Tom Brokaw (21 page)

JOHNNIE HOLMES

“It is my country right or wrong. . . . None of us can ever

contribute enough.”

J

OHNNIE HOLMES

was born in Ohio in 1921, but his family moved to the Chicago area after a few years because there was, well, opportunity: an aunt was involved in the Al Capone bootlegging empire and Johnnie's father could get a job as a driver and deliveryman.

They settled in the suburbs, in Evanston, home of Northwestern University, and life was good. His father had steady work and Johnnie, one of the few black students in Evanston High School, has no memory of any racial discrimination.

At an early age he became enthralled with the military way of life. For a time he even considered joining the French Foreign Legion. So by the time the United States was attacked at Pearl Harbor it had a ready volunteer in Johnnie Holmes, even though the U.S. military was hardly friendly territory for black Americans.

It's not that black Americans were not represented numerically. There were 1.2 million in uniform during the war, almost 10 percent of America's black population at the time. Most were confined to the service areas of the military, however. They were ship's stewards or worked in the quartermaster corps or served as drivers for transportation outfits. Ten percent saw combat. Those who did had distinguished records, but the myths remained. The military establishment was reluctant to acknowledge that black Americans were fully capable of taking their place in the front ranks.

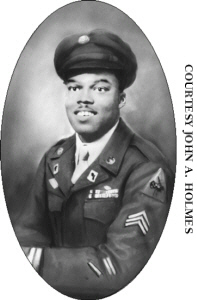

Johnnie Holmes, wartime portrait

Holmes was blissfully unaware of what awaited him. As he put it, “I went into the Army to become a man. I told my momma, âI'm not going to let it break me. I'm going to let it make me.' ”

He began his military career at Fort Custer in Michigan but it wasn't until he shipped out to Fort Knox, Kentucky, that he encountered real, bitter racial hatred and segregation for the first time. All of the noncommissioned officers were white southerners, as Holmes remembers it, and they made the trials of basic training all the more difficult for the all-black outfits. Among other indignities, Holmes is persuaded that Fort Knox dentists experimented on the black soldiers. He remembers being strapped in a dentist chair and getting his teeth drilled with no novocaine.

At the end of basic, Holmes was sent on to Camp Claiborne, Louisiana, to begin his training as a tanker. By now Holmes and the other black soldiers had weekend passes, but even though they wore the uniform of the United States Army and even though they were prepared to give their lives in defense of their country and for the cause of freedom and against the fascist juggernaut rolling across Europe, the racial wounds deepened. Whenever they accidentally strayed into all-white neighborhoods they were met with anger and derision: “Hey, boy, what you doin' here? Git outta here, nigger.”

When a black soldier friend of Holmes's was found dead on railroad tracks near an all-white neighborhood in Alexandria, the other black soldiers were not fooled by the official story that he'd gotten drunk, stumbled onto the tracks, and been run over by a train. They were sure he'd been beaten to death, and they were furious. They were by now combat-trained and they were prepared to go to war against Alexandria. They rounded up their tanks, machine guns, and grenades, but Colonel Steele, their commanding officer, reasoned with them and they backed off.

It wasn't long, however, before there was another racial flare-up, this one at the PX. A black soldier was cheated at the cash register by a white clerk. When the soldier protested, racial slurs started flying, and again the Louisiana base was at a racial flashpoint. Holmes recalls with pride that not long after that the PX staff was integrated.

If anything, life as a black soldier became even more intolerable when Johnnie Holmes and his units transferred to Fort Hood, Texas, to begin the final phase of their preparation as an armored unit. Fort Hood was also home to a stockade full of German prisoners of war. It is one of the little-remembered curiosities of World War II that German and Italian prisoners were often shipped to remote places in the American West to await the end of the war, with more comforts than they would have had at home.

Johnnie Holmes remembers, however, just as Martha Putney remembers. He remembers the German POWs were allowed to go to the PX when Holmes and his friends could not. He remembers white officers saying, “If you boys don't behave we'll have those Germans guard you.” What he remembers most of all was an incident involving his platoon lieutenant, a recent graduate of UCLA, where he had starred in three sports. His name was Jackie Robinson.

One weekend Holmes, Robinson, and some of their friends went to Temple, Texas, on a weekend pass. They weren't in town long before Holmes felt a piercing pain in his chest. He didn't know it at the time but it was pleurisy, an inflammation of the thorax membranes that can be debilitating. He could barely walk.

Lieutenant Robinson helped his young soldier onto a bus headed back to the base, stretching him across the front row of bus seats. The white driver would have none of it, telling Robinson to get Holmes to the back of the bus and get there himself. As Holmes remembers it, Robinson said no, he would not move Holmes to the back of the bus and he sure wasn't going there himself. Holmes recalls that they were arrested by MPs back at the base. I was unable to find references to this in biographies of Jackie Robinson, but given the time and place, it may have been too common to warrant attention.

