The Tavernier Stones (23 page)

Read The Tavernier Stones Online

Authors: Stephen Parrish

He thought about calling Sarah. Would she talk to him? Probably not. Besides, Feinstein would answer the phone. That’s how protective he was; he didn’t allow her to answer. No, he couldn’t call, but he needed to find out what kind of progress they were making. Of all people, the one most likely to be in the lead was David Feinstein. If Feinstein won, he’d have both the girl

and

the Ahmadabad Diamond.

and

the Ahmadabad Diamond.

Freeman

. Jesus.

. Jesus.

He seated himself in the tub. After staring at the running water for a moment, he dashed, dripping, into the apartment’s only other room.

“A pen. Where’s a goddamn pen?”

Not finding anything to write with—he spilled the contents of his desk drawers onto the floor—he returned to the bathroom and began marking on the mirror with a bar of soap. Letter by letter, he deciphered the message in the border of Cellarius’s last map, oblivious to the water now overflowing his tub.

TWENTY-ONE

AFTER THE PRESS REVEALED the identity of the pigpen cipher, solutions failed to follow. Since only gibberish resulted from every attempted decipherment, experts concluded the pigpen elements were mere border decorations and urged people to get on with their lives.

Few paid attention. Treasure hunters unhinged by greed showed an uncanny ability to make the facts fit their own random speculations and

a priori

conclusions, proving all claims made by the psychological community about the rationalization powers of the human brain.

a priori

conclusions, proving all claims made by the psychological community about the rationalization powers of the human brain.

In Lausanne, Switzerland, an unemployed carpenter dismantled his vacationing neighbor’s house board by board. When the neighbor returned home to the carnage, the carpenter barely paused while jackhammering the foundation to offer him a cut of the booty.

The entire staff of the U. S. South Pole Science Station resigned en masse and requested immediate transportation to Lisbon, Portugal. And refused to say why.

A submarine commander in the north Atlantic ordered his boat to change course for the Bay of Biscay. When he revealed his theory to the crew, he earned their complete support. However, they had to strap the boat’s first officer to his bunk and spoon-feed him, such was the man’s shortsightedness.

A small crowd of strange people picketed the gates of Fort Knox, Kentucky, convinced the United States’ government had recovered the stones and was hoarding them there. A similar crowd did the same at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in Dayton, Ohio, seeking access to Hangar 18.

Delta Air Lines, responding to popular demand, increased the number of its nonstop flights from all major cities into the Atlanta hub after an article appeared claiming the solution was embedded in the novel

Gone with the Wind

. The article, written by a Delta executive, did not say how. Atlanta hotels filled with tourists who remained in their rooms with curtains drawn and doors latched.

Gone with the Wind

. The article, written by a Delta executive, did not say how. Atlanta hotels filled with tourists who remained in their rooms with curtains drawn and doors latched.

Kommissar Gerd Pfeffer started a pot of coffee, then went to his office window and breathed the morning air. Twenty-one floors beneath him, the honking of car horns and the throaty growl of delivery trucks signaled the beginning of another day in Hamburg.

It was an odd mix of businesses that elected to hang a shingle in full view of police headquarters: the Hallesches Tor, a pub named after a subway station in Berlin. A bakery called Nirgendwo Anders, meaning Nowhere Else, as though the other dozen or so bakeries within walking distance had nothing to offer. The Indonesien, a grocery store that sold, in fact, Indonesian foods. And a pair of prosperous banks that, surprising to no one, had never been robbed.

Pfeffer wondered whether the merchants chose Beim Strohhause because the twenty-two-story Polizeipräsidium was across the street or despite the fact. There was something at once comforting and unsettling about being in the shadow of authority; you either loved it or hated it, and you were never sure which to do at any moment.

The coffee was ready. He sat down at his desk with a pencil and notepad.

First he had to confirm the pigpen cipher was correctly deciphered, and this he spent a few minutes doing. He assumed, like everyone else, the message started in the upper left-hand corner of the map, although for the purposes of code breaking it didn’t matter.

He noticed the cipher could be rendered more difficult in ways that capitalized on its symmetry—by rotating individual elements 180 degrees, for instance. Pfeffer didn’t suspect any such tricks, however. Cellarius hadn’t tried to conceal the existence of his message; it was there for all to see. And he hadn’t gone to great pains to conceal the fact—as the media tacitly assumed—that his Palatinate map was a treasure map. Because he lived in the seventeenth century, a time of simple cryptologic methods, the transpositions and substitutions he employed would probably be straightforward. Or so Pfeffer’s sources had advised him.

