The Sugar King of Havana (25 page)

Read The Sugar King of Havana Online

Authors: John Paul Rathbone

Nine

IMPERIAL AFFAIRS

Fortune is a woman and the more she does for me the more I demand from her.

—NAPOLEON BONAPARTE

T

he cartoon says it all. With one hand, Lobo holds above his head a giant globe labeled “The World of Sugar.” He is lithe, almost naked in swimming trunks that are patterned with small dollar signs, and would look like an Atlas were it not for the smoking cigar that hangs from the corner of a rather sour-looking mouth. Conrad Massaguer—noted cartoonist and illustrator, founder of the glossy magazine

Social

, and brother-in-law of Jacobo Lobo’s widow—drew similarly jokey portraits of Cuba’s other sugarcrats. He had sketched Manuel Aspuru, a playboy

hacendado

and friend of Lobo’s, saluting from a paper sailboat in a stylish captain’s uniform. He also executed a Charles Addams–style rendering of Arturo Mañas, head of the Sugar Institute, who looks positively devilish as he ladles another spoonful into an American coffee cup while asking, “More sugar, Sir?” But the Lobo lampoon is the most outlandish of them all. It pokes fun at the virility of a man who drew his inspiration from Napoleon and held the world’s sugar market in the palm of his hand.

he cartoon says it all. With one hand, Lobo holds above his head a giant globe labeled “The World of Sugar.” He is lithe, almost naked in swimming trunks that are patterned with small dollar signs, and would look like an Atlas were it not for the smoking cigar that hangs from the corner of a rather sour-looking mouth. Conrad Massaguer—noted cartoonist and illustrator, founder of the glossy magazine

Social

, and brother-in-law of Jacobo Lobo’s widow—drew similarly jokey portraits of Cuba’s other sugarcrats. He had sketched Manuel Aspuru, a playboy

hacendado

and friend of Lobo’s, saluting from a paper sailboat in a stylish captain’s uniform. He also executed a Charles Addams–style rendering of Arturo Mañas, head of the Sugar Institute, who looks positively devilish as he ladles another spoonful into an American coffee cup while asking, “More sugar, Sir?” But the Lobo lampoon is the most outlandish of them all. It pokes fun at the virility of a man who drew his inspiration from Napoleon and held the world’s sugar market in the palm of his hand.

Lobo as Atlas.

The 1950s marked the zenith of Lobo’s power, although they were uncertain years too, as they were for the Republic. Few Cubans immediately mourned the passing of the corruption of the Grau and Prío presidencies. Yet Batista’s coup did call into question the image that the country had of itself as an “oasis of liberty” in the Caribbean. There was its exalted 1940 constitution, its irresistible sensual pleasures, and its high cultural life. Middle-class Cubans could also boast about the air-conditioners and TV sets that put them on a par with Americans. But now they also had a shabby military dictatorship more worthy of a banana republic than a country aspiring to join the modern world. Chibás’s last message to them had been “Wake Up!” Instead they had remained asleep. The month after the coup,

Time

ran a front-page picture of a smiling Batista with the caption “Cuba’s Batista: he got past Democracy’s sentries.” Although Batista always appeared confident in the capitol, for the next six and a half years there was never a moment when Cuba could be said to be at peace.

Time

ran a front-page picture of a smiling Batista with the caption “Cuba’s Batista: he got past Democracy’s sentries.” Although Batista always appeared confident in the capitol, for the next six and a half years there was never a moment when Cuba could be said to be at peace.

Lobo questioned his life. He reminisced in letters to his daughters about those moments as a carefree student when he had been “completely broke, and I can assure you that these were always the happiest days of my life—perhaps because I had nothing to lose.” It was a remarkable change for a man who had so purposefully pursued fortune all his life, even if Lobo’s new mood was in keeping with the times. In

The Quest for Wealth

, a history of man’s acquisitiveness published in 1956, the economist Robert Heilbroner argued that money-making was no longer generally esteemed due to the experience of the Great Depression. Previous generations had celebrated men who transformed the world. In Cuba there had been sugar barons like Rionda; in the United States, tycoons like Henry Clay Frick with his coal, Cornelius Vanderbilt with his steel and railroads, and Henry Osborne Havemeyer, the “Sultan of Sugar,” with his refining interests on the East Coast. These men lent respectability to their new wealth by buying art, often indiscriminately. “Railroads are the Rembrandts of investment,” Frick once commented, for the value of railways—like that of Rembrandts—always went up.

The Quest for Wealth

, a history of man’s acquisitiveness published in 1956, the economist Robert Heilbroner argued that money-making was no longer generally esteemed due to the experience of the Great Depression. Previous generations had celebrated men who transformed the world. In Cuba there had been sugar barons like Rionda; in the United States, tycoons like Henry Clay Frick with his coal, Cornelius Vanderbilt with his steel and railroads, and Henry Osborne Havemeyer, the “Sultan of Sugar,” with his refining interests on the East Coast. These men lent respectability to their new wealth by buying art, often indiscriminately. “Railroads are the Rembrandts of investment,” Frick once commented, for the value of railways—like that of Rembrandts—always went up.

