Read The Washington Manual Internship Survival Guide Online

Authors: Thomas M. de Fer,Eric Knoche,Gina Larossa,Heather Sateia

Tags: #Medical, #Internal Medicine

The Washington Manual Internship Survival Guide (13 page)

•

Pain is often an undertreated symptom. In the vast majority of circumstances, acute pain can be treated without compromising diagnostic evaluation or the patient’s clinical condition.

•

Complete absence of pain is often an unrealistic goal.

•

Patients should be frequently reassessed during analgesic treatment.

•

Scheduled analgesics are often more effective than prn administration.

•

For chronic pain, long-acting pain medications can improve adherence and reduce some side effects and can be coupled with immediate-release pain analgesics for breakthrough pain at doses of 5% to 15% of the total daily dose.

•

Avoid IM injections. Subcutaneous opioids are equally efficacious and less painful than IM injections. Uptake can be erratic and unpredictable with both.

•

Before prescribing pain medications, always consider comorbidities, allergies, drug interactions, and potential side effects.

•

Select alternative agents to meperidine, propoxyphene

(no longer FDA-approved in the United States),

and codeine

to limit potential side effects and drug interactions. At least 10% of the US population lacks the appropriate enzyme to convert codeine to the active compound morphine.

•

One should always be aware of the “hidden” acetaminophen in combination products and not exceed the 4 g/d limit (2 g/d in those with liver disease).

•

Consider obtaining a pain management consult for other options in persistent, severe, uncontrolled pain.

•

Trust your instincts. If you think a patient is displaying aberrant drug-related behaviors, set boundaries and stick with them. Questions to ask:

• Does the patient only ask for pain medications when you are in the room?

• Do others observe different behaviors when you leave the room?

• Is the patient “splitting” the staff, playing one against the other?

• Is the patient talking or resting comfortably?

This may be quite misleading in patients with chronic pain and should not be assumed to be a sign of deception in such patients

.

• Is the patient allergic to every pain medication except the one he or she is requesting?

• Is the patient unwilling to accept any adjunctive nonopioid treatment?

• Is the patient very sleepy or lethargic and still asking for more?

EQUIPOTENT ANALGESIC DOSES OF OPIOIDS

Equipotent analgesic doses are approximate

, and clinical conversions should be done carefully.

1.

Calculate the total opioid dose used in the previous 24 hours.

2.

Convert the total dose to an oral morphine equivalent using

Table 16-2

.

3.

Convert from oral morphine equivalent to the new opioid.

4.

Give 50% of the calculated daily dose to account for incomplete cross-tolerance between opioids. Conversion to or from methadone is not as straightforward (see

Table 16-2

).

5.

Schedule the dosing frequency based on the analgesic half-life (e.g., for morphine: q4h, MS Contin: q8-12h; oxycodone: q4h, OxyContin: q12h).

6.

Divide the calculated 24-hour dosage by the number of doses to be given daily.

7.

Add prn doses of the new opioid (short-acting form) at 5% to 15% of the total daily dose for breakthrough pain.

Fluids and Electrolytes

17

BASAL REQUIREMENTS

Water

•

Basal water requirement may be calculated as follows:

• For the first 10 kg of body weight, 4 mL/kg/h PLUS

• For the second 10 kg of body weight, 2 mL/kg/h PLUS

• For remaining weight above 20 kg, 1 mL/kg/h

•

Fever, increased respiratory rate, and sweating can all increase insensible water losses. Insensible losses increase by 100 to 150 mL/d for each degree of body temperature above 37°C.

Electrolytes

•

Sodium: 50 to 150 mmol/d (as NaCl). Most of this is excreted in the urine.

•

Chloride: 50 to 150 mmol/d (as NaCl).

•

Potassium: 20 to 60 mmol/d (as KCl), assuming renal function is normal. Most of this is excreted in the urine.

Carbohydrates

•

Dextrose: 100 to 150 g/d.

•

IV dextrose administration minimizes protein catabolism and prevents ketoacidosis.

MAINTENANCE INTRAVENOUS FLUIDS

•

Basal requirements of water, electrolytes, and carbohydrates can be conveniently administered as 0.45% NaCl in 5% dextrose plus 20 mmol/L KCl.

•

Fluid losses can be divided as urinary losses and all other losses.

