The Washington Manual Internship Survival Guide (16 page)

Read The Washington Manual Internship Survival Guide Online

Authors: Thomas M. de Fer,Eric Knoche,Gina Larossa,Heather Sateia

Tags: #Medical, #Internal Medicine

•

In the case of

long R-P tachycardia

consider the diagnoses of 1) sinus tachycardia, 2) atrial tachycardia, or 3) atrial flutter.

•

In the case of

short R-P tachycardia

, consider the diagnosis of 1) AVnRT or 2) AVRT.

•

If the tachyarrhythmia is irregular, the diagnosis is almost always 1) atrial fibrillation, atrial flutter (with variable block) or 2) multifocal atrial tachycardia (MAT).

Sinus Tachycardia

•

Remember, sinus tachycardia is almost

always secondary to another process

.

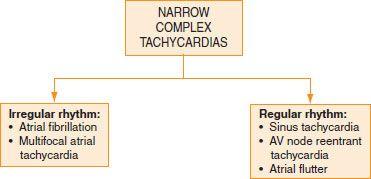

Figure 19-1.

Common narrow-complex tachycardias.

•

In patients with underlying causes for sinus tachycardia such as hypovolemia, pulmonary emboli, or MI, an elevated heart rate may be the patient’s only means for maintaining cardiac output (heart rate × stroke volume = cardiac output), and thus treatment of sinus tachycardia in these patients with negative chronotropic agents (β-blockers, calcium channel blockers) is ill-advised.

•

A thorough workup for underlying causes including those mentioned above as well as infection, anemia, anxiety, exertion, thyroid disease, certain drugs or other substances, autonomic neuropathy (especially of diabetes), and inflammation should be pursued before sinus tachycardia is treated with medications that slow the heart rate.

•

In the patient without heart failure, intravenous fluids aid in the management of most conditions that cause sinus tachycardia and are a useful reflex starting point in management.

•

If telemetric data are available at the onset of the arrhythmia, an examination of a graph of heart rate over time will typically show gradual increase to the fast rate with sinus tachycardia, whereas other NCTs will show abrupt change in rate, signifying the change in rhythm from sinus.

Atrial Fibrillation

•

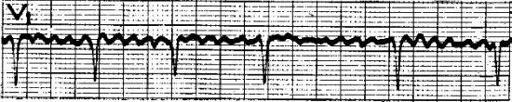

Atrial fibrillation is the result of numerous disorganized foci of depolarization within the atrium and is represented on the standard 12-lead ECG with an irregularly irregular R-R interval and no discernible p-waves (

Figure 19-2

).

Figure 19-2.

Atrial fibrillation.

•

New onset atrial fibrillation and atrial flutter usually have an underlying cause that must be investigated.

•

A convenient mnemonic for common causes of atrial flutter or fibrillation is PIRATES:

P

ulmonary disease,

I

schemia,

R

heumatic or valvular heart disease,

A

nemia,

T

hyrotoxicosis,

E

thanol/

E

lectrolytes,

S

epsis.

•

Because the atrioventricular (AV) node can usually not conduct at a rate greater than 180 bpm, if the ventricular response is at a higher rate, strongly suspect the presence of a coexisting pre-excitation syndrome.

•

Likewise, if the patient in atrial fibrillation on no negative chronotropic agents has a ventricular rate less than 120, strongly suspect node dysfunction. This is important when considering cardioversion.

•

In the hemodynamically stable patient, as you search for the underlying cause of atrial fibrillation, consideration should be given to a rate-control versus rhythm-control strategy, depending on the reversibility of the atrial fibrillation.

•

Rate control is typically achieved with β-blockers and calcium channel blockers, or digoxin

in patients with heart failure and lower blood pressures (see below).

•

Anticoagulation

should also be considered, depending on the patient’s risk of stroke, regardless of whether sinus rhythm can be restored.

•

For new atrial fibrillation of unknown time period, or period greater than 48 hours, care must be taken to avoid cardioversion with pharmacologic or electrical means due to the risk of thromboembolism.

Atrial Flutter

•

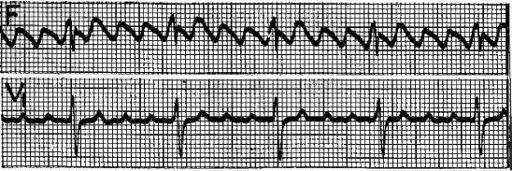

Atrial flutter is the result of large reentrant foci of ectopy within the atria. There are several types of atrial flutter, but the rhythm should be suspected when the atrial rate is around 300 bpm (

Figure 19-3

).

Figure 19-3.

Atrial flutter.

•

Workup and management are identical to those for atrial fibrillation; consideration must be given to rate control, rhythm control, and anticoagulation.

•

Because the AV node cannot usually conduct impulses at a rate greater than 180 bpm, the ventricular rate corresponding to atrial flutter is usually slower and frequently around 150 bpm.