Such industrialists were no longer flattered and admired. By the 1950s, the archetypal U.S. businessman had become the colorless if reliable figure satirized by Sloan Wilson in his novel

The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit

. The change in style was accompanied by a shift in corporate priorities too, with other motives such as stability, continuity, and responsibility toward the community predominating over the profit motive. “Opulence, the adulation of money-makers, and the wish for great wealth have given way, in part at least, to a new set of values: the camouflage of wealth, the contempt of ‘mere’ money-makers. And even a certain disdain or disinterest in the goal of wealth itself,” Heilbroner wrote.

The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit

. The change in style was accompanied by a shift in corporate priorities too, with other motives such as stability, continuity, and responsibility toward the community predominating over the profit motive. “Opulence, the adulation of money-makers, and the wish for great wealth have given way, in part at least, to a new set of values: the camouflage of wealth, the contempt of ‘mere’ money-makers. And even a certain disdain or disinterest in the goal of wealth itself,” Heilbroner wrote.

In Cuba, a short plane hop from the United States, such attitudes chimed with prevailing social democratic ideals and, increasingly, Lobo’s beliefs too. “Money not only does not bring happiness, sometimes it destroys it, and I sometimes even think it is no less than the devil’s invention,” Lobo wrote to María Luisa in May 1950. “The only way money can bring happiness is if it is used to do good and to help the lot of the less fortunate . . . That’s why I take such a great interest in the problems and well-being of the people at the mills, their education, their health.”

Although sincerely believed, Lobo was not always as disinterested about his wealth or as philanthropic as he sometimes imagined. He continued to reject many of the luxurious fripperies of a Cuban

hacendado

: “I have no yacht.” Nonetheless, the 1950s were also years when Lobo, like the American robber barons of the previous generation, expanded his collection of European art, mostly old masters, haggling with dealers over the price of a Goya self-portrait or a watercolor of Napoleon’s quarters at St. Helena. It was also a decade when Lobo pursued some of his most disruptive and ambitious business schemes. There was certainly a Napoleonic quality about Lobo’s offer to buy the whole Cuban sugar crop in 1952 and again in 1953, as there was in his Napoleon-like womanizing and the size of his Napoleon collection itself.

hacendado

: “I have no yacht.” Nonetheless, the 1950s were also years when Lobo, like the American robber barons of the previous generation, expanded his collection of European art, mostly old masters, haggling with dealers over the price of a Goya self-portrait or a watercolor of Napoleon’s quarters at St. Helena. It was also a decade when Lobo pursued some of his most disruptive and ambitious business schemes. There was certainly a Napoleonic quality about Lobo’s offer to buy the whole Cuban sugar crop in 1952 and again in 1953, as there was in his Napoleon-like womanizing and the size of his Napoleon collection itself.

AS AN ENGLISH SCHOOLBOY, I knew that Napoleon was short, sometimes tucked his right hand inside his tunic, rode a horse, suffered a dreadful retreat from Moscow, and was decisively beaten by British troops led by the Duke of Wellington at Waterloo. Later I absorbed the knowledge that Napoleon ended his life in exile, although for years the thought vaguely persisted that St. Helena was an island somewhere in the Mediterranean instead of deep in the South Atlantic. It was there, in his damp and cramped quarters at Longwood, that Napoleon dictated his memoirs, reinventing himself as a liberal emperor—and one of history’s great victims. “My fame lacked only one thing—misfortune,” Napoleon once said. “I have worn the Imperial Crown of France, Italy’s crown of iron; and now England has given me one that is greater and more glorious still—that worn by the Savior of the World—a crown of thorns.”

There are many Napoleons. There is the lonely Napoleon of high office, and the vicissitudes he suffered in exile. There is the Romantic hero of Balzac and Stendhal, who rose from obscure beginnings to scale great heights. There is the despot, interested only in power, the military hero on a horse, the warlord surrounded by the whiff of grapeshot, who was admired by self-aggrandizing leaders such as Cipriano Castro and later Batista. And there is the empire builder, the man who left behind in France a system of administration and civil reforms that still endures. This is the Napoleon that so many successful businessmen style themselves upon. Thus there have been Napoleons of Steel, of Railroads, of Finance, of Sugar, and even one of Crime.

