Tom Brokaw (25 page)

JOHN AND PEGGY ASSENZIO

“The war helped me love Peggy more, if that's possible.”

J

OHN AND PEGGY ASSENZIO

have been married since a month after Pearl Harbor. He was twenty-three; she was two years younger. They've known each other even longerâsince they were youngsters in Bensonhurst, Brooklyn. Peggy remembers, “When I was eleven, I was on my porch reading. John threw a football to get my attention. I threw it back. That was it.”

Shortly after their marriage, John was heading for basic training at Camp Pickett, Virginia. He was trained as a medical technician and assigned to the 118th Combat Engineers, the men who went in with the first wave to clear the minefields, bust through any defensive barriers, and start a network of roads and bridges for additional troops and supplies. It was vital and dangerous work.

At home, Peggy was a teacher in the Brooklyn Roman Catholic Diocese middle school system during the day and often volunteered at the Red Cross in the evening. She says, “I never went to sleep until I wrote John a letter. I wrote every single day. I wouldn't break the routine, because I thought it would keep him safe. You bet I got to know the men in the post office.” Peggy also followed the progress of John's outfit through the newspaper and kept an elaborate scrapbook of everything connected to his part in the war, including newspaper clippings and his draft notice.

In the Pacific, John was on the move so much he didn't get his mail regularly. He saw action in five different campaigns over twenty-three months. His memories of Okinawa, one of the most ferocious battles of the Pacific war, still come to him in Technicolor. “We were down on our bellies and I saw one guyâhis arm flying through the air; it had been blown off. I jumped up and put a tourniquet on the stump and got him evacuated. I don't know whether he survived.”

John and Peggy Assenzio, wartime

John still breaks down when he recalls one excruciating close encounter. “I was on a scouting mission, crawling, when I came face-to-face with a Japanese soldier. He looked at me and I looked at him. I fired first. He went down. It was a horrible, horrible experience.”

It's all the more important to John that he won the Bronze Star for saving lives, not taking them. On November 12, 1944, at Dulag, on the Leyte Gulf, the Japanese sent a fleet of kamikaze planes to attack U.S. ships anchored in the bay. There were hundreds of casualties. John and another volunteer were on the beach, where they loaded a small boat with medical supplies and rushed out to help the stricken ships and wounded sailors for the next seven hours.

His breaks from combat were rare, so when he arrived in New Guinea there were fifty-eight letters waiting for him, most of them from Peggy. He read them in the order they'd been written, and he remembers to this day that in one of them he learned his grandfather had died. When he had left for basic training, his grandfather had assured him, “You'll come back, but I won't be here,” and then he had kissed John.

What John experienced was characteristic of the personal turmoil in the lives of young people at the time. While the men were in strange and hostile places, thousands of miles from home, relatives died, wives and sweethearts were left to fend for themselves, children were born, and Dear Johns were written. Sometimes it would be weeks or even months before the men would get the news, however disappointing, sad, or joyous.

John's outfit was dispatched to Japan following the surrender. They were assigned to the port city of Kure, just southeast of Hiroshima. He was stunned by what he saw in the ruins of the first target of an atomic bomb. “Hiroshima,” he says, “was the most horrible thing you ever saw . . . just twisted steel, complete devastation.” Assenzio is firmly convinced the decision to drop the bomb was appropriate. Like most veterans of the Pacific, he believes the Japanese would not have given up and there would have been an untold number of casualties during an invasion.

One small moment during John's stay in Japan is a poignant reminder that wars are made from the top down and that the people at the bottom, were it left to them, would likely find other ways to settle whatever differences exist. John says he was under strict orders: “No fraternization with the locals.” But one day he and a friend passed by the home of the postmaster of Kure. He invited them in for tea. “The postmaster could speak English. You should have seen his garden. His little son took out a geography book and pointed to New York, because that's where we were from.

“We had the most delicious teaânever had tea that delicious. We were going against fraternization orders . . . I still had my rifle . . . but they were so nice.”

Days before, the two nations represented by the four people at that party had been in a vicious war with each other. The Japanese family was living in the shadow of the wreckage of Hiroshima, the single most destructive act of war ever. They were entertaining two young Americans, men who were lucky to have survived the deadly intentions of the Japanese as they fought their way across the Pacific. Now they were enjoying each other's company and a pot of wonderful tea.

“I finally got back to New York on December thirtieth. I missed Christmas, but I got a temporary discharge so I could spend New Year's at home. I rode the train into Brooklyn with a rifle over one shoulder and a souvenir samurai sword over the other. I looked so strange.”

