s heart, and after their divorce—because she could not bear him an heir—the emperor took up with a string of actresses, even sharing one with his conqueror the Duke of Wellington. (Mademoiselle George later observed indiscreetly that the Iron Duke, as a lover, was “

le plus fort,

” perhaps in revenge for Napoleon’s once describing the act of love as “an exchange of perspirations.”) So Lobo had actresses in common with Napoleon too. Movie stars often visited Cuba during the golden age of Hollywood, and although Lobo was only tangentially part of this world, gossip columnist Hedda Hopper was a close friend and mentioned him often in her newspaper columns. Unlike Napoleon, however, Lobo was no misogynist. He remembered his former lovers to the end, remaining firm friends, often corresponding with them until his last years. One of the most famous was the Hollywood icon Joan Fontaine.

le plus fort,

” perhaps in revenge for Napoleon’s once describing the act of love as “an exchange of perspirations.”) So Lobo had actresses in common with Napoleon too. Movie stars often visited Cuba during the golden age of Hollywood, and although Lobo was only tangentially part of this world, gossip columnist Hedda Hopper was a close friend and mentioned him often in her newspaper columns. Unlike Napoleon, however, Lobo was no misogynist. He remembered his former lovers to the end, remaining firm friends, often corresponding with them until his last years. One of the most famous was the Hollywood icon Joan Fontaine.

Fontaine is best remembered for her lead role in Alfred Hitchcock’s celebrated 1940 version of Daphne du Maurier’s gothic novel

Rebecca.

She plays the cowed second wife of a rich Englishman, Max de Winter, portrayed in clipped style by Laurence Olivier. The drama takes place in a seaside Cornish mansion haunted by the memory of de Winter’s first wife, Rebecca, who died in a mysterious boating accident. As is so often the case, Fontaine’s demure screen image belied the actress’s true personality.

Rebecca.

She plays the cowed second wife of a rich Englishman, Max de Winter, portrayed in clipped style by Laurence Olivier. The drama takes place in a seaside Cornish mansion haunted by the memory of de Winter’s first wife, Rebecca, who died in a mysterious boating accident. As is so often the case, Fontaine’s demure screen image belied the actress’s true personality.

Du Maurier had written the book while living in Egypt with her husband, desperately missing her home by the Cornish sea, a place of rocks, dark nights, and smugglers’ coves. Du Maurier wrote that the homesickness she felt in Egypt was “like a pain under the heart continually.” Hitchcock captures this dreamy longing in the watery unconsciousness of a crashing sea, and in the flickering light that plays across Fontaine’s face. In

Rebecca

, she wrings her hands, rarely raises her eyes, and speaks in a voice that alternates between a monotone and a quavering tentative-ness. Fontaine later struggled to escape the typecasting. It was only in later years, with her patrician beauty and sharp intelligence, that reviewers praised Fontaine for her “majestic stride and presence, robust humor and sense of the dramatic,” as one critic noted in a 1979 comeback performance of

The Lion in Winter,

a review that Lobo clipped when he was a lion in winter himself.

Rebecca

, she wrings her hands, rarely raises her eyes, and speaks in a voice that alternates between a monotone and a quavering tentative-ness. Fontaine later struggled to escape the typecasting. It was only in later years, with her patrician beauty and sharp intelligence, that reviewers praised Fontaine for her “majestic stride and presence, robust humor and sense of the dramatic,” as one critic noted in a 1979 comeback performance of

The Lion in Winter,

a review that Lobo clipped when he was a lion in winter himself.

Lobo and Fontaine first met during the winter of 1951 in a psychologically cramped setting worthy of any Hitchcock film: a hotel elevator. Lobo was in London with his daughters to open a branch of the Galbán Lobo office. Fontaine was in England to film

Ivanhoe

, playing the part of Lady Rowena, opposite Elizabeth Taylor. Unbeknownst to each other, they were staying at the same hotel, Claridge’s. After dinner in the hotel restaurant, Lobo and his two teenage daughters went up to their rooms, Fontaine stepping inside the lift as the doors closed behind them. Lobo took no notice, burying his nose deeper into a newspaper as the bell pinged at each floor. Leonor remembers how she and María Luisa meanwhile elbowed each other in the ribs, tittering behind their hands. When the Lobos got out at their floor, Fontaine continued on to her suite on a floor above. “What was all that fuss about?” Lobo asked the girls, putting his newspaper aside when they reached their rooms. “You were being preposterous.”

Ivanhoe

, playing the part of Lady Rowena, opposite Elizabeth Taylor. Unbeknownst to each other, they were staying at the same hotel, Claridge’s. After dinner in the hotel restaurant, Lobo and his two teenage daughters went up to their rooms, Fontaine stepping inside the lift as the doors closed behind them. Lobo took no notice, burying his nose deeper into a newspaper as the bell pinged at each floor. Leonor remembers how she and María Luisa meanwhile elbowed each other in the ribs, tittering behind their hands. When the Lobos got out at their floor, Fontaine continued on to her suite on a floor above. “What was all that fuss about?” Lobo asked the girls, putting his newspaper aside when they reached their rooms. “You were being preposterous.”

Other books

B0042JSO2G EBOK by Minot, Susan

Love Begins with Fate by Owens, Lindsey

Bound to the Bounty Hunter by Hayson Manning

1 The Underhanded Stitch by Marjory Sorrell Rockwell

Scripted by Maya Rock

Argus: Accepting the Challenge by Jana Leigh

Order of the Air Omnibus: Books 1-3 by Melissa Scott

Serendipity by Carly Phillips

Doom Helix by James Axler