In many other accounts of his life, another Robinson bus incident involved a light-skinned black woman who was the wife of a fellow officer. When Robinson was told by the bus driver to stop talking to her and move back, Robinson refused and was court-martialed. He was subsequently found not guilty and left the service not long after, suffering from bone chips in his ankle from his college playing days.

Holmes and his fellow black tankers shipped out for Europe as the 761st Tank Battalion. They were quickly in the thick of battle in the final drive across Europe toward the heart of Germany. They were in combat for 183 straight days, including the worst of the Battle of the Bulge, the ferocious fight through the winter of 1944â45 in the forests of Belgium. They were praised by General Patton and the other commanders of the infantry units they were supporting, but they could not fully escape the racial insults, not even there. Holmes remembers coming back from battles, their tanks battered and bloodied by the loss of their comrades, and hearing white soldiers tell Belgian villagers, “Those niggers ain't up there. They're just bringing the tanks up for the white boys to use.”

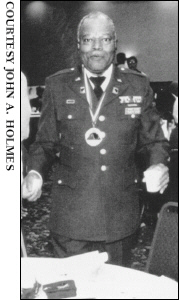

Johnnie Holmes

Johnnie Holmes, with

761

st Tank Battalion

In fact, Holmes and the others in the 761st were face-to-face with death every day. One of Holmes's chilling memories is running through the woods, on attack, when he spotted a German sniper. He opened fire, killing the sniper immediately, realizing that if he had not seen him, just by chance, Holmes would have been shot in the back as he ran past.

There was a widespread belief that the black soldiers weren't up to the job. Dale Wilson, a retired Army major and now a military historian, said, “The African American was fighting a war on two fronts. He was fighting racism at homeâJim Crow, segregationâand he was fighting for the opportunity to fight. . . . Here's a guy who has to beg to get into combat.”

General George S. Patton became a hero to the black tankers when he appeared before the 761st. Holmes thought he was “the most dashing thing you ever sawâstanding on a half-track with those two pearl-handled pistols.” Patton said something to the effect of “You guys are a credit to your race. You're here because I asked for the best. Now go out there and kick some Kraut ass.” Yet there's also evidence that Patton had his private doubts about the ability of blacks to perform as well as whites in the military.

The record of the 761st, however, was exemplary. Those black soldiers earned 8 Silver Stars, 62 Bronze Stars, and 296 Purple Hearts, according to Trezzvant W. Anderson's book

Come Out

Fighting: The Epic Tale of the 761st Tank Battalion, 1942â1945.

The historian Dale Wilson has no doubt about the effectiveness of the 761st. “This unit saw action with eight divisions, so it was making a significant contribution during the war. It performed in an outstanding manner. I think there are clear-cut cases where guys should have been recognized, if not with an award he didn't receive, then with a higher award than what was given.”

Doubts about the fighting ability of the black soldiers were not confined to the American side. Holmes remembers vividly a conversation with a German prisoner of war, a Nazi major who had been born in Chicago before returning to the fatherland. The major, stunned when he saw Holmes, a black man in uniform, said, “What are you doing here? This is a white man's war.”

Holmes and his buddies thought otherwise. They thought it was America's war. One of the veterans of the 761st said more than fifty years later, “When you get over there and the nation's in trouble you ain't got no black and white. You only got America.” A simple and profound declaration from a man who, before he went into combat, trained at bases in American communities where the water fountains and toilets said

WHITES ONLY

.

Holmes's daughter, Anita Berlanga, a Chicago businesswoman, has a different set of sensibilities about discrimination, and she still finds it hard to believe what her father went through. What saddens her most is that racism probably kept him from pursuing a legal career or a career as an artist after the war. As she says, “I learned from my father . . . how ridiculously hypocritical this country is. They took good, honest men and treated them poorly before and after the war.”

They haven't talked about it much but Berlanga says, “I don't know what my father's real expectations were but there was this sense of bafflement: âWhy couldn't I have done that?' The war gave him a sense, for the first time, of what he could do. He was given a job to do and he did it extraordinarily well. Then to come back and find out that didn't countâthat was disappointing, but he kept going. He believed in the essential goodness of man, so coming home to racism was disheartening to him.”

In the rage of combat Holmes often made a deal with God: Get me out of this and I will be a better, decent person. God didn't have to worry about Johnnie Holmes, but he might have spent a little more time with some of the people who were back in Chicago, far from the front lines. One of them was working at the Foot Brothers factory when Holmes went looking for work, now a twenty-five-year-old battle-scarred veteran, down to ninety-eight pounds as a result of lingering problems from injuries suffered when he was hit by shrapnel from land mines. It was Johnnie Holmes's first stop after getting out of uniform. As soon as he entered the office, he remembers vividly to this day, the woman in charge of hiring looked up and said, “What are you doing here? We don't hire niggers. Get outta here.”