•

One frequent misdiagnosis occurs when the ECG is read as “sinus tachycardia with first-degree heart block” with a ventricular rate of around 150 bpm. If the p-p interval is identical to the r-r interval, strongly suspect atrial flutter with 2:1 block, with half the flutter waves buried within the QRS interval.

Management of Atrial Flutter and Fibrillation

•

Rate control can typically be achieved with calcium channel blockers such as diltiazem, β-blockers such as metoprolol, or digoxin.

•

Diltiazem can be given as an IV push, with a typical initial dose 10 to 15 mg, followed by a continuous infusion, with heart rate and blood pressure parameters communicated to the nursing staff for them to titrate the dose (i.e., please titrate to HR < 100 and SBP > 100).

•

Metoprolol is usually given in increments of 5 mg IV, with up to three consecutive doses at 5-minute intervals, followed by a PO regimen, such as 12.5 mg PO q6h.

•

Digoxin, while also a negative chronotrope, is not an antihypertensive, making it useful for slowing the heart rate in patients with lower blood pressures. Taking caution in patients with renal failure and electrolyte abnormalities, digoxin can be given in increments of 0.25 mg IV q4h. Keep in mind that digoxin will take longer to exert its effect than diltiazem or metoprolol. Ask for help prior to using other agents such as amiodarone, as these confer a risk of cardioversion.

Multifocal Atrial Tachycardia

•

MAT is an irregularly irregular rhythm that is the result of multiple distinct foci of pacemaker activity within the atria.

•

MAT is identified by the presence of three or more distinct p-waves that reliably give rise to QRS complexes.

•

Each p-wave should have a unique morphology and PR interval, owing to their distinct locations in relation to the surface electrocardiographic leads and the AV node.

•

Management does not differ from atrial fibrillation, although the etiology of this rhythm is usually pulmonary in nature

, and anticoagulation need not be considered as patients are not at increased risk for thromboembolism.

AVnRT and AVRT

•

AVnRT (AV-nodal reentrant tachycardia) and AVRT (AV reentry tachycardia) are distinct, pathophysiologically different arrhythmias.

•

AVnRT arises from conduction tissue of differential speed within the AV node.

•

AVRT arises when conduction occurs, often through a muscular bridge, between the atria and ventricles independent of the AV node.

•

AVnRT typically occurs at a rate of around 180 bpm.

•

AVRT can run much faster, owing to the fact that it does not depend on the AV node to sustain its rates.

•

Strongly suspect one of these rhythms when a tachycardia is regular at rates greater than 170 bpm.

•

As always, in the hemodynamically unstable patient, call for help, initiate ACLS if necessary, and prepare for electrical cardioversion!

•

In the hemodynamically stable patient, attempt to make a diagnosis by “breaking the rhythm.”

•

This can be done by first asking the nurse to set up a 12-lead ECG and run a rhythm strip.

•

Initially, ask the patient to perform

vagal maneuvers

(i.e. Valsalva).

•

If this does not work, listen for carotid bruits and if there are none, attempt carotid massage.

•

Never attempt bilateral simultaneous

carotid massage

, for risk of cerebral hypoperfusion!

•

If neither of these produces a satisfactory result, ask for help and have a nurse bring vials of adenosine to the bedside.

•

Adenosine

will block conduction through the AV node, “breaking” AVRT or AVnRT.

•

To administer adenosine, have a nurse place a y-stopcock onto a standard IV. Prepare the patient by telling them they may have an unpleasant sensation upon administration.

•

Always have the defibrillator close by in the event cardioversion or pacing is required.

•

Have the nurse push 6 mg followed immediately by a saline flush, as adenosine will be rapidly metabolized in the arm prior to reaching the heart without a flush.

•

If this does not produce a satisfactory result, try the same maneuver with 12 mg of adenosine.

•

If the adenosine has successfully exerted an effect, but the rhythm is not in fact AVRT or AVnRT, QRS complexes will be suppressed,

and only atrial activity will appear on the rhythm strip. This might aid in the diagnosis of the rhythm, if suppression of the QRS complexes shows flutter waves or a nonsinus p-wave (as in atrial tachycardia).

Atrial Tachycardia

•

A sinus p-wave should be positive in leads II, III, and aVF and negative or biphasic in lead V1, with a PR interval of 120 to 20 ms.

•

If an NCT arises where the morphology of the p-wave is unlike that of a sinus p-wave, the rhythm is atrial tachycardia.

•

It is useful to distinguish atrial tachycardia from sinus tachycardia, as the search for underlying causes will differ.

•

Management of atrial tachycardia is geared toward slowing conduction through the AV node, usually with β-blockers or calcium channel blockers.

Wide-Complex Tachycardias

•

At the beginning of your internship, you should always ask for help before attempting to manage patients with WCT!

•

In the unstable patient with WCT, time to defibrillation is the strongest predictor of good outcomes and survival. As always with an unstable patient, call for help, initiate ACLS protocol, and place defibrillator pads to prepare for electrical cardioversion if necessary.