When they were courting, John and Peggy had developed a special signal so they could always find each other in crowded places, like Coney Island. It was what John called his “love whistle,” a sweet, melodious whistle in four beats he used only when he wanted to get Peggy's attention. When John arrived at the bottom of the steps leading to her family's home in Bensonhurst on December thirtieth, a great deal had changed in his life, but he remembered how to do the love whistle. When Peggy heard it, he says, “She came running out and almost took my head off.” Her memory: “I had just finished making a big

WELCOME HOME

sign and I was talking to John's uncle when I heard the whistle. I just ran down the steps and hugged him.”

John Assenzio (extreme left) in Kure, Japan

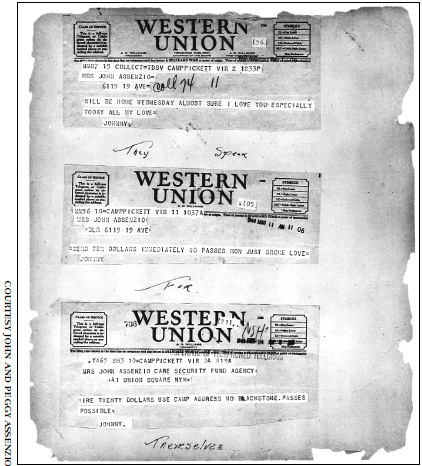

The Assenzios' Western Union telegramsâ“They speak for themselves”

MGM couldn't improve on that for a love scene, and as corny as those black-and-white movies about love and marriage during the war years may seem now, they were a reflection of what was happening to couples across the country. Newly married couples didn't have an opportunity to adjust slowly to the complexities of suddenly sharing a life.

And then they were separated, often for years. Husbands were living in an intensely male environment, trying to deal with the stresses and dangers of war, while young wives were left at home, staying with relatives or living alone in strange cities, working when they could or caring for a child conceived before the father shipped out and born while he was away.

Still, John and Peggy Assenzio were typical. When he came home, they simply resumed their life together. They loved each other. They wanted to have a family. They were faithful Catholics. They were true to the way they had been raised. They were grateful the only lasting effect of the war on John was nightmares. When he went through a difficult time, thrashing around in their bed, sometimes knocking over a table lamp, occasionally sleeping on the floor to avoid hitting Peggy as he flailed out at the dark memories, she was always there to comfort him, to remind him just by her presence that they would get through this together. John says, “The war helped me love Peggy more, if that's possible. To appreciate her more.”

John went back to his old job as a salesman for an import-export firm. Peggy had saved some money from her teaching job during the war. They couldn't find an apartment in their families' neighborhood, so they bought a home on Long Island, thus becoming part of a fundamental alteration of American life, the rise of the suburbs and the subsequent diffusion of the family.

They raised a familyâtwo sons. Their firstborn, John Jr., a schoolteacher, died of cancer a few years ago, and they've established a scholarship in his name. Another son, Rich, is a production manager with NBC Sports.

John and Peggy are proponents of women's liberation, but they worry that in trying to have it allâa career, marriage, and childrenâtoo many young women put their careers ahead of their families. Peggy, who had been a schoolteacher during the war, resumed teaching once the boys were in school themselves. She worries. “The morals have changed tremendously. The way you're told to raise your kids nowâthere's no discipline.”

Divorce is another issue they worry about. Peggy says young couples these days “don't fight long enough. It's too easy to get a divorce. We've had our arguments, but we don't give up. When my friends ask whether I ever considered divorce I remind them of the old saying âWe've thought about killing each other, but divorce? Never.' ”

John and Peggy Assenzio are not unique within their generation. They can look back on a love affair that began in the Great Depression, was consummated at the outset of World War II, survived combat and separation, and flourished in the postwar years. They were just twenty-one and twenty-three when they were married and they could not have imagined what strains the world would put on their commitment to each other, but they believed their wedding vows were not conditional. Now, in their fifty-seventh year of marriage, that belief has not diminished for John and Peggy. If anything, it has been strengthened by John's recurring memories of the horrors of combat. They come to him less often now, but Peggy is always there for him. As he says, “I relive it sometimes, but with the help of my wifeâand the love she has for meâthat's how you get over it.”

These marriages and the values the men and women brought to them may seem curiously old-fashioned to modern young couples. They may have a difficult time relating to a love affair forged by sacrifice and separation, faith and commitment. They may not know how to measure the tensile strength such marriages bring to a society. In an age of divorce, pagers, cell phones, and fax machines, they may never know the sweet sound of a love whistle.