• Urinary losses for the average adult are 0.5 to 1 mL/kg/h (e.g., 70 kg person produces approximately 40 to 60 mL/h or 1,200 mL/d).

• Other losses (i.e., water lost in sweat, stool, hydration, insensible losses) total approximately 800 mL/d.

•

For average-sized adults, 2 to 3 L (90 to 125 mL/h) of this IV solution per day is sufficient (i.e., D5½NS + 20 mmol KCl/L @ 100 mL/h).

•

Patients with hypovolemia require more aggressive fluid resuscitation, generally with 0.9% NaCl. Patients with renal failure or CHF may require less.

•

GI and renal losses may significantly increase the loss of water, Na

+

, and K

+

. Serum electrolytes should be followed closely in these situations.

ELECTROLYTE ABNORMALITIES

Hyponatremia

Etiology

•

Hypotonic hyponatremia

is caused by primary water gain or Na

+

loss. Na

+

loss may be the result of renal or extrarenal causes.

•

Hypertonic hyponatremia

is caused by an increase in extracellular solute concentration (e.g., hyperglycemia or IV mannitol administration).

•

Isotonic hyponatremia

(pseudohyponatremia) occurs as a result of a decrease in the aqueous phase of plasma (e.g., hyperproteinemia, hyperlipidemia). The concentration of Na

+

per liter of plasma water is normal.

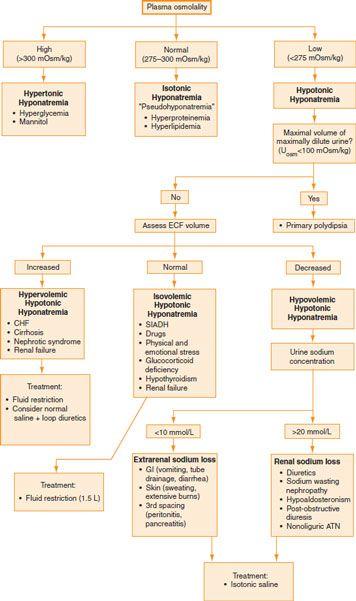

Evaluation

•

A careful H&P should be done, paying close attention to fluid status and the neurologic examination.

•

Plasma osmolality, urine osmolality, and urine [Na

+

] should be measured.

•

Refer

Figure 17-1

.

Treatment

•

Mild asymptomatic hyponatremia generally requires no treatment.

•

For isovolemic and hypervolemic hypotonic hyponatremia, consider fluid restriction.

•

For hypovolemic hypotonic hyponatremia, consider saline therapy

.

•

Careful consideration should be given to the rate of correction of the serum Na

+

.

Too rapid correction may result in osmotic demyelination or central pontine myelinolysis

.

Figure 17-1.

Evaluation of hyponatremia.

• Chronic asymptomatic hyponatremia: Correct slowly, about 5 to 8 mEq/L over 24 hours.

• Severe symptomatic hyponatremia (CNS symptoms): Usually treated with hypertonic saline; however, this must be done with great care and very close monitoring. Aim to correct 1 to 2 mmol/L for 3 to 4 hours; once patient is stable, taper off such that the rise in Na

+

does not exceed 10 to 12 mmol/L over 24 hours.

•

The quantity of Na

+

required to increase the plasma Na

+

by a given amount can be estimated as follows:

Na

+

deficit (mmol) = desired change in [Na

+

] × TBW TBW = 0.6 × body weight (kg)

•

For example, if the desired change in [Na

+

] is 8 mmol in a 70 kg patient, then 336 mmol of Na

+

would be required (42 × 8 = 336). This would be 0.65 L hypertonic (3%) saline (336 mmol ÷ 513 mmol/L) or 2.2 L isotonic (0.9%) saline (336 mmol ÷ 154 mmol/L).

Hypernatremia

Etiology

•

Hypernatremia is caused by Na

+

gain or water deficit (the latter is much more common).

•

Water deficit

caused by decreased intake may be seen in patients with limited access to water (e.g., mental status alteration, intubated patients) or impaired thirst.

•

Water loss

may be the result of renal or extrarenal causes.

•

Rarely, hypernatremia may result from excess Na

+

intake (e.g., hypertonic saline or NaHCO

3

).