The first layer of the puzzle was obviously a variation on the pigpen. Pfeffer hoped and expected there would be only one more layer, and he figured his sources were right: the Vigenère was the most likely candidate.

One of the magazines following the story provided a sharp, close-up photograph of where the original Cellarius map had been torn across its upper right corner. Pfeffer examined the tear carefully with a magnifying glass, trying to determine whether the length of the replacement string—repeated from the beginning of the text—matched the length of the missing string.

Judging from the literature, the existence of the repeating characters was widely known. He wondered, though, whether it would occur to other treasure hunters to lay out their Vigenère keyword accordingly, that is, to start over with the keyword when the repeated string ended. If the number of repeat characters did not

exactly

equal the number of characters missing from the original text, the material following the repetition could be trickier to decipher than the material preceding it.

exactly

equal the number of characters missing from the original text, the material following the repetition could be trickier to decipher than the material preceding it.

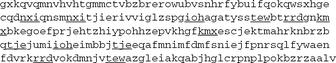

He carefully wrote out the entire code on his notepad, separating and placing parentheses around the repeated string:

Then he wrote out the sliding alphabetic table that powered the Vigenère cipher. The lowercase letters in the body of the table were the cipher letters. The uppercase letters in the column next to the left side were the key letters. And the bold letters in the row along the top generated the plaintext.

Pfeffer poured himself another cup of coffee. It was time to unearth the keyword. If he could discover its

length

, he could get the word itself.

length

, he could get the word itself.

In modern times, the keyword could have been millions of characters long, but in Cellarius’s day, simple words and common expressions served. Probably it was something that had personal meaning to Cellarius or was related somehow to the Palatinate map.

Pfeffer inspected the ciphertext again, after crossing out the duplicate string. He was looking for repeating sequences of cipher letters. He found six sequences of length three—

nxi

,

ioh

,

tew

,

rrd

,

kmx

, and

tje

—and quite a few of length two. He underlined the former in his notebook:

nxi

,

ioh

,

tew

,

rrd

,

kmx

, and

tje

—and quite a few of length two. He underlined the former in his notebook:

He decided to ignore two-letter repeats for the moment, because they were often caused by coincidence rather than a repeat of character strings in the plaintext. The two

nxi

’s were seven spaces apart, measured from the end of the first to the end of the second. Since seven was a prime number—divisible only by one and itself—Pfeffer immediately suspected he had found the length of his keyword. The

rrd

’s were 112 spaces apart, and seven was a factor of 112. Other factors included 2, 4, 8, 14, and 16, however.

nxi

’s were seven spaces apart, measured from the end of the first to the end of the second. Since seven was a prime number—divisible only by one and itself—Pfeffer immediately suspected he had found the length of his keyword. The

rrd

’s were 112 spaces apart, and seven was a factor of 112. Other factors included 2, 4, 8, 14, and 16, however.

It was the

kmx

’s and

tje

’s that threw curve balls: they were 32 and 16 spaces apart, respectively, suggesting a keyword length of 2, 4, 8, or 16.

kmx

’s and

tje

’s that threw curve balls: they were 32 and 16 spaces apart, respectively, suggesting a keyword length of 2, 4, 8, or 16.

Very short keywords were unlikely, because encipherers avoided them. They generated more repeated sequences of letters—more than were evident in the Cellarius ciphertext—and were therefore easier to discover. Pfeffer guessed the keyword was at least six letters long and probably no longer than sixteen, but he was keeping his mind open on the matter.

The two appearances of

ioh

were 80 spaces apart, throwing more doubt on seven as a choice; the only three factors in the range of consideration were 8, 10, and 16. The

tew

’s were 128 spaces apart, also favoring 8 and 16.

ioh

were 80 spaces apart, throwing more doubt on seven as a choice; the only three factors in the range of consideration were 8, 10, and 16. The

tew

’s were 128 spaces apart, also favoring 8 and 16.

He now suspected eight, rather than seven, was the length of the keyword, and he sought to confirm it. If he turned out to be wrong, he would try sixteen next, since it also appeared as a factor in five of the six strings.

Other books

Master Mage by D.W. Jackson

I Married a Bear by A. T. Mitchell

Bond, Stephanie - Body Movers 06.5 by 6 1.2 Body Parts

The Ghost of Valentine Past by Anna J McIntyre

Compulsion by Hope Sullivan McMickle

California Royale by Deborah Smith

Lethal Trajectories by Michael Conley

Dune: The Butlerian Jihad by Brian Herbert, Kevin J. Anderson

Anyplace But Here (Oklahoma Lovers Series Book 5) by Callie Hutton

Rules of Survival (Entangled Embrace) by Jus Accardo