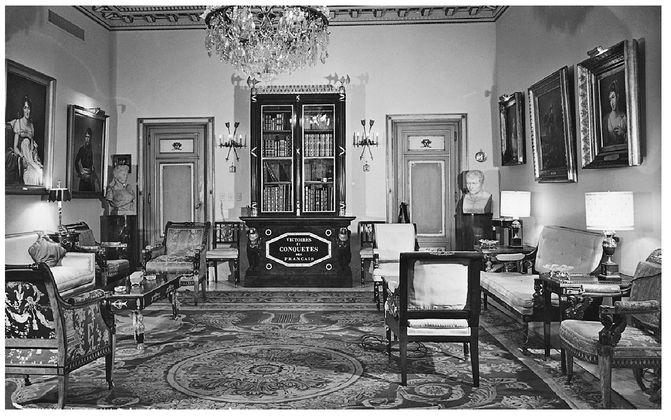

I went to the museum in Havana that now houses most of Lobo’s Napoleon collection. Built in 1928, it is a four-story Florentine-style mansion near the university, built in gray stone. It once belonged to Orestes Ferrara, a Neapolitan-born Cuban politician, and now has the hushed and gloomy feel of a mausoleum. When I visited, the windows’ heavy wooden shutters were closed, and the polished stone floors gleamed with only faint, ambient light. In the lower rooms, there was a sparse collection of sabers, regimental shakos, Napoleon’s “bed pot,” some furniture, and in a glass cabinet one of the emperor’s molars that my mother remembers seeing in Lobo’s house sixty years ago, which caused her to shudder with squeamish delight. More notable objects were on the second floor: in one cabinet, locks of the emperor’s hair; in the corner of a dark room, a bureau that belonged to Napoleon’s minister of police and was used by Lobo as his desk; and in another, the baptismal service with which Napoleon had baptized his son, the king of Rome, and Lobo his first grandchild, Victoria Ryan—although with cane juice rather than water, which he passed over her lips “so that she never forgot the taste.”

Doubtless Lobo saw himself reflected in Napoleon’s character. Unlike some more comic Napoleon enthusiasts, though, he did not reenact old battles with tin soldiers spread over a green baize cloth; nor did he strut around the room wearing one of the emperor’s old hats, as the British diplomat Lord Curzon supposedly did. “An infinite capacity for taking pains,” “an intuitive sense,” “an indomitable will to power,” and “firmness of action” are some of the qualities attributed to the emperor. Compare that with this description of Lobo by Rosario Rexach, the wife of his lawyer León. Lobo, she said, “had an extraordinary ability to create, but to create one has to believe firmly in what one is doing . . . When he embarked on a course of action, he applied all his energies until he achieved it. He went direct to his objective. Often he achieved it. Sometimes he failed. But he had an uncommon courage to accept the consequences of his actions. He never complained when a project failed. And he was always prepared to start again.”

John Loeb, a prominent Wall Street banker who knew Cuba well, once described Lobo as “an unusual man, whose most memorable quality for me was his Napoleon complex. . . . Julio was not the easiest man to deal with.” Yet in an interestingly partial appreciation of his hero, it is significant that Lobo singled out these qualities above all others: “In addition to his abilities as a soldier, statesman, financier, civilizer, organizer, and man of great vision, [Napoleon] was a good son, good brother and good father. . . . He was never cruel with the vanquished, ruthless with the disposed, nor prejudiced with racial minorities.” Lobo once said he wanted his Napoleon collection to be a “laurel to the Emperor,” which alone suggests he saw his collection as a monument of appreciation rather than one of emulation. Like many collectors, Lobo’s need to admire was greater than the need to be admired.

Money is the collector’s usual constraint, and as Lobo’s wealth grew so did the collection. Initially, Lobo stored his Napoleon documents and relics in a haphazard fashion around the house in Miramar. After the divorce from María Esperanza, when he moved back to Eleventh and Fourth streets, the collection expanded until it covered several floors of two of the houses, with Lobo living in a rooftop apartment in the third. By the time of the revolution, it had grown into the largest collection of Napoleonica outside France, with over 200,000 documents and 15,000 objects, managed by a staff of five full-time professional librarians led by an aristocratic bibliophile, María Teresa Freyre. Lobo dispatched his assistants to France for lessons in Napoleonic history, and then to England for the Wellingtonian view. Back in Havana, they used a special cataloguing system commissioned by Lobo and designed by Josy Muller, a curator from Belgium’s Musées Royaux d’Art et d’Histoire. If Lobo wanted to consult a rare document or book, an assistant would bring it to the library, a room exclusively for his own use. Lobo would read in an easy chair, his head tilted into the book, straining in a circle of light, searching among the pages. “It was a sacred place for Julio,” remembered Audrey Mancebo, the library’s second-in-charge. “I often wondered how many of his ideas were born that way.”

Other books

Legal Affairs - Violation: Legal Affairs Serial Romance by Bennett, Sawyer

Darling by Jarkko Sipila

Blame It on Paris by Jennifer Greene

BeautyandtheButch by Paisley Smith

The Mistress's Daughter by A. M. Homes

Beyond The Shadows by Brent Weeks

By Blood Alone by Dietz, William C.

Free Radical by Shamus Young

Good Sensations by S